1. The Age of Urban Visions: From Global Cites to Civic Cities

- Hiroyuki Mori, Professor of Economics, Ritsumeikan University (Japan)

Cities and the Capitalist Economy

Human beings have built and resided in cities since ancient times. Cities throughout history have been the “flower of civilization:” they have contained the cutting-edge social resources of their times and have been a driving force shaping the history of humankind.

Most cities were originally created based on political and religious powers around which various social and economic activities were carried out and, ultimately, around which urban societies developed. Cities with a clear identity as a “political city” and “religious city” can still be found all over the world.

In modern times, the market economy itself has become the driving force for the formation and development of cities, and “industrial cities” or “economic cities” are now more common than political or religious ones. In some cases, private industry grew spontaneously, and in others the politically-directed market economy exerted great power. Both types of city growth result from the logic of constant expansion tied to the development of capitalism. Capitalism is an economic system dominated by capital that aims for an eternal process of economic value accumulation that subordinates entrepreneurs and workers. Capitalism pursues constant economic growth for society as a whole, and cities have been the centers of capitalistic economic development. Cities today are developed by the power of this capitalistic economy and have become a base for capital accumulation; land use and public policy are geared toward the purpose of economic growth ().

On the other hand, the accumulation of economic resources in the space of the city has threatened the lives of residents in urban societies. Big companies and high-income earners occupy land that is in good condition and benefits from infrastructure and other social and economic benefits, driving workers to poorer residential areas and suburbs. These workers are forced to live in poor housing and endure bad traffic conditions. Over time, the absence of public health and pollution control eroded their lives and health. Even the supply of social resources such as decent housing and water have been so inadequate that cities were constantly afflicted with fear of infectious diseases and pollution. These issues emerged as a new category of social problems called urban problems. Urban problems emerge at every point in the history of the industrial city. While urban growth under capital accumulation was actively driven by the market economy, the urban policy created to deal with the social costs caused by it was poorly designed and implemented.

The appearance and development of industrial cities continued into the twentieth century. The shift of industrial structure from light industry (e.g., textiles) to heavy industry (e.g., petrochemicals) has led to the development of cities where environmentally destructive industries were concentrated. Environmental problems such as air and water pollution have been extremely damaging to biologically vulnerable populations, such as the elderly and children, and the socially vulnerable, such as those with low incomes. Cities are densely populated and required the presence of social services, public facilities, and infrastructure for residents to be able to live a decent life together.

However, under market-led socio-economic systems, public policies focused on economic growth were prioritized. The municipalities did not actively adopt urban policies from a positive perspective to actively solve the difficulties of living for people, so social movements stepped in to solve urban problems. However, even after these movements, since people in weaker social positions tended to be the victims of urban problems, the enhancement of social services and pollution control measures were frequently neglected.

The growth of the city has also had a significant impact on the natural environment. Natural and agricultural lands in and around the city became the target of development due to their inferior economic value. When municipal power for city planning was weak, the city developed in a chaotic manner, taking on an ugly appearance. These development activities increased the administrative and financial burden on local governments and caused waste in public finance. The unplanned accumulation of business establishments and housing in central areas led to delays in the development of communal social conditions, leading to a shortage of public services such as schools, nurseries, water and sewage systems, and transportation. Residential areas built one after another in the suburbs were often equipped with the necessary infrastructure and social services from the beginning and enormous transportation investments were made to connect them to the central areas. Infrastructure development for disaster prevention also had to be improved in areas where the risk of disasters increased due to business-led land development in both the private and public sectors.

Cities of the Twentieth Century—Developing into Global Cities and Sustainable Cities

Nevertheless, in the decades after World War II, progress in urbanization meant that some of the fruits of high economic growth could be directed to public policies. The three conditions that formed the post-war welfare society were the market economy, the nation state, and democracy, and all worked together. These conditions made it possible to balance urban economic growth and necessary urban policies in a relatively even manner because economic growth increased central governments' and municipalities' tax revenues and allowed them to direct their fiscal resources to the urban policies necessary for the improvement of citizens' lives. In short, within the post-war socioeconomic system, the market economy came under control.

However, cities still faced economic and social problems. Under capitalism, national and local governments had no choice but to adopt public policies premised on economic growth, in which effective urban policies still tended to constantly fall behind. Yet while the rise in respect toward basic human rights during this period advanced urban policy, the change was short-lived.

Welfare states suffered from low economic growth and budget deficits. As a response, so-called neoliberal policies emerged in a search for solutions in the 1980s. Neoliberal economic thought is market fundamentalism, which seeks to entrust the socioeconomic system to market mechanisms as much as possible. The social services and public works projects provided by the central and local governments up to that date were marketized and commodified. Public sector functions were privatized and outsourced to the private sector. Deregulation in the public sector was also carried out to promote this trend, and the natural and social environment of urban and rural areas changed considerably. In the public sector, a type of organizational management that imitated business companies, called new public management (), was introduced, and citizens were treated as customers/objects rather than sovereigns/subjects. Citizens who did not pay a fair amount of tax became bad customers of the public sector, and the safety net for vulnerable groups—who needed the government most—became fragile.

The psycho-cultural impact of the spread of neoliberalism led to a prevalence of extreme individualism and self-responsibility. Under the neoliberal philosophy, deregulation, privatization, and fiscal cutbacks have been promoted since the late 1980s, and the market economy has been separated from political administration and civil society and has taken on a superior position. Moreover, in concert with this, “world cities” or “global cities” such as New York, London, and Tokyo developed as new fields of urban research (; ). The industrial structure of cities has changed drastically, and with the progress of IT, a specialized field called the creative industry expanded significantly (). The development of these new, growing industries have been a major source of economic growth in the twenty-first century, and, when coupled with the deregulation of the labor market, have widened the wealth and income gap ().

This gap has also sharpened social conflict in the city. The city center has been redeveloped to allow for new business activities and to serve the lifestyles of the wealthy. Global money, which has been constantly moving on an international scale, flowed into cities, and urban real estate became the target of global speculative investment. Gentrification expelled the citizens who lived in the city () and has come to be called “urban enclosure” (). As a result, disparities and conflicts have sharpened not only in the economy but also in living conditions among citizens. This change was the logical consequence of economic growth associated with the shrinking function of the public sector. The dominance of the city by the market economy— a constant characteristic of modern history—was advanced to its limit.

In addition, the future of the global environment was jeopardized by the expansion of human economic activity. International environmental problems such as global warming, ozone depletion, acid rain, and marine pollution have become common issues for all humankind.

In response to these realities, deliberative discussions on how a city could best operate have been ongoing since the 1990s. Various opinions on alternative city images include the effort of sustainable cities led by Europeans (). This was an urban movement that responded to the environmental crisis and tried to transform the economic structure of the city into one that was environmentally friendly. This movement was strongly influenced by the idea of sustainable development, which was the philosophy promoted by the report Our Common Future, submitted in 1987 by the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development. Sustainable development places the environment at the center of urban policy.

Unfortunately, the sustainable cities movement during the late twentieth century was based on the premise of maintaining economic growth and demanded that social costs—such as environmental destruction and resource waste—be internalized based on a fair distribution of environmental harm between present and future generations. Due to their economic priorities, sustainable cities had a relatively weak awareness of the other social issues that prevailed in the modern generation.

The Spread of Socio-Pathology and Various Responses in Cities

In the late twentieth century, the world entered the era of neoliberalism in earnest as its influence intensified in cities. Economic globalization, which encouraged the free movement of capital, weakened national borders and caused nation-states to suffer from chronic fiscal pressure. It was the same in cities. This situation prompted a battle among states and cities to attract capital through deregulation and corporate financial support such as tax reductions and subsidies for private companies. At the same time, the role of the public sector was decentralized from the central government to local governments and the private sector.

This battle also meant that people faced lower wages and reduced social services. Inequality widened and poverty intensified, and discrimination against immigrants and certain racial groups increased. In the discussion sustainable cities, however, these conditions were moved to the background. How to deal with growing social conflict caused by reductions to income and social-service disparities has become a major social issue in cities.

As one factor in globalization, cities around the world embraced tourism as an important economic strategy, which in turn caused new social issues. Underlying this trend is the fact that cities have tried to compensate for the shrinking population and economy by developing tourism demand. This is especially true in cities like Kyoto, where tourism resources are abundant while the outflow of working generation is large and birth rate is extremely low. Middle-class and wealthy people from all over the world were rushing to cities in each country as tourists, and hotels and accommodation facilities for tourists were built in order to absorb demand. Traditional commercial stores shifted their aim from residents to tourists. Land and housing prices skyrocketed, a significant portion of existing housing was transformed into facilities for tourists, and some residents were expelled. Chronic problems with infrastructure such as transportation congestion and poor waste treatment occurred, which worsened urban residents' daily lives and aggravated their dissatisfaction. Cities around the world began to seek ways to balance residents' lives with tourism.

In addition, many cities in developed countries began to shrink due to declining population and employment. The most typical situation is found in Japan, which is in the midst of the fastest population decline among all countries, with a population aging more rapidly than any in human history. In particular, Japan has a rigid immigration policy, severely restricting the acceptance of immigrants from abroad, so the population decline has been sharp (). Due to the declining population in Japan, the country’s urban spaces have been compared a sponge, filling with holes as population density has decreased and the problem of vacant houses has become a national social issue. Declining population density negatively impacts administrative and financial efficiency. Many cities in Japan aimed to be compact cities that concentrate people in the city center based on the 2014 amendment of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Urban Renaissance.

A compact city approach like Japan’s causes gentrification because it concentrates administrative and financial resources in the city center. By deregulating land use to encourage compact city formation, the compact city promotes the consolidation of public buildings such as schools and the construction of high-rise condominiums that can accommodate a large number of people. This approach also tends to damage the community and the built environment.

Sustainable cities aimed for environment-friendly urban development. The explosion of the Fukushima nuclear power plants caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011 made the shift to renewable energy an international trend. The normalization of atypical weather has made it clear that climate change is an unavoidable problem, and the number of cities that control greenhouse gases and save energy as much as possible has expanded. Smart cities, which seek to be energy-efficient through IT, are one outcome of this idea. Smart cities are a form of city created by a new industrial structure and initiatives to actively utilize the latest information technology for urban development.

Major efforts have also been made to reduce dependence on the neoliberal free market economy and to create an urban economic structure that is as independent and circular as possible. The guiding idea of the market economy is that the best way to purchase goods and services is to “buy good things as cheaply as possible.” Based on the theory of comparative advantage in economics, it is rational to actively purchase cheap and good products and services from outside the city, and conversely to sell products and services with comparative advantage in the city to the outside. However, the logic of comparative advantage presupposes normal and stable times. In the event of a disaster or other emergency, the socioeconomic structure that presupposes such a division of labor exposes vulnerabilities due to long supply chains.

Therefore, the movement to create a resilient urban economic structure has aimed to increase the economic circulation within the city and diversify its industrial structure in order to construct a community-based or social-solidary economy as promoted worldwide through the “buy local” and “slow food” movements. This represents a reemergence of the idea that the existence of the community should be valued. In addition, it has begun to develop into “municipalism,” extending into a movement that enhances the economic, political, and administrative independence of a city as a whole (; ).

On the other hand, there are still strong movements to develop cities as tools for economic growth. For example, the World Bank seeks to create jobs and mitigate poverty by attracting and growing private firms and industries through the development of more competitive cities (). Cities lead the economy, and so pursuing cities' growth may not be a mistake. However, current cities with their urban problems have emerged as a result of tracking productivity and competitiveness. It is clear from the results of neoliberal urban policies that such competitive cities do not promise to solve the environmental issues and correct the widening disparities among populations. A city’s economic growth should never be denied, but the sound development of a city cannot be directed by the sole value of growth supremacy as it used to be.

Moreover, many recent studies have shown that economic growth and rising incomes are not directly related to people’s well-being. The presence or absence of relatives and friends, health, freedom, the environment, and so forth, do not have a strong correlation with income levels, and it has been reaffirmed that increasing these universal values is an important role of public policy (). Recent disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic clearly show that people’s well-being is based, above all, on safety and freedom from fear. Cities are the most vulnerable to these emergencies, and the promotion of safe cities is emerging as a new policy agenda.

Such new findings provide hope even in the age of shrinking cities. Even if the population and economy shrink, the well-being of the citizens may increase if a high-quality city can be created. To that end, cities that have been developed under the dominance of the market economy must be returned into the hands of politics and society, and new urban policy initiatives must be developed. The diverse urban practices that have spread in the twenty-first century are opportunities to explore new policies.

Toward a New City Vision

The situation outlined so far indicates that the present age is an era in which cities must develop into something new that is not strongly dependent on the single value of economic growth supremacy. The priority must be to develop cities so that people can jointly explore various forms of industry, society, culture, and environment and live happily together.

Notably, a city’s values are diverse and its character will differ accordingly within a certain range of stances toward the public good. This means that we need to create a public discourse space within which people can articulate diverse public values and discuss and consider them carefully.

On the other hand, cities typically have less strong territorial and human ties than rural areas, so individuals are often isolated in them. This characteristic indicates that the operation of a public discourse space is challenging in cities. However, in the present age when neoliberalism has taken hold, regaining the public discourse space in a city is indispensable for creating a new future after a society long governed by market power and directed by the logic of economic efficiency has distorted the meritocracy and neutralized society’s necessarily diverse public and moral discourses (). Since cities with economic supremacy are incompatible with the reality of a healthy society, people must carefully discuss issues based on their diverse public values, and develop a vision for a city that has appropriate systems for politics, economy, and civil society.

Such a vision is not created from a blank slate without a basis in reality. Because development processes repeatedly encounter various trials and errors, this will be reflected in the practices of cities.

As cities have developed along lines determined by economic systems, urban research has also become a central subject of social science. For example, Engels' book on urban problems in the 1870s is a classic analysis of urban problems under industrial capitalism (). On the other hand, social sciences centered on economics have focused their analysis on atomized individuals and companies because they pursued “scientificity.” Individuals and companies are mainly regarded as actors that make up the market, and a model has been built in which the socioeconomic system functions most efficiently when the government sector only responds appropriately to events that occur outside the market. The function of the civil society or community is neglected and viewed as an obstacle to an efficient socioeconomic system.

Karl Polanyi has positioned the market economy, government, and community as the main actors that make up the socioeconomic system, and therefore devised a more comprehensive and realistic model by integrating them (). This framework was developed in economic anthropology and institutional economics and differs from orthodox neoclassical economics. In addition, Polanyi positions human beings as depending on the natural environment and ecosystems and living in institutionalized interactions with them. In that respect, his model depicts a holistic socioeconomic system.

Polanyi models the market economy as a system embedded in society, which he calls “modes of integration.” When applied to cities, such an integrated socioeconomic system is materialized in the most concrete sense. Because the market economy has grown unbalanced in relation to the government and communities, cities have become extremely large and have caused various social pathologies by disrupting proper social integration.

So far, governments have tried to compromise with the market economy, civil society, and the natural environment by curbing it with increasing public spending and enacting public regulations. However, neoliberal globalization has become extreme and put most municipalities under fiscal stress. As a result, the social integration model, by increasing the role of government, has reached its limit. However, many municipalities are promoting marketization, including commercialization in the public sphere, with the aim of maintaining urban society through short-term economic growth. This condition has led to further imbalances between the market economy and political and civil society, as well as increasing disparities and instability in urban societies.

Under these circumstances, Matthew Thomson and others argue for the application of Polanyi's model to a new model of urban governance (). Polanyi attributed the functioning of the economy to provisioning for peoples' needs or livelihood, with the three elements of reciprocity, redistribution, and exchange weaving through mutual processes. Reciprocity means gifting and mutual aid, redistribution means the collection and distribution of economic resources by power, and exchange means the movement of goods in the market. Reciprocity and redistribution belong to non-market areas. Reciprocity is the economic function of community like the management of commons, and redistribution is mainly conducted under the jurisdiction of the government sector. The balance of these three elements varies by time and place and depends on broader social, cultural, political, and economic contexts. Currently, market exchange is the dominant process in cities. Thomson and others insist that modern municipalities should properly reintegrate Polanyi’s three economic elements with urban economies using political, legal, and economic powers to create social justice and sustainable economic development. In that case, it is crucial to make full use of fiscal tools and public regulation, create public value, and revitalize the community beyond the logic of capital.

The dominant actors in Polanyi's three economic elements each have their own codes of conduct, as shown in Table 1.1. The codes of government and the market are widely understood in theory and practice. However, the code of conduct for a community may differ depending on the understanding of the basis of the community’s existence. For example, if community is understood as a mere collection of individuals, as it is in mainstream social sciences, the idea of inclusiveness does not appear as part of its code of conduct. However, if companionship implied in reciprocity or mutual care is understood as a part of human nature that transcends individual profit and loss calculation and coercion, then “inclusiveness” is nothing but the original function of community. In this sense, the community code of conduct can be defined by inclusiveness. As the expansion of the market economy and the cutbacks by the government have caused the decline of urban society, the fate of the city in the future depends on how community can be activated through this function of inclusiveness.

Table 1.1: Logics of community, government, and market

| Economic role | Code of conduct | |

|---|---|---|

| Community | Reciprocity | Inclusiveness |

| Government | Redistribution | Fairness |

| Market | Exchange | Efficiency |

Source: Author

In order for a community to have strong inclusiveness, it needs to rely on a social philosophy (or communal value); some examples include autonomy, mutual respect, symbiosis, solidarity, self-esteem, empowerment, and democracy. The socioeconomic system that embodies these qualities holistically can be said to have public value. Community is an element of the nature of human society that has been passed down from the origin of human beings' group life, and is the most important viewpoint through which we can revive cities as a space where we live.

Municipalities should move toward becoming sustainable cities in the future by actively creating socioeconomic structures with this public value. For that purpose, it is crucial that the policy of community strengthening in the municipalities, which has been weakly grounded in theory and practice, is more fully developed.

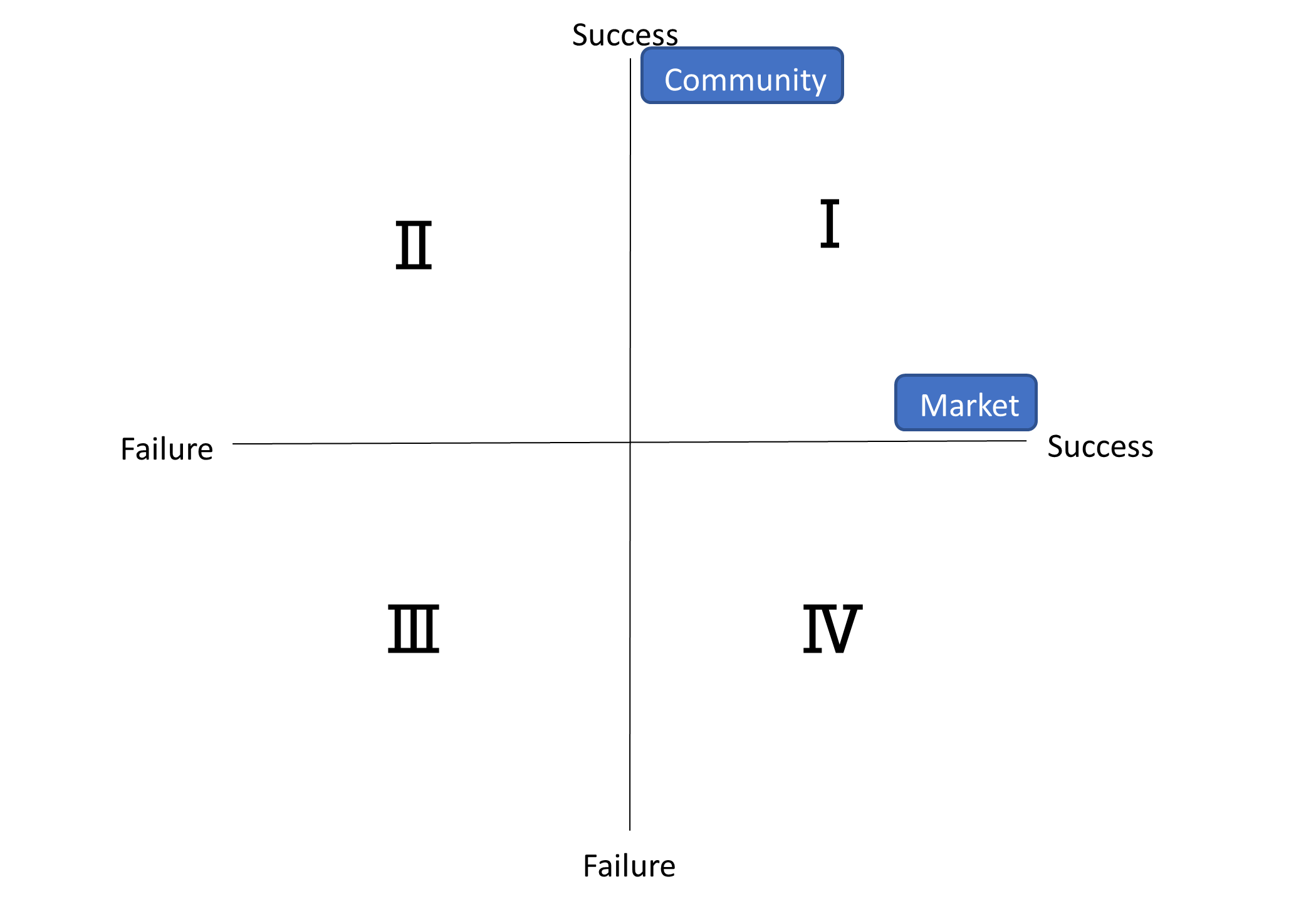

Fig. 1.1 distributes public policy implemented by municipalities across four quadrants showing the success or failure of policies in terms of community and market effects. In mainstream social science (especially economics) so far, only market successes and failures have formed the basis of public policy. Public goods provision, redistribution, and economic stabilization have also been regarded as the role of public policy by the government, but none have been considered to have a direct relationship with the community. Therefore, for example, public assistance that has lacked a sense of community value sometimes caused emotional conflict between residents. Future urban policies must aim for the development of new cities by pursuing a model in which both the community and the market economy are encouraged to develop (the area depicted in the first quadrant in Fig. 1.1). For example, urban industrial policies that utilize labor and economic resources within a city are put in the first quadrant area. This kind of policy will give the residents involved a strong awareness of their interdependence and strengthen social credibility and ties. This policy will also increase the community’s trust in local governments and businesses.

Fostering such a strong sense of trust in civil society is also important for the efforts of smart cities, which will have to progress rapidly in the future. Collecting and utilizing data on people's behavior won’t be possible without their willingness to trust in information management and utilization by governments and businesses. Smartening without such trust violates people’s privacy and deprives them of their freedom. In this case, smart cities become surveillance societies based on data controlled by governments and businesses. Surveillance is never acceptable in a society based on modern democracy.

In this book, we will discuss new methods of urban governance derived from each field as a platform of community perspective including sustainability.

Book Structure

This book sets out to explore the future of the city at the contemporary turning point in the neoliberal era from the viewpoint of public value. Public value is an obscure and dynamic idea, but that does not mean it is less important in science. Rather, it can be said that as a result of the spread of "scientific" economic activities and administrative policies in a narrow sense, the forms of community that underpin human existence have been weakened, leading to social, cultural, and environmental deterioration. Current public value should be based on the human rights of individuals and on restoring the nature of the community and environment. To help readers navigate the rest of the book, we have provided the following summary of the chapter contents.

Part I: The Age of City Regeneration (Chapters 1 and 2) gives an overview of the current situation at which the global market, led by neoliberalism, has arrived from the perspective of cities. The market has reconstructed the foundation of public value in its interest, yet it is indispensable for future city regeneration. Public value is essential for the establishment of a city based on community or civil society, which prioritizes the fellowship of its citizens. Public value is not a clear-cut idea, but it is very important to recognize that a constant orientation of citizens towards public value will promote a permanent movement for the creation of a good city and society.

Part II: New Urban Visions picks up typical directions for new urban development in the cities of the present based on the perspectives developed in Part I. Urban restructuring that employs rapidly advancing IT is an initiative that has obviously enabled the introduction of smart cities. Chapter 3 discusses the features of the smart city and suggests new directions to be taken for IT to be utilized in urban life.

Chapter 4 explores the situation surrounding shrinking cities in Japan and discusses measures for their revitalization based on the shared conditions of cities in developed countries where the populations are also declining. The chapter suggests that, even if the city shrinks in size, this is not directly related to citizens' well-being and the city’s livability. Rather, the autonomous policy capacity of the municipalities and citizens is crucial to determining how to create a livable city in the face of population decline.

Chapter 5 discusses the challenges of restoring and retaining the qualities of natural ecosystems that have deteriorated due to urbanization. From a purely economic perspective, it is desirable for cities to concentrate their economic and social resources on growing their economies as much as possible. From this perspective, natural ecosystems have long been treated as irrelevant to the market economy and evaluated only when valuable as “resources.” Their intrinsic value has been treated as ancillary. In this chapter, new city efforts to restore them are discussed.

Chapter 6 explores urban practices that can positively impact various vulnerable or marginalized people and support their self-esteem and social reinstatement. Neoliberalism has created a significant number of vulnerable groups in cities around the world. Financial disparity and discrimination are based on a false meritocracy developed in the name of personal responsibility. However, human conscience and an innate community spirit prevents us from leaving such socially vulnerable people behind. Attempts are being made to walk hand-in-hand with them as citizens sharing the same city.

Chapter 7 discusses how to create an inclusive city that encourages participation by marginalized people. It can be said that this is important to the restoration of a true civil society, which is the key to true urban regeneration in the future. In this chapter, the best practices for and primary challenges of achieving this purpose are presented.

In the spirit of implementing the proposals in Chapter 7, the critical points for putting them into actual practice are specifically examined in Part III: Strategies for Inclusive City Making. Chapter 8 examines the reality of gentrification, which is a spatial expression of people’s conflicts in cities, and discusses countermeasures. Gentrification is not a simple matter of people being segregated according to their income disparity, but steadily unfolds through the effects of various economic and social factors such as tourism. This chapter discusses these factors from a comprehensive perspective.

Chapter 9 examines a practical strategy for regenerating the community. Community revitalization and strengthening includes a wide range of activities, from soft practices that directly restore people’s connections to hard developments in built environments that naturally create networks of people. Without such integration, a community strategy cannot be fully functional.

Building on this point of view, Chapter 10 discusses the practical regeneration of the community centered around the development of a concrete architectural space conceived from the standpoint of the vulnerable. It is clear from the cases introduced in this chapter why the strategy for creating community from both software and hardware is important. This chapter shows that future community regeneration must be promoted by a strategy that integrates them both.

In Chapter 11, we discuss how to utilize IT, which will expand rapidly in the future, for urban planning that supports community regeneration and strengthening. This planning proposes the ideal state of smart cities from the perspective of community strategy, and this chapter explains how important IT is for the development of cities that serve a purpose beyond mere technological progress.

City visions and efforts in the above chapters encourage reflection on the state of the capitalist economy itself, which is the driving force behind the creation, development, and decline of cities. Part IV: Cities and Capitalism deals with this subject head-on. Chapter 12 argues that urban theories and policies that do not fully reflect the capitalist nature of the economy are ineffective in today’s era of social change. It imagines a future city that incorporates all these points, the ideal form of which will vary depending on its location and conditions. Even within each country or region, cities make a difference depending on how they utilize their autonomy. With this premise in mind, we must develop the city as a spatial property common to all humankind.

Chapter 13, the book’s conclusion, re-proposes the citizen-centric principle by placing public value, a topic that runs through this book, as the foundation of the future city and the basis of urban governance.

Bibliography

- Baird, K.S. et al., 2019

- Baird, K. S., Junque, M., & Bookchin, D. (2019). Fearless Cities: A Guide to the Global Municipalist Movement. New Internationalist.

- Engels, 2021

- Engels, F. (2021). The Housing Question, New York: International Publishers.

- Expert Group on the Urban Environment, 1996

- Expert Group on the Urban Environment (1996). European Sustainable Cities Final Report. European Communities.

- Florida, 2002

- Florida, R. (2002). The Rise of the Creative Class. Perseus Book Group. - id: “Friedmann 1986”

- Friedmann, 1986

- Friedmann, J. (1986). The World City Hypothesis. Development and Change, 17(1), 69-83.

- Harvey, 1985

- Harvey, D. (1985). The Urbanization of Capital. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hodkinson, 2012

- Hodkinson, S. (2012). The New Urban Enclosures. City, 16(5), 500-518.

- Hollander, 2018

- Hollander, J. B. (2018). A Research Agenda for Shrinking Cities. Edward Elgar.

- Hood, 1991

- Hood, C. (1991). A Public Management for All Seasons?. Public Administration, 69(Spring), 3-19

- Polanyi, 1944

- Polanyi, K. (1944). The Great Transformation. Beacon Press.

- Sandel, 2020

- Sandel, M. J. (2020). The Tyranny of Merit. Allen Lane.

- Sassen, 1991

- Sassen, S. (1991). The Global City: New York, London. Tokyo. Princeton University Press.

- Smith & Williams, 1986

- Smith, N., & Williams, P. (1986). Gentrification of the City. Allen & Unwin.

- Thomson, M. et al., 2020

- Thomson, M., Nowak, V., Southern, A., Davies, J., & Furmedge, P. (2020). Re-grounding the City with Polanyi: From Urban Entrepreneurialism to Entrepreneurial Municipalism. Economy and Space, 52(6), 1171–1194.

- United Nations, 2020

- United Nations. (2020). The World Happiness Report 2020.

- World Bank, 2015

- World Bank. (2015). Competitive Cities for Jobs and Growth.