10. Single-Mother Shared Housing as Space for Inclusion

- Lisa Kuzunishi, Associate Professor, Faculty of Regional Development Studies, Otemon Gakuin University (Japan)

Women in Poverty and Reduced Marriage Rates

The phrase “women in poverty” has gained increasing attention as a term referring to unmarried women among the working poor.

In 2011, the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (IPSS) released shocking data showing that effectively one in three unmarried women living alone is living in poverty. Consequently, special reports on women’s poverty frequently surfaced in the media. Women in this position are at the bottom of the social ladder, working multiple low-wage jobs with little time to sleep and having to cut down on utilities and food costs. Many women across social classes appear to feel a kinship with them, based on the powerful response to an NHK program (Nippon Hoso Kyokai; Japan Broadcasting Corporation) on the subject from 2014. In 2017, the Yokohama City Council for the Promotion of Gender Equality released the results of a full-scale survey of situations faced by these women, leading to, among other things, discussions specifically geared toward producing a better understand of the factors that produce women’s poverty, as well as providing methods for support.

However, women have always had to deal with poverty. The statistics indicate that women’s employment rates have increased in the last thirty years, and the M-curve that shows Japanese women’s labor force participation rate is flattening due to the rising rate of women working all their lives. Why, then, is the issue of women in poverty coming to the fore only now? One major factor in this new attention is the increase in unmarried and divorced women. That is, the “safety net” of marriage, previously a lifetime guarantee for women, is no longer functioning as advertised, which exposes women’s poverty.

Single-mother households have conspicuously high poverty rates even relative to the number of women in poverty in general. According to the 2019 Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions, the poverty rate for single parents was 48.1%; about half of all single-parent households were in poverty.

According to a 2017 survey by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW), the employment rate among single mother households in Japan is 81.8%, high even in comparison with other countries, and many single mothers are unstably employed. Therefore, the mean earned income of single-mother households is two million yen; even with welfare payments included, it remains extremely low at 2.43 million yen. Estimates within the same survey find a total of 1.23 million single-mother households, of which 80% are the result of divorce. As lifestyles have become diversified, society has come to accept that leaving a marriage and taking the children is one possible choice that women can make when living their lives. It is a very welcome development that women are now able to choose their own paths in life without being caged by concerns about appearances or outdated customs. However, single-mother households in Japan face the reality that, in return for this freedom of choice, they are now forced to accept the risk of poverty.

Single-Mother Households and Housing Loss

Decreasing marriage rates are also impacting the area of housing. In the earlier era of homogeneous life courses, people formed so-called “standard” families and worked to own homes, climbing the housing ladder as a single unit. The owners of those houses were, almost without exception, the men/husbands, whereas the women/wives had only to buy into the system called marriage to acquire stable housing. However, with the shelter guarantee system called marriage now collapsing, a sharply increasing number of women are forced to obtain housing through their own efforts. In Japan, with its insufficient supply of public housing, residential quality directly reflects payment capacity. Consequently, the housing available to women in poverty is by definition low quality.

Single-mother households are often characterized by the loss of housing following a divorce. There are various reasons why this occurs. When moving out of a family-owned house, divorced women may give reasons like “it was in my husband’s name” and “I was worried about staying in a house where the loan wasn’t paid off,” whereas for housing rented during marriage, the reason might be “moving to a place with cheaper rent.” Furthermore, many women also leave their homes due to issues such as domestic violence (DV) or debts ().

At a time of pronounced financial instability in the aftermath of a divorce, finding a new place to live and moving there with small children in tow can be immensely difficult. In many cases, women find that having left their homes, they have nowhere else to go and have to wander the streets.

Even if they apply to real estate agents to find private-sector rented housing, they are likely to be unwelcome to landlords because of their unstable income. The MHLW survey of 2017 mentioned above found that while over 70% of single mothers had been employed when the mother was married, only 30% of them had been full-time company employees. From the perspective of real estate, housewives and part-time pink-collar workers are inevitably high-risk with regard to rent arrears. Some are able to move in with parents or relatives, but not everyone has this option. There are a significant number of women and children exposed to the risk of housing loss at a level that is impossible to quantify.

Insufficient Public Housing Support

Welfare exists as a system to support households struggling with poverty and facing housing loss; however, only 11.2% of all single-mother households receive welfare support (). Clearly, this number is absurdly low in comparison with their high poverty rates. Therefore, it is easy to conclude that many households cannot or do not receive welfare even though they are qualified for it. Moreover, the media have also reported on the dismissive treatment meted out at welfare consultations. Additionally, according to Yoshitake (), “there is a tendency to not seek welfare among single-mother households ‘close to independence,’ those where the mother is relatively well-educated, employed, in reasonable health, with strong self-discipline, and inclined to value ‘independence and self-help.'” According to Yoshitake (), a tendency toward strong self-discipline is a mechanism which involves highly valuing “independence and self-help” and refusing to receive welfare. This refers to the perception or attitude that hard work will make hopes and dreams come true. This background factor may be significantly influenced by the social stigma against welfare recipients.

Meanwhile, facilities available to mothers and children with no place to go include maternal and child living support facilities. After World War II, when war widows were prevalent, these facilities functioned as important housing options for mothers and children—there were approximately 600 throughout Japan. However, facility residents numbers decreased as time passed; as of a 2018 survey, there were only 222 facilities extant (). Reasons noted for the decline in usage include a mismatch with modern clients’ needs (curfews and other rules), dislike of the implications of the “facility” name, and so on.

Finally, public housing exists as a housing support option for single-mother households. Public housing was established as a measure to combat the postwar housing shortage and, in particular, to guarantee housing for those with low incomes, through the 1951 Act on Public Housing. However, there are merely 1.92 million public housing units throughout the country, that is, about 3.6% of the entire housing stock, which leads to supply issues. Further, housing estates with vacant units tend to cluster in inconvenient suburban areas, causing serious problems with uneven geographical distribution. In addition, an issue particular to single-mother households is the lag between applications for public housing and the preferred entrance period, which creates timing issues that prevent entry. While some municipalities accept applications during divorce disputes, applicants are required to cancel their applications if their divorces are not complete by the time of entry (excluding urgent situations such as DV). In particular, the poverty of “pre-single mothers” (pre-divorce single mothers) has been identified in recent years. Forced to live as single-mother households for all intents and purposes, a significant number of households are barred from any and all public support for single-mother households because their divorces are incomplete. Not all dissolutions of marriage go smoothly, and it is not unusual for divorce to be preceded by a long period of separation. Notwithstanding the severe housing needs that arise during this gray area between marriage and divorce, the worst problem here is that there are no housing policies offering support.

The Emergence of Single-Mother Shared Housing

One potential way to fill these gaps in the system is single-mother shared housing (SMSH). Remarkably, these programs are nearly all corporate, that is, established by real estate agencies. Conventionally, low-income single-mother households have been excluded from the housing market. However, in recent years, to address the worsening issue of vacant houses, more agencies are supplying housing to single mothers.

Having experienced severe housing shortages due to war damage, Japan promoted a housing supply system based on three pillars—the Government Housing Loan Corporation, public housing, and Housing Corporation semi-public housing—with housing units exceeding the number of households by 1968. Thereafte, large-scale housing construction (mainly by private-sector developers) continued as well. From 2008 onward, the population began to decrease as society aged, and the birthrate fell; thus, more houses became vacant. In 2018, there were 8.46 million vacant houses, approximately 13.6% of the total housing units, the highest percentage since WWII ().

As noted above, renting to economically unstable single-mothers carries with it the risk of payment arrears and potential damage to the operating company. However, the dilemma is that if companies follow conventional practices by targeting only those with stable incomes, they will not fill their vacant units. From the late 2000s onward, then, the strata of society with low incomes, including the single-mother households previously excluded from the housing market, were more likely to be included in accordance with risk mitigation frameworks. SMSH can be understood as one aspect of this movement.

As of September 2021, there are 40 shared houses for single-mother households in Japan. Many of them do not require the down payments or guarantors typical of ordinary rental housing, and some permit entry to unemployed people following pre-entry discussions. However, almost all are based on short- and fixed-term rental contracts, whereas those admitting unemployed people take risk-avoidance measures such as advance rent payment or savings confirmation ().

Shared housing refers, essentially, to multiple unrelated households sharing the same residential unit. Ninety percent of existing SMSH involves sharing bathrooms; there are just a few newly built units with separate bathrooms for each household. The rent ranges from 25,000 to 150,000 yen, which notably covers a wide range not limited to low-income families ().

Independence for single mothers is characteristically delayed and hampered by the following four issues: (a) housing is difficult to find without employment; (b) jobs are difficult to find without a fixed address; (c) jobs are difficult to find without childcare; and (d) childcare is difficult to obtain without an employment certificate, which requires a job.

To resolve these issues within SMSH, some houses offer childcare, provide employment opportunities or places to work, and generally provide all-in-one support for mother-and-child independence.

However, housing projects targeting those with low incomes make minimal profit and are often closed or repurposed. Issues said to arise within SMSH include rent arrears, conflicts between residents, child neglect, and so on, with a wide range of care required including welfare services, medicine, and overall health (e.g., DV, poverty, disability, and mental illness) services. However, many of the businesses involved lack knowledge of the welfare system when they begin the project, which makes providing suitable support difficult.

To find smooth resolutions for the problems common to these businesses around the country, a Nonprofit Organization (NPO) called the National Single Parent Residential Support Council (NSPRSC) was founded in 2019. As well as providing system information and advice to its members, the Council also operates a dedicated portal site for SMSH and provides other support for appropriate operations.

The Needs of Single-Mother Shared Housing

What are the needs of single-mother households taken on by SMSH? Here, let us examine the trends in SMSH needs based on inquiry data obtained from Mother Support, the aforementioned portal site operated by the NSPRSC.

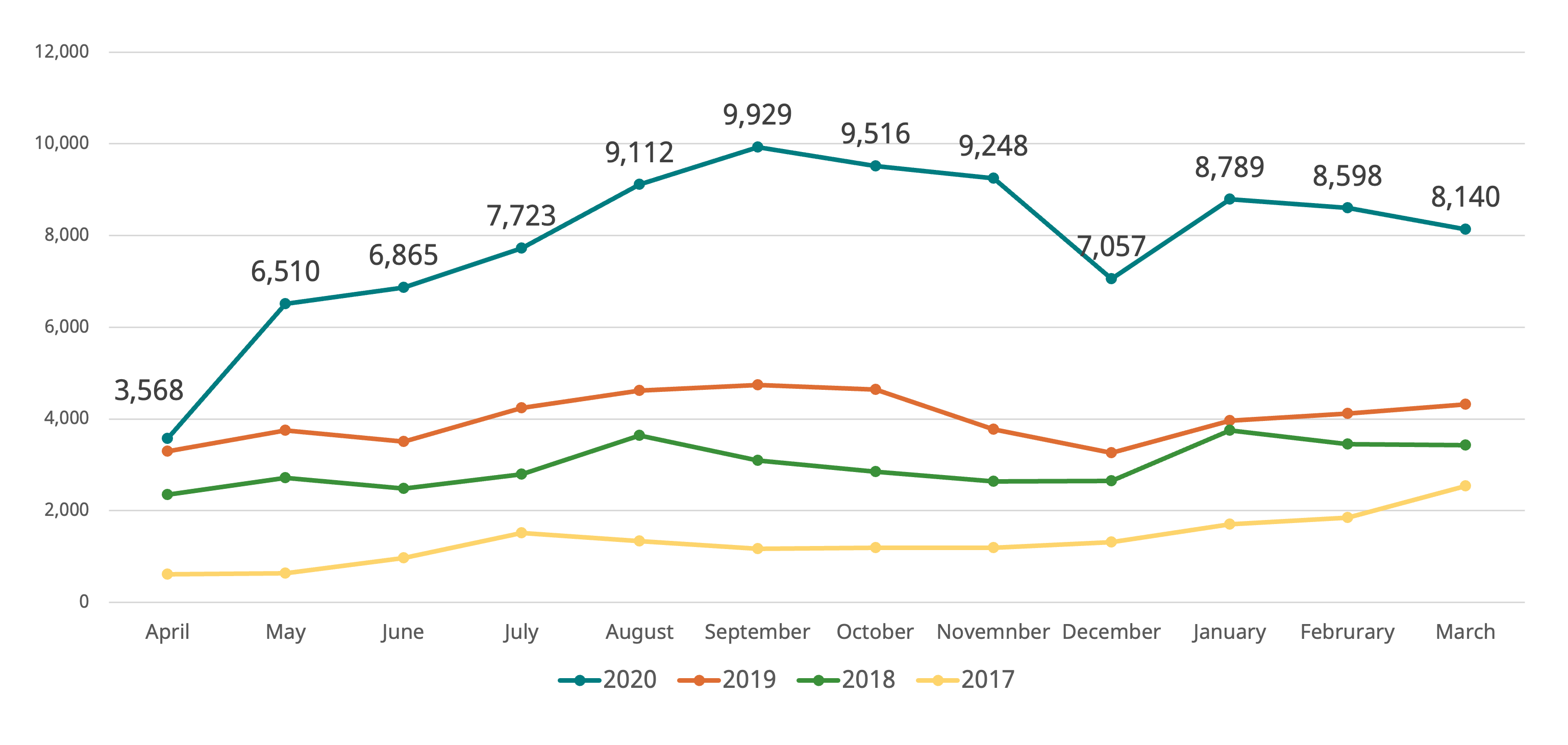

Mother Support was founded as an individual endeavor by Satoshi Akiyama in 2015 and passed on to the NSPRSC from 2019 onward. Access to the site steadily rose from 2017 through 2020, with a sharp increase beginning in April 2020 when a state of emergency was declared due to the coronavirus pandemic (Fig. 10.1).

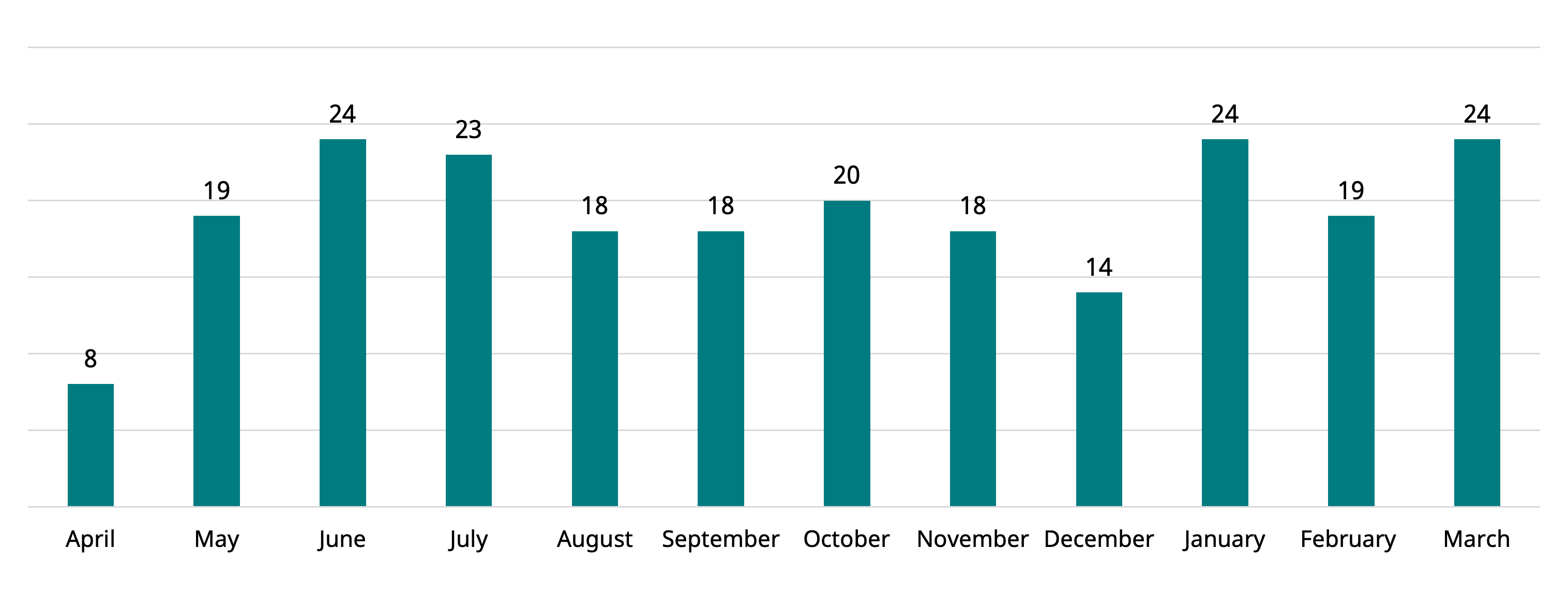

This paper analyzes the 229 requests for on-site support made from April 1, 2020 through March 31, 2021 (Fig. 10.2). From April 2020 onward, new inquiry items intended to facilitate the smooth matching of the person making an inquiry with businesses included questions on (a) marital status, (b) employment status, (c) desired entrance period, (d) age of mother, (e) number and gender of children, and (f) current address and desired house location. These categories were established to reflect requests from NPO members.

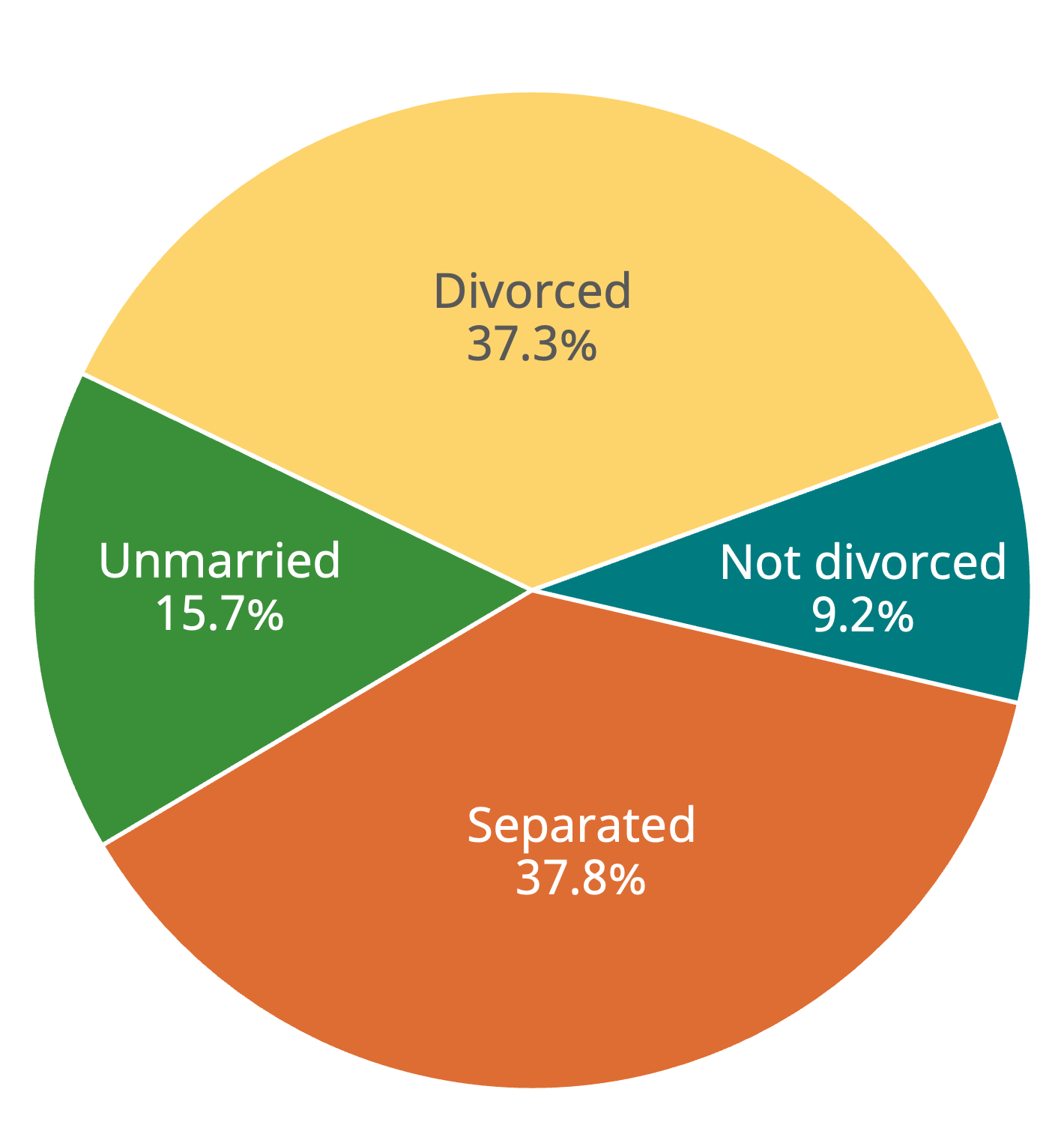

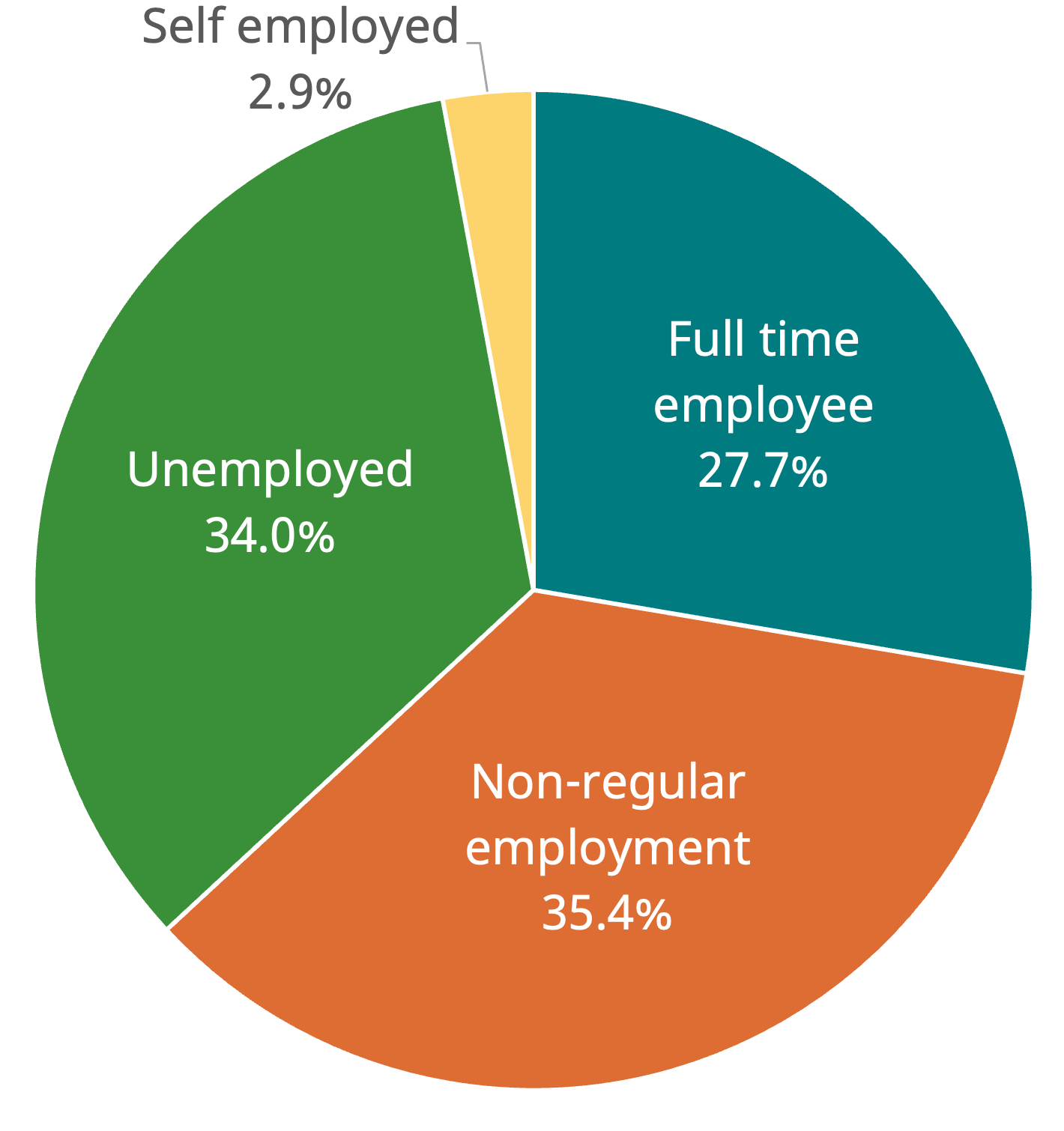

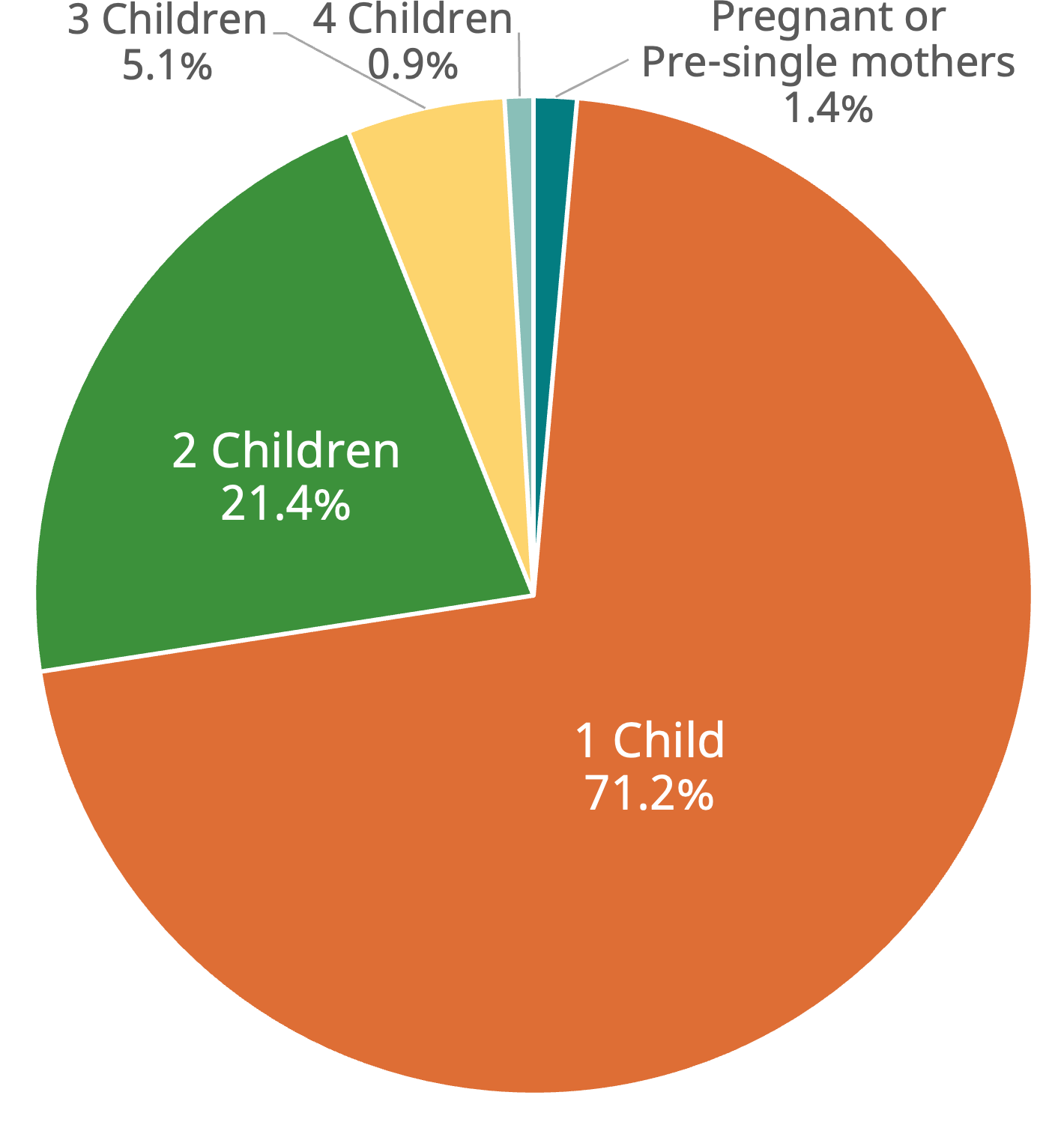

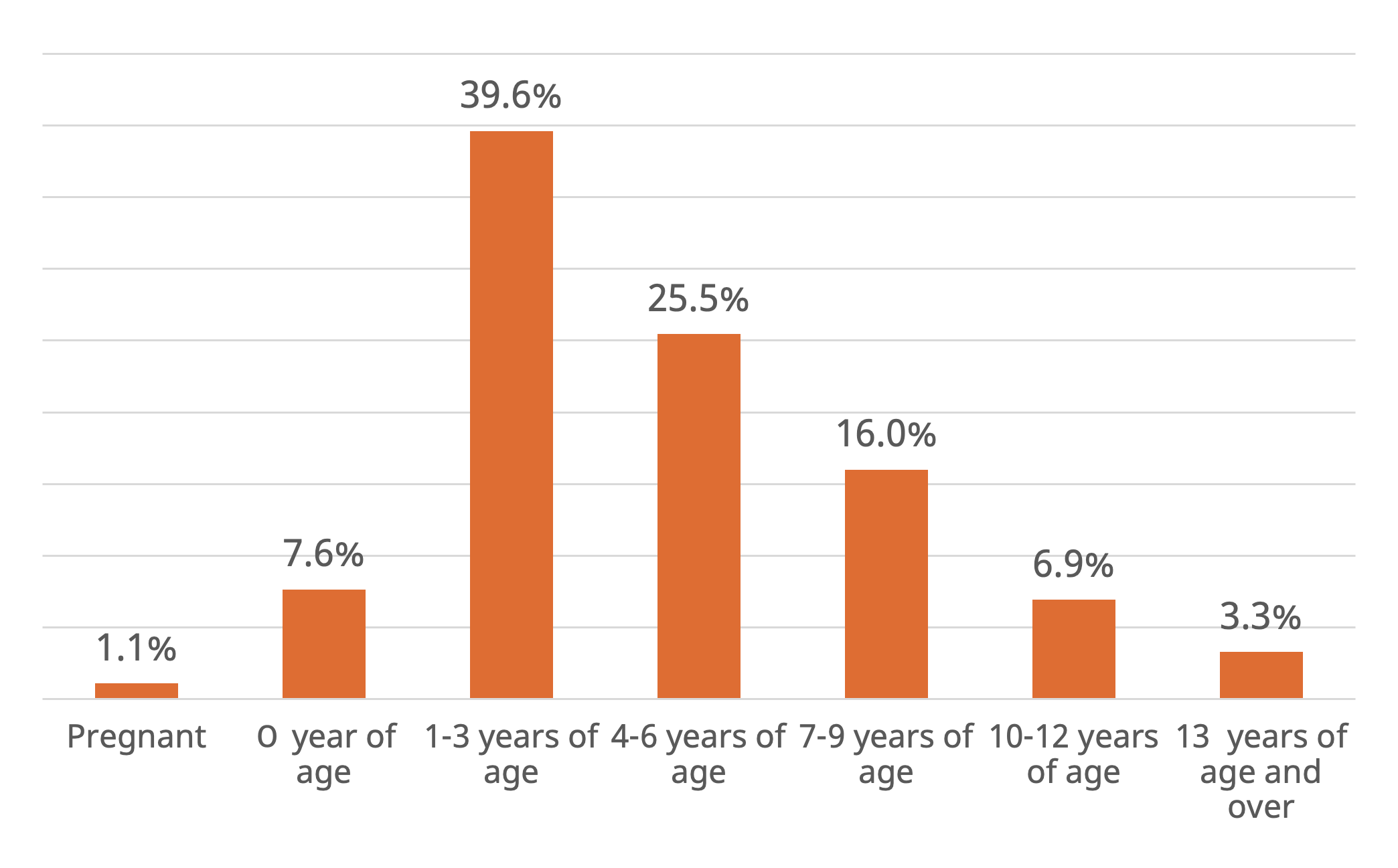

Nearly half of the mothers making inquiries were in their thirties (48.6%), with 30% in their twenties, and 20% in their forties. Regarding their marital status, the highest percentage (37.8%) were separated, 9.2% were married, and 47.0% of the inquiries were pre-single mothers who were not yet divorced, which amounts to almost half (Fig. 10.3). The most common employment status provided was informal employment (35.4%), followed by unemployed (34%) (Fig. 10.4). With regard to the number of accompanying children, those with one child were the most common at over 70% (Fig. 10.5). In addition, the range of children’s ages included 109 children aged 1–3 (39.6%) and 70 aged 4–6 (25.5%), with children below school age, including pregnancies, totaling 73.8% of the total (Fig. 10.6).

By gender, excluding 31 unclear items, girls comprised 51.3% of the total (140) and boys 48.7% (133). A rundown of the trends suggests that SMSH clients tend to be just or not yet divorced, unstably employed, and to have one child below school age. The number, age, and gender of the children involved is extremely important information for the operators. Each household is given one room, but households with multiple children may be permitted to live together depending on the children’s ages.

Some operators also decide whether to admit mothers with older boys based on the opinions of the other residents. Therefore, this kind of advance information is also effective in facilitating rapid matching.

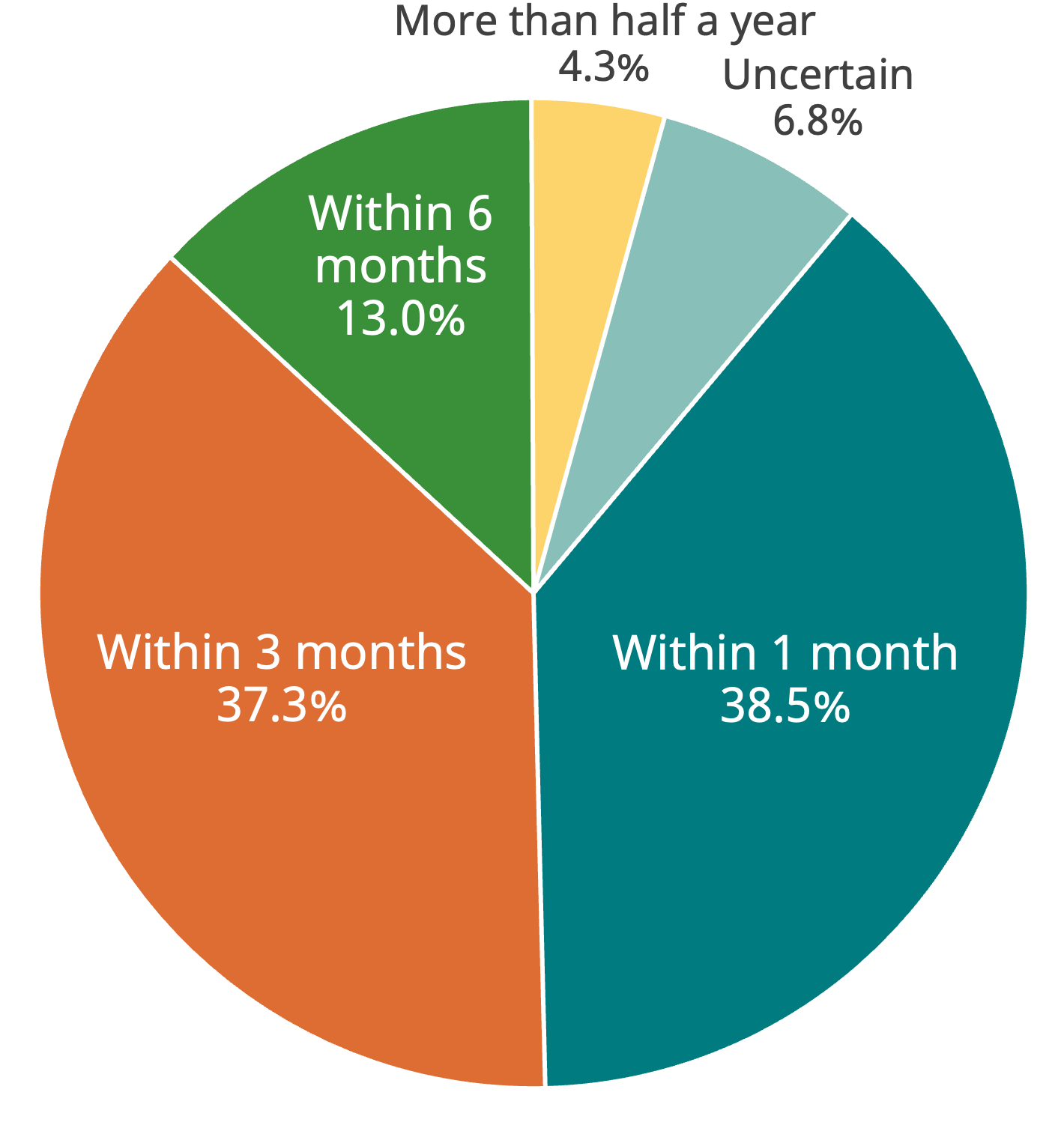

Further, when asked how soon help was needed, 38.5% of those surveyed responded “within one month,” and 37.3% responded “within three months,” indicating that almost 80% were urgently in need of housing. Interviews with operators reveal that there are several cases where divorce and moving are planned to coincide with a child’s entrance into school or where plans for divorce hinge on the promise of housing (). This likely accounts for answers such as “six months or more” or “undecided.”

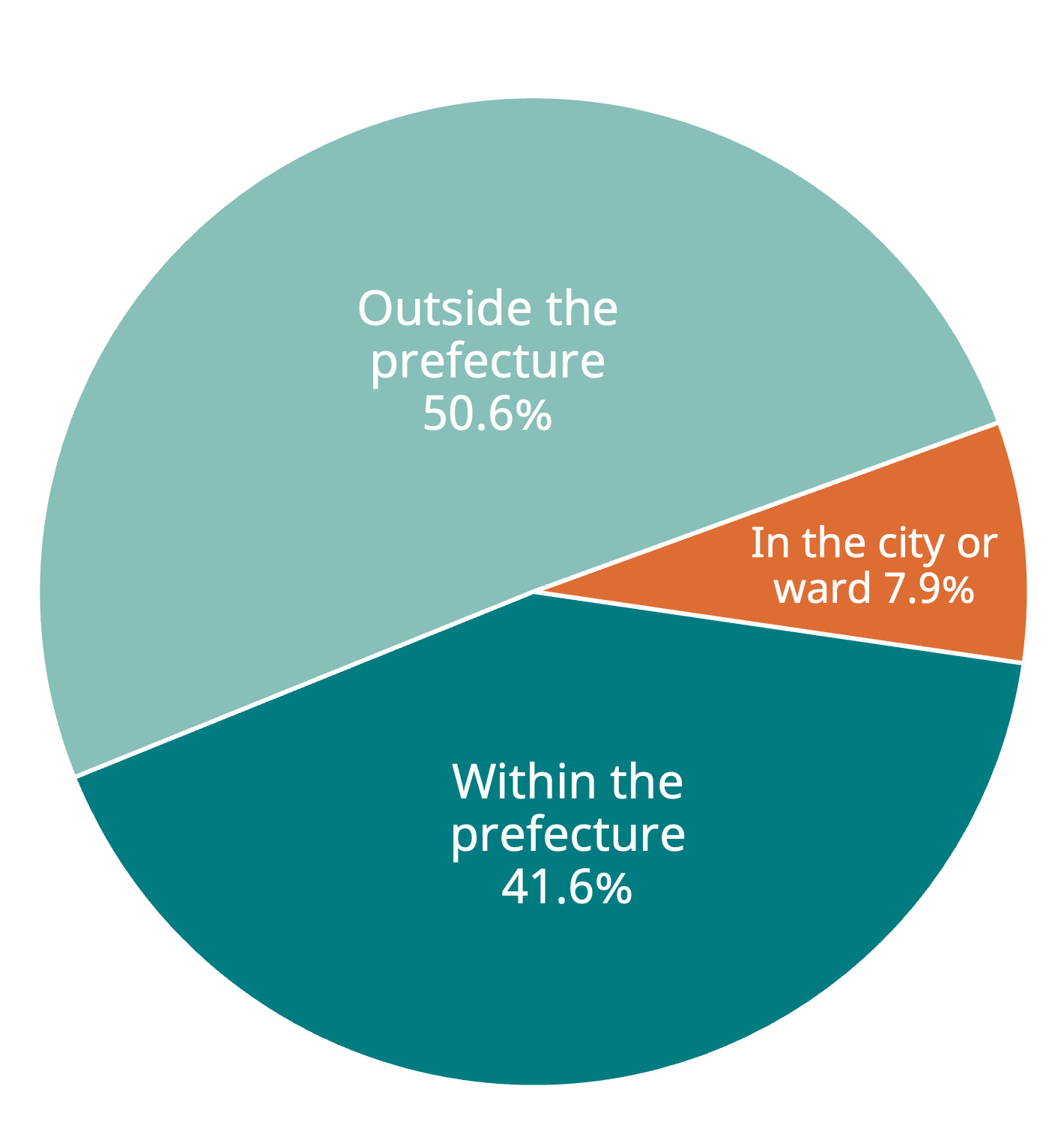

Finally, we researched how women selected locations. According to Kuzunishi (), single when mothers select residential locations outside of the prefecture, they tend to rely on parents or other close relatives, hoping for child-raising support; when moving within cities or similar short distances, they tend to prioritize children’s school districts.

Research on location selection with regard to SMSH includes Kuzunishi and Okazaki (), who analyzed the results of interviews with 15 would-be residents of a house in Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo. Of the interview targets—who were mainly pre-single mothers with small children—only a very few could depend on support from relatives. Many of them had come to Tokyo for college, found employment, married, and continued to live in the capital area. Reasons for not returning to their parents' homes included “worse employment conditions in the provinces” and the desire to avoid “lower educational levels” in relation to factors such as supplementary tutoring or “cram” schools and extracurricular activities. Reasons given by women in the provinces included “looking for good employment conditions” in addition to “wanting a shared house with furniture, etc., where a down payment is not contracted, so moving isn’t too difficult.”

As for the results of the present survey, Fig. 10.8 shows that half the respondents hoped to move out of the prefecture. Of the 135 people hoping to leave the prefecture, 54 (40%) wanted to move to a neighboring prefecture. Out of all respondents, 40% hoped to remain in the same prefecture, and 7.9% in the same city or ward as their current residence.

While over half the respondents selected houses outside their prefectures, 40% of those selected the neighboring prefecture, suggesting an overall trend of wanting to move within as close a range as possible to their current residence.

Community-Created Shared Housing

SMSH is operated by for-profit companies and is heavily biased toward filling vacant units because management success relies on high occupancy rates. Therefore, the conditions for entry are not stringent and mainly depend on the capacity to pay the rent, which is the central point that such companies focus on. Naturally, the rules for occupancy and so on are explained upon entry, but there may not be enough of a common ground between residents and operators, which can lead to problems thereafter.

Currently, SMSH tends to attract two often opposing groups: those needing communal living (oriented toward living with someone) and those needing a guaranteed place to live (nowhere else to go). Therefore, residents frequently clash over lifestyles and mutual assistance. Is it possible, then, to share living principles and satisfy the various desires of the residents as well as the operators? For example, ideau (a single-mother shared house in Osaka made from a remodeled nagaya tenement) has successfully created a housing community by preemptively cultivating a specific SMSH community via social media. It took two years for ideau to open: during that period, they enhanced members' mutual understanding through events and workshops before providing the actual housing after deciding on the occupants at the final stage.

Given the normal practice of using vacant houses and opening them based on practical aspects (securing the housing, deciding on the occupants, and creating a community), ideau’s reversed order of operations is highly interesting. The benefits of this method are that, with occupants selected in advance, vacancies are no longer a point of concern and management goals are easy to meet. Furthermore, because rules and communal living principles shared in advance, post-entry problems are less likely to arise. Meanwhile, disadvantages include the time required to launch the operation as well as the minimal profits; however, this is likely to be a very effective method for NPOs starting up an operation based on welfare or community-building principles.

| Location | 12 minutes on foot from Osaka Metro Kire-Uriwari Station |

|---|---|

| Units | five households (pets accepted) |

| Rent | 70,000 yen (including internet and water) |

| Other | If unemployed upon entry, rent is reduced to 40,000 yen for up to two months until employment is secured |

Table 10.1: Overview of ideau

Multigenerational Housing Beyond the Concept of One Family per House

Kuzunishi () conducted a survey on the actual situation of multi-family shared houses. Glendale Jiyugaoka, located in Tokyo’s Jiyugaoka district, is a multigenerational shared house which opened in 2019. As of April 2021, its residents included two single-mother households, one single woman, one international student, and four older people (aged 95, 94, 93, and 71).

Ito Keiko, CEO of the managing company, Happiness Lands Inc., created this house using existing stock: “we need an environment where older people can live in their own way, in a context as close to their own home as possible” ().

There are also group homes specifically meant for older people in Japan, but as the residents age over time, it becomes difficult for them to support one another. The company examined the potential benefits of establishing diverse households that include but are not limited to older people. Opinions from older people on the concept of multigenerational housing are best exemplified by that of one respondent who said that “young people nearby bring energy, but it would burden them to have them taking care of us all the time” (). By developing policy based on interviews of this kind, they arrived at a framework in which the older people cover costs while the young people are as involved as possible in house management in exchange for low rents. Finally, they took two adjoining houses and made one into a residential home for older people and the other into a shared house for younger people. Costs for the older people include entrance fees ranging from zero to three million yen (repaid over five years) and monthly rents in three possible plans determined by the entrance fee amount (218,000 yen, 278,000 yen, or 360,000 yen). Shared house rents vary according to room size from 50,000 to 109,000 yen, which is considered very reasonable given that its location is only 12 minutes from Jiyugaoka on foot.

International students are able to live rent-free in return for doing part-time work cleaning and preparing meals. Shared house residents can be entitled to dinner on weeknights for an additional 26,000 yen. Before the coronavirus pandemic, residents would gather in the dining room to eat together. Residents would also hold birthday parties, as well as other events such as Christmas and New Year’s. Unfortunately, the coronavirus caused active interaction to be minimized; even so, many residents seem to find it helpful to have others nearby.

For instance, one resident had started working from home due to workplace policy but found it difficult to make progress when their small child was making noise. Another resident noticed the issue and offered to look after the child, allowing for the worst difficulties to be overcome. A different resident lived in the shared house and performed house work services, using the extra time to study for promotion exam and achieve financial independence.

In a little less than two years since Glendale’s opening, one of the older residents has already passed away; he was able to enjoy a full life within the house until the end. Ito, the CEO, received heartfelt thanks from the deceased resident’s family and said that she felt convinced that “we can make more out of the potential for living with someone, not with family, yet not alone” ().

Table 10.2: Overview of Glendale Jiyugaoka

| Location | 12 minutes on foot from Toyoko Line Jiyugaoka Station |

|---|---|

| Units | five households (pets accepted) |

| Rent | 50,000 to 109,000 yen (including Internet and water) |

| Other | Weeknight dinner service available for 26,000 yen. |

Single-Mother Shared Housing as a Space for Inclusion

According to NPO members, consultations with single mothers involve serious matters such as “I have nowhere to go if I leave,” “I’m staying temporarily in a hotel/with friends,” “I need to get away from my violent husband right now,” “my child is disabled, can we still move in?,” “can I still move in if I’m on welfare?,” “can I still move in if my child is in high school or older?,” and so on (). Further, various issues after entry have arisen, including mothers with mental illness, which can cause difficulties with cohabitation. If measures are taken too late and the problems worsen, the operators face further issues and profitability falls.

Since 2019, the NPO National Single Parent Residential Support Cooperative has comprehensively increased its operator information network. Common issues have also become clear on a chronological axis, from establishment through entrance support and during residence. Interaction among operators and accumulated case studies are provided as feedback for operators and made use of in operations.

In the last few years, some operators have collaborated with local companies and raised funds via donations to provide free meals and shelter or to create food banks. In addition, free cram schools have been established in some cases to ensure that children have a place to be. These initiatives are innovative in their focus on supporting not only residents but also local households with children and older people.

As seen above, the role of SMSH is not only to provide shelter simply as a physical residence space but also to create knowledge and know-how on working within the gaps in the system, eventually confronting issues faced by residents at the level of residential and regional welfare by establishing a network that opens up housing to communities within the framework of the commons.

SMSH doesn’t have a massive housing demand and is regarded as a minor factor in the local housing market. However, it is an urban space for inclusion that can accept various social classes such as ethnic minorities, sexual minorities, single mothers, and members of low-income groups. Such a space enhances the markets' resilience and improves the vitality of the urban economy. This is to say that, while the market for these spaces is small, their impact on society is enormous. In this context, SMSH is an indispensable player in the housing market with a significant public value in urban spaces.

Bibliography

- MHLW, 2017

- Family Welfare Division, Child and Family Policy Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW). (2017). Nationwide Survey on Single Parent Households 2016. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000188147.html

- Kuzunishi, 2017

- Kuzunishi, L. (2017). Living in Poverty of Single-mother Households. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyouronsha. (In Japanese).

- Kuzunishi, 2018a

- Kuzunishi, L. (2018a). Considering Housing with Cares, Diversity of Shared Houses for Single-mothers. Uzo Nishiyama Memorial Library. (In Japanese).

- Kuzunishi, 2021

- Kuzunishi, L. (2021). The Situation of Housing poor that obstructing from Children's Growth and Health: From the Case Study of Single Parents. Journal of the Japan Society of Home Economics Family Relation, 40, 73–80.

- Kuzunishi et al. 2006

- Kuzunishi, L. and Onishi, E. (2006). A Study on Housing Situation of Single Mother Households and its Regional Gap. Journal of the Housing Research Foundation, 32, 261–271.

- Kuzunishi, 2018b

- Kuzunishi, L., Murosaki, C., & Okazaki, A. (2018b). The Nationwide Trend of Shared Housing for Single Mother Households—The Situations of Management, Type of Building, Rent Amount, and Care Services. Urban Housing Sciences, 103, 177–186.

- MLIT, 2019

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MLIT). (2019). Housing and Land Survey 2018. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jyutaku/2018/tyousake.html

- MHLW, 2020

- Vital Health and Social Statistics, Director-General for Statistics and Information Policy, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2020). Overview of Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions 2019. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa19/dl/14.pdf

- Yoshitake, 2019

- Yoshitake, R. (2019). Determinants of Recipients of Public Assistance Among Single-Mother Households Living in Poverty: Factors Determining Why Public Assistance is not Received. Journal of Welfare Sociology, 16, 157–178. (In Japanese).