11. Digital Transformations in Planning: An Australian Context

- Matthew Kok Ming Ng, Research Fellow, City Futures Research Centre, The University of New South Wales (Australia)

- Balamurugan Soundararaj, Research Associate, City Futures Research Centre, The University of New South Wales (Australia)

- Christopher Pettit, Professor, City Futures Research Centre, The University of New South Wales (Australia)

Introduction

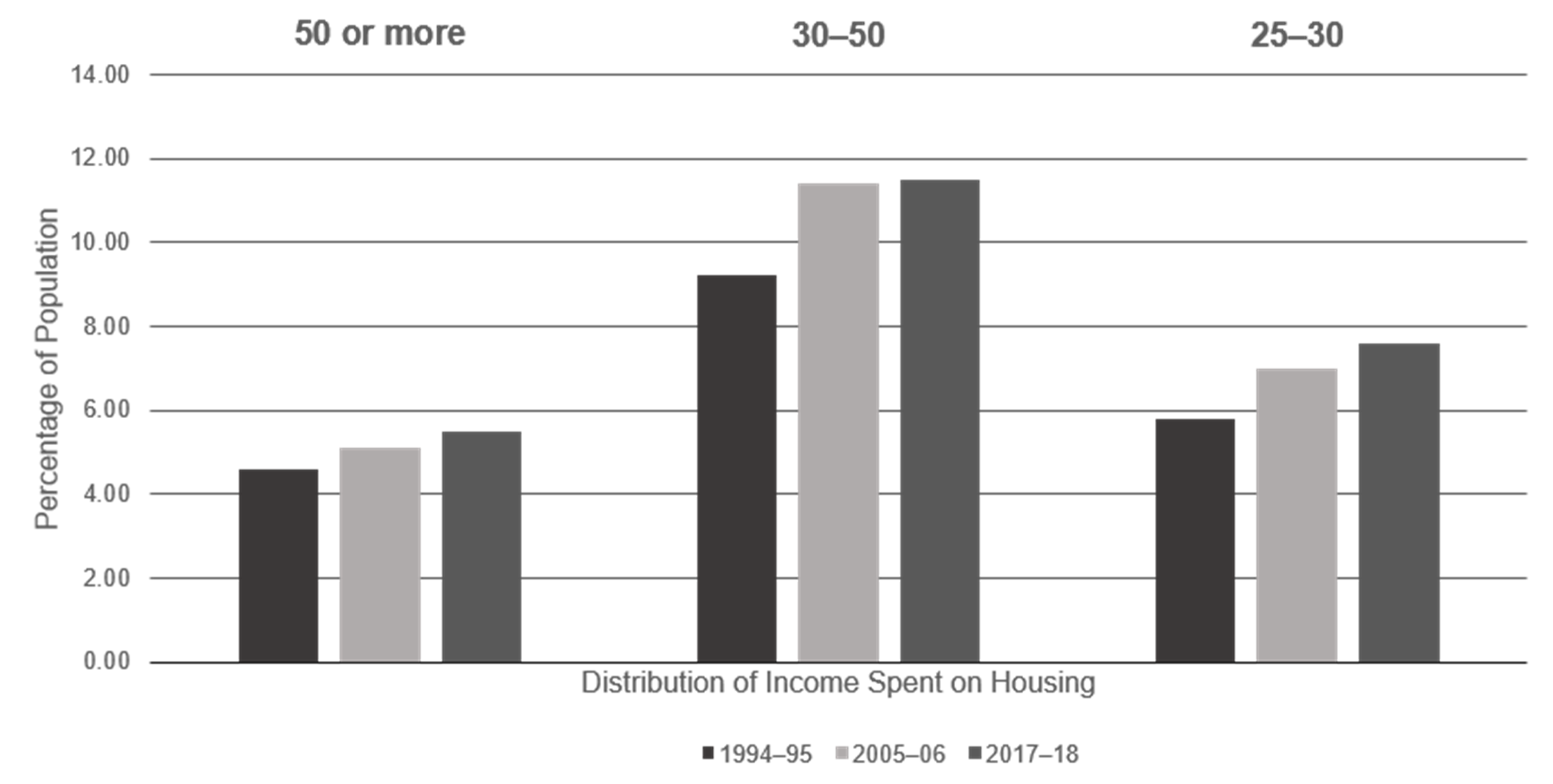

Australian cities face numerous housing challenges, the most prominent of which is the housing shortage faced by the country over the past three decades (). Indeed, up to 2009, it was estimated that approximately 180,000 additional dwellings were needed to meet housing demand (NHSC, 2010). However, to date, this gap has since continued to widen (; ). Today, the disparity between housing supply and demand has become a highly topical subject. It has been credited as the root cause of the housing stress1 experienced by many Australians (). Most recently, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021) estimated that, in 2018, approximately 17% of Australians spent over 30% of their gross annual incomes on housing costs, with a more concerning 5.5% of the population spending more than half of their incomes on housing. This figure had risen year-on-year since 1994, when 13.8% of Australians were considered to be under housing stress (see Fig. 11.1; ).

This is an issue that has become particularly pressing when considered in terms of demographic characteristics and geography. Not surprisingly, it was noted that lower-income households disproportionately feel housing stress; in more urban regions, close to 48% of low-income households were considered to be under some financial stress concerning housing costs ; ). Having been poorly addressed, these issues have continued to contribute to numerous urban challenges. In many Australian cities today, issues such as homelessness, housing affordability, and increasingly disparate intergenerational home-ownership rates have become the most tangible symptoms of the housing crisis (; ; ; ). Moreover, coupled with their persistence over time, these issues have made achieving urban equity amongst the country's most vulnerable demographic groups all the more difficult.

However, despite these longstanding consequences, housing delivery in Australia remains hindered by a multiplicity of unresolved factors. These include land supply issues, zoning and development restrictions, lengthy planning processes, and a lack of coordination between the development bodies overseeing infrastructure and housing delivery (; ; ). add that, whilst increasing capacity for home building is undoubtedly crucial, housing policies addressing it need to be more carefully considered to ensure the consistency of housing delivery and its accessibility across all demographic groups both financially and geographically.

If we consider these issues more tangentially, it can be argued that the facilitation of better housing delivery is crucially lacking in the critical exchange of data and information surrounding the housing stock at present. Indeed, for housing development processes in Australia to be more efficient and transparent, critical pathways to improved data management, visualization, and analysis of housing stock need to be considered (). This is a gap that has not been fully addressed yet and which has contributed detrimentally to housing delivery in the country. In fact, up to more recent years, aspects of data management and analytical communication had been relatively overlooked. This has since changed, with an increase in the digitization of planning data and the proliferation of analytical tools that seek to create more data-driven and responsive urban services ().

These linkages between digitization and housing are explored more deeply in this chapter with respect to housing data as a critical resource in the digital transformation of planning in Australia. Opportunities that accompany this shifting paradigm are discussed with a view toward potentially shifting planning practice through the introduction of a singular housing database for Australia. In this context, we detail how citizen-centered approaches in this ongoing transformation may facilitate more granular communication around current housing development conditions, greater community engagement and ownership, and the democratization of planning technology and data that enable greater community participation. Furthermore, it we show how such a platform may facilitate the essential exchange of knowledge that precedes development and delivery.

Background

In 2020, the Planning Institute of Australia released a statement on the guiding principles for the future of digital planning systems. It was noted in the report that, whilst there had been a marked proliferation of tech- and data-driven planning assistance tools, there were reformations of Australia’s underlying digital data infrastructure that also needed to be considered (). Indeed, it has since become clear that, given the increasing digitization across all domains of planning and development, strategic decisions need to be made in both data administration and operationalization. These are pressing requirements that shed light on the central role that national governments must play in this ongoing transformation () which, ultimately, will shape the future models of Australia’s data governance. Considering this, posited that approaches to the development of data management systems and downstream analytical tools needs to be more collaborative. They put forward the notion that government agencies (as data providers) and external agents (as the developers of these necessary toolkits) both require mutual support in identifying and addressing a city’s national development priorities.

This integral step was also noted by , who suggests that, whilst a more cooperative dynamic was essential, national government also needed more tactical direction in their “curation and management of data assets to support strategic [planning] priorities.” In this vein, there is a growing call for the government to foster a more enabling environment in the co-design and co-development of digital platforms in Australia. As such, policies that underpin this movement need to be aligned across all sectors (). In this process, there may be more opportunities for individuals, institutions, and commercial entities to aid with and co-create data-driven approaches and formulate solutions that can meet the remit of future development planning goals. and maintain that this will require current data custodians to recognize the value of open public data, prioritize their access, and work towards their standardization; this, in turn, may dramatically boost innovation in a way that has not yet been realized in Australia.

Globally, the digital transformation of planning and city data has in fact now become almost commonplace. In cities around the world, access to key information on the city has burgeoned in the form of city dashboards. For example, in the United Kingdom’s London CityDashboard, climate sensors and real-time public transport and traffic data are integrated into a single interface (; ; ). Additionally, in San Diego, the PerformSD dashboard summarizes key metrics on public service performance, crime, transportation, and other important socioeconomic data obtained from numerous public service departments that pertains to the progress and improvements of numerous policy indicators (). In Australia, similar work on city dashboards has also been undertaken (e.g., the Sydney City Dashboard by the University of New South Wales) to offer citizens a single point of access to similar data (). These examples provide their citizens ready visualizations of key city information; this provision allows citizens to make informed decisions about engaging with their environment, and these choices can ultimately be quantified in their feedback ().

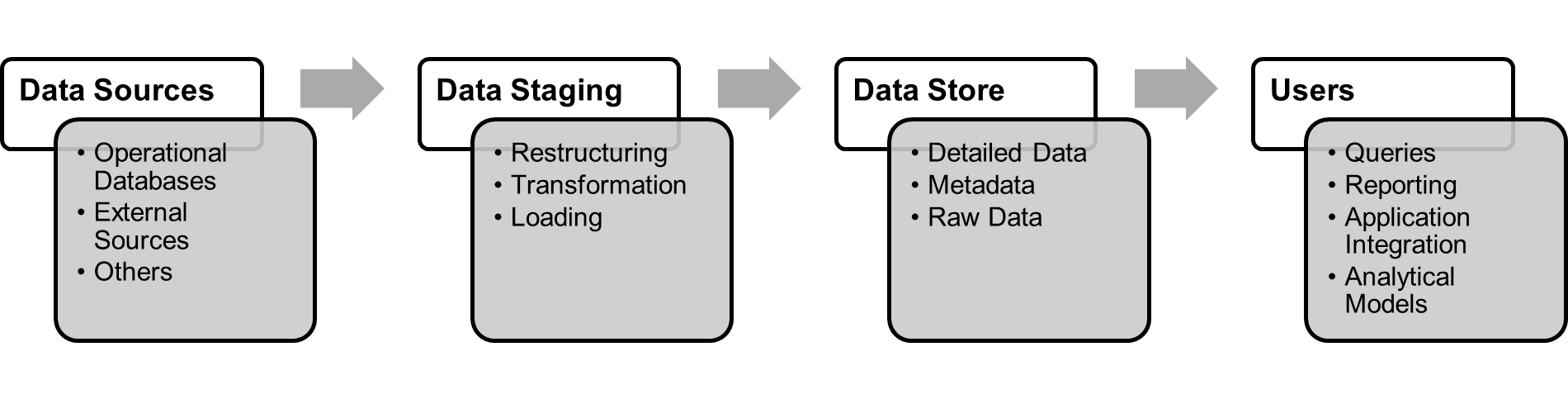

However, as pointed out by , caution should be observed given the level of abstraction that accompanies the representation of city data and given the choice of what data is presented. Further, it has also been suggested by Mattern (2013) and Barns (2018) that these initiatives provide citizens only superficial access to data. Instead, separately, they suggested that more value could perhaps be gained should citizens or other development agents be allowed access to government data, in addition to being given choices about its utilization (). Platforms that offer these services, colloquially named data stores, place less emphasis on the moderation and selective communication of data, leaning instead towards open or paid access to a larger gamut of data formats to all user types (). These platforms are aligned with the “Government as a Platform” digital strategy, where the delivery of data is completed through shared registers and APIs. Yet at the same time, their downstream use remains undetermined (ref. Fig. 11.2; ; ). The objective here can be loosely articulated as to make available the widest diversity of data at the largest volume to the highest number of people. This is reflected in their “one-to-many structure”, wherein numerous distinct applications can be derived from the same datasets ().

Considering this, data stores need to be designed around the needs of the user given the far-reaching impacts that alterations or modifications can have on services and the analytical models that depend on it. However, there presently also remain numerous challenges to making data stores operational both in Australia and globally. As indicated by in their development of QuerioCity—an integrated database of city data—critical structural, functional, and semantic considerations must be made to make the integration of existing datasets possible. They stress that urban data is often highly disparate and exists in multiple formats and structures. Consequently, datasets ingested into data stores need to be restructured, linked, and made relational to meet the primary objective of creating a single comprehensive data ecosystem (; ). This includes the creation of a common semantic structure across dataset properties that allows rapid queries to be made by users, instead of a manual “mapping” of attributes within these large datasets ().

Critically, this remains a difficult task as it may be unrealistic at present for many data custodians to adopt a single schema. These challenges appear to be ubiquitous and are also applicable to Australia (; ; ). Here, key city data are also held by a diverse set of custodians in an even more varied range of formats. For example, Geoscape Australia, the national provider of location data, offers numerous data products that include key building attributes (e.g., building footprints, materials, height, area), land parcel data (e.g., land ownership, zoning codes, valuation information), and geocoded address files; however, these exist as separate datasets that need to be queried individually. The resulting datasets include numerous data forms (CSV, GeoJSON, JSON, ESRI shapefiles, etc.) that will also need to be made relational. Utilizing these datasets and ensuring their interoperability requires significant time costs for processing and restructuring.

Specific housing datasets in Australia are also highly disparate and disjointed. There is often little information on the housing stock available to the general public; and, where data is available, they are fragmented or available only on an aggregated scale. Furthermore, these datasets are only made fully available through a paid subscription, which adds an additional barrier to both research and the development of downstream tools. Furthermore, should these datasets be utilized in tandem with other relevant datasets from other major providers such as the Australia Bureau of Statistics or the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Group, subsequent analyses may become less granular given the varying levels of data aggregation. As a result, there are numerous bureaucratic and procedural barriers facing researchers and policymakers alike if they desire to implement evidence-based planning and downstream analytical modelling in the country.

An Integrated Australian Housing Data Platform

The challenges mentioned above distill only a minute part of the multidimensional challenges researchers and policymakers face in obtaining and operationalizing available housing data in Australia. These challenges often manifest themselves tangibly in the coordination between developmental and institutional agents, which invariably leads to disruption and delay in activities related to housing delivery. Further, given the current pace of growth and urbanization in the country, there is mounting pressure on resource allocation and planning capacities for much-needed housing delivery. These are issues that the national government has recognized, and with smart infrastructure and planning policies now introduced (e.g., New South Wales [NSW] Smart Infrastructure Policy and Smart Places Strategy), active calls for technology-focused, citizen-centered approaches are now being made (; Pettit et al., 2017). Moreover, since its introduction, the NSW Government’s smart city development policies have stimulated many discussions on rethinking how the country's planning and development systems and processes can be enhanced (; ). Despite this, however, a more systematic and coordinated means to facilitate these vital exchanges has yet to be developed or adopted.

Nevertheless, opportunities to address these issues do exist with particular respect to the nation's ongoing pursuit of the digital transformation of its planning system. Here, there is potential not only to remedy Australia's need for a coordinated system of data management and exchange, but there are also actionable avenues to create more efficient, transparent, and responsive systems than those that already exist today. In particular, it is believed that tangible change can be affected by the consolidation of the diverse existing housing datasets, the maintenance of their relevance and validity, and the prioritization of data accessibility for all stakeholders, including the general public. These activities are integral in promoting several required downstream activities concerning Australia's housing data: first, they facilitate the standardization of common built-environment data, sources, and processes to allow data integration and interoperability between multiple platforms and applications; second, they allow for more rapid large-scale data exchanges to be made from a single platform without the need for lengthy pre-processing steps. By reducing the impact of these initial impediments, the development of such a data governance system would inevitably be valuable in promoting and expediting innovation and development in terms of policymaking and other high-value technological advancements.

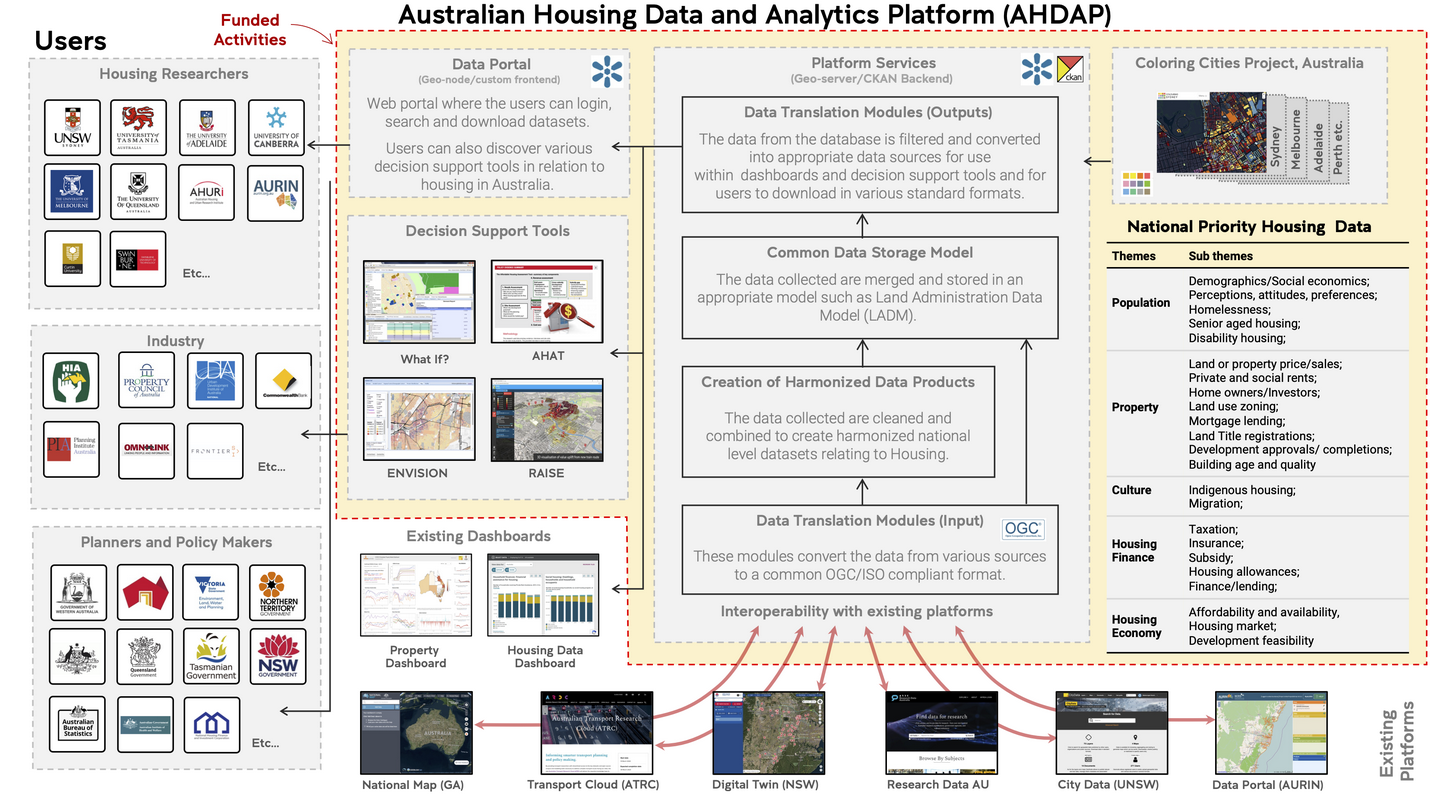

These are the opportunities and challenges recognized by the University of New South Wales City Futures Research Centre in their ongoing development of a novel Australian Housing Data Analytics Platform (AHDAP). AHDAP seeks to address Australia's housing data disparity by creating a consolidated and harmonized housing data governance model. In its current stage of development, AHDAP is a federated data platform capable of large-scale ingestion, standardization, and management of all digital data on housing and the built environment in the country. This includes the integration of the many existing and varied datasets held by individual custodians across the nation. For the first time in Australia, the platform connects numerous critical private and public institutions in academia, industry, and government who also recognize the concerted effort required to deliver and implement such a novel data governance model in the country.

AHDAP is able to overcome the current shortfalls of data management in Australia through several essential tracks. First, by harmonizing the large mass of housing data in accordance with global management standards (), rapid, multiscale, and multidimensional analysis and simulations can be implemented using previously disjointed datasets to evaluate and substantiate future development scenarios more holistically. Moreover, this addresses present redundancies for policymakers and researchers by commissioning surveys to repeatedly collect the same data used downstream. As a result, significant time and opportunity costs associated with such activities are effectively minimized with a single trusted repository. The breadth of data and the ease with which it can be rapidly obtained and analyzed using AHDAP are central to accelerating policy evaluation and development delivery; however, more importantly, they are crucial to better understanding the linkages between housing, communities, and underlying land use dynamics. Indeed, for policy and research in Australia to be relevant, they must be supported by data that allows for timely and dynamic interventions at the correct locations and spatial scales.

Second, with its planned suite of analytical and decision support toolkits, the development of AHDAP holds significant potential for improving the interrogation of current and future housing development scenarios. In particular, the integration of the proven and validated RAISE and WhatIf? toolkits that preceded AHDAP creates an extensive capacity to hypothesize and simulate possible development futures with regard to land and property value changes, infrastructure allocation, and real-time development decision support (, ). These are critical insights that are often inadequately addressed in reviews of the complex land supply, demand, and allocation issues that have contributed to the country's current housing delivery situation. The advancement of these indispensable tools creates opportunities to develop and elevate current metrics to account for these issues, and to communicate and visualize more effectively the impact of planning and development choices with respect to aspects such as mobility, accessibility, well-being, and diversity, which are fundamental dimensions of the lived experience of Australians. These outputs are made accessible by AHDAP to essential development stakeholders and agents, as well as to the general public, where such data can inform and empower citizens through the insights gained from such spatial intelligence.

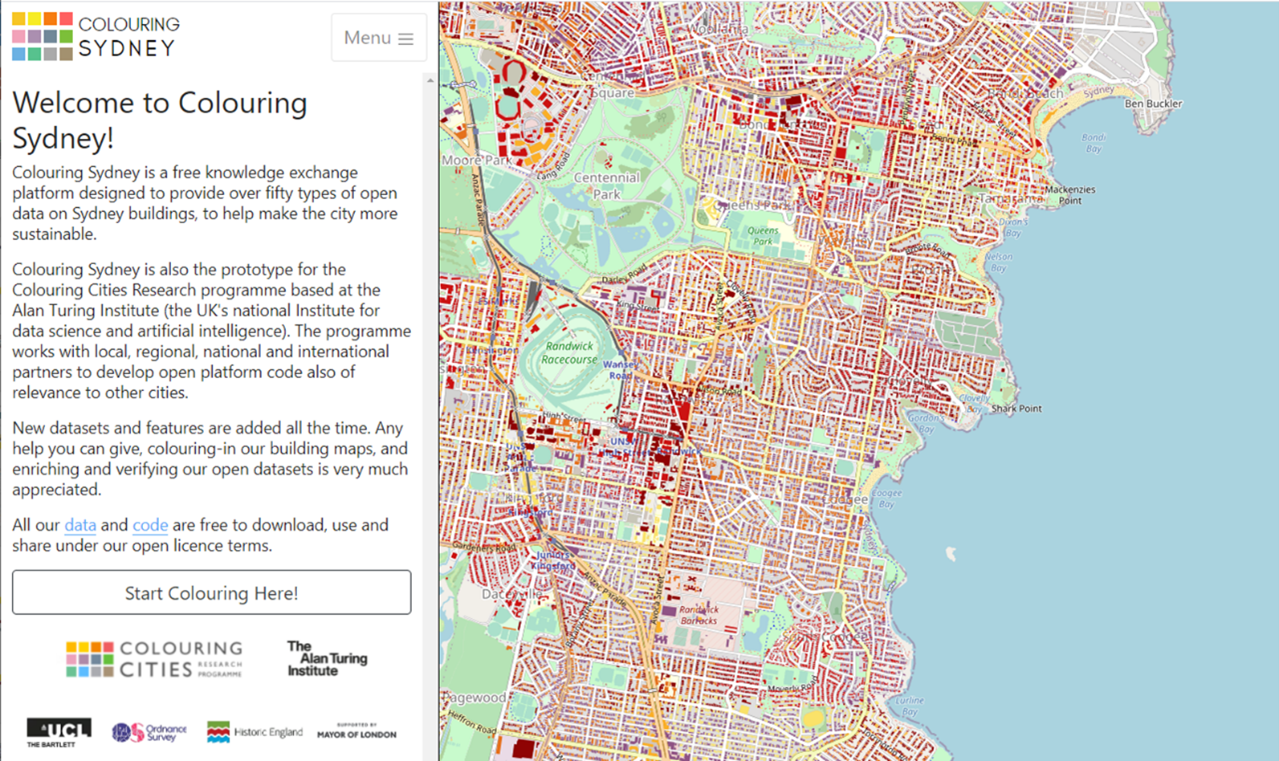

Finally, with the integration of Colouring Australia—a collaboration with the Alan Turing Institute’s Colouring Cities Research Programme—AHDAP can leverage new public engagement methodologies and data collection approaches. The Colouring Australia tool was born from the acknowledgement that obtaining accurate and granular building-level attributes is not typically feasible given that it is an onerous exercise. As such, Colouring Australia is positioned as a novel citizen science platform that is able to rapidly collect and disseminate voluntarily provided geographical information on Australia’s building stock. Indeed, amidst the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, digital engagement has become further legitimized and its role in enabling better outreach to more traditionally excluded audiences has been proven. Diversity and inclusion are central themes in its design and development; this can be seen in its focus on the “local” with data collection and inputs open to almost all demographic groups. As such, it allows local communities to both contribute voluntary geographical information and validate data within their local environment in a way that does not require extensive digital training.

These benefits of this are multifold; primarily, in light of aspirations to encourage participatory policy and solution formulation for local urban challenges, the empowerment and data ownership gained from this engagement are important to increasing support for and trust in Australia's planning processes. In a similar vein, community engagement and data collection through this citizen science space offer a more novel approach to enhancing data granularity and accuracy, which will ultimately be used to improve the current data offering in AHDAP and elevate the accuracy of its corresponding toolkits. Further, as part of the Colouring Cities Research Programme,2 the platform is approached in highly collaborative ways with both global and local research institutions, which allows for significant knowledge exchange in terms of both policy and operationalization. This also includes peer-reviewed work on data analytics and machine learning models to ensure the development and deployment of rigorous toolkits for all cities. Ultimately, there is vast potential for a singular housing data platform such as AHDAP to herald a new shift in the way communities, public stakeholders, and development agents in Australia engage with technology and data throughout the entire planning and development process.

Conclusions

In this chapter, we have discussed the changing landscape of planning and development in Australia. First, we have indicated how critical data is as a commodity for policy makers and other development agents when it comes to creating more value and driving innovation in tech- and data-driven services and applications. In this respect, we have highlighted how widening access to data for these key user groups may aid in identifying key areas of improvements and development, particularly in the realm of Australia’s housing delivery. With this in mind, we have introduced the Australian Housing Data Analytics Platform, which is a digital platform in its infancy. The platform is able to support urban researchers, policy makers, and industry by providing access to a comprehensive array of data and decision-support tools that assist in addressing the challenges facing the Australian housing market, including housing supply, affordability, and stress. The platform endeavors to follow the PlanTech principles developed by the Australian Planning Institute, including the directive that digital planning infrastructure should be public infrastructure built with open technology. In this chapter, we have also outlined one of the key digital components comprising AHDAP, Colouring Australia. This open-source digital platform provides a means for democratizing access and contributions to knowledge of the city through a crowdsourcing approach. This platform conceives of data as a public good and enables citizens to access information and analytics in a way that is not currently possible in the country. The next steps in the development of AHDAP are to improve the accessibility of a wider range of digital housing assets across Australia which in themselves provide public value by supporting evidenced-based decision making and improved planning of our cities.

-

Housing stress is identified in households that spend over 30% of gross income on housing costs (). ↩︎

-

Current (2021) partners include The American University of Beirut (Lebanon), The University of Bahrain and Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities (Bahrain), The University of New South Wales (Australia), University College London and the Alan Turing Institute (London), The National Technical University of Athens (Greece), and The Leibniz Institute for Ecological Urban and Regional Development (Germany). ↩︎

Bibliography

- ABS, 2019

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). (2019). Housing occupancy and costs, 2017–18.

- AIHW, 2021

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). (2021). Housing assistance in Australia. Cat. no. HOU 325.

- Al-Ani, 2017

- Al-Ani, A. (2017). Government as a platform: services, participation and policies. In M. Friedrichsen & Y. Kamalipour (Eds.), Digital Transformation in Journalism and News Media (pp. 179-196). Springer.

- Barns, 2018

- Barns, S. (2018). Smart cities and urban data platforms: Designing interfaces for smart governance. City, Culture and Society, 12, 5-12.

- Barns et al., 2017

- Barns, S., Cosgrave, E., Acuto, M., & Mcneill, D. (2017). Digital infrastructures and urban governance. Urban Policy and Research, 35(1), 20–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2016.1235032.

- Brown, 2012

- Brown, G. (2012). Public participation GIS (PPGIS) for regional and environmental planning: Reflections on a decade of empirical research. Journal Of The Urban & Regional Information Systems Association, 24(2), 7-18.

- City of San Diego, 2021

- City of San Diego, (2021), City of San Diego Performance Dashboard. http://performance.sandiego.gov.

- De Lange, 2018

- De Lange, M. (2018). From real-time city to asynchronicity: exploring the real-time smart city dashboard. In Sybille Lammes, et al (Eds.), Time for Mapping: Cartographic Temporalities (pp. 238-255). Manchester University Press.

- Dunleavy & Margetts, 2015

- Dunleavy, P., & Margetts, H. (2015). Design principles for essentially digital governance. Paper to the 111th annual meeting of the American political science association. American Political Science Association, 1-31.

- Gil-Garcia & Henman, 2019

- Gil-Garcia, J. R., Henman, P. & Maravilla, M. A. A., (2019). Towards “Government as a Platform”? Preliminary Lessons from Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Proceedings of Ongoing Research, Practitioners, Posters, Workshops, and Projects of the International Conference EGOV-CeDEM-ePart 2019, 173-184.

- Goldsmith and Crawford (2014)

- Goldsmith, S. & Crawford, S. (2014). The responsive city: Engaging communities through data-smart governance. John Wiley & Sons.

- Gurran & Bramley, 2017

- Gurran, N. & Bramley, G., (2017). Housing, Property Politics and Planning in Australia. In N. Gurran & G. Bramley (Eds.), Urban Planning and the Housing Market: International Perspectives for Policy and Practice (pp. 259-290). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kitchin and McArdle, 2016

- Kitchin, R. & McArdle, G., (2016). Urban data and city dashboards: Six key issues. Programmable City Working Paper, 21, 1-21.

- Kitchin et al. (2016)

- Kitchin, R., Lauriault, T. P., & McArdle, G. (2015). Urban indicators and dashboards: epistemology, contradictions and power/knowledge. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 43–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2014.991485.

- Kresse & Fadaie, 2013

- Kresse, W. & Fadaie, K., 2013. ISO standards for geographic information. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Li et al., 2020

- Li, W., Batty, M. & Goodchild, M.F., (2020). Real-time GIS for smart cities. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 34(2), 311-324.

- Lopez et al. (2012)

- Lopez, V., Kotoulas, S., Sbodio, M. L., Stephenson, M., Gkoulalas-Divanis, A. & Mac Aonghusa, P., (2012). Queriocity: A linked data platform for urban information management. The Semantic Web – ISWC 2012. Springer, 148-163.

- Murray, 2020

- Murray, C.K., (2020). Time is money: How landbanking constrains housing supply. Journal of Housing Economics, 49(101708), 1-10.

- O’Reilly, 2011

- O'Reilly, T., (2011). Government as a Platform. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 6(1), 13-40.

- Pan et al., 2016

- Pan, Y., Tian, Y., Liu, X., Gu, D., & Hua, G. (2016). Urban big data and the development of city intelligence. Engineering, 2(2), 171-178.

- Parsell & Marston, 2012

- Parsell, C. & Marston, G. (2012). Beyond the “At Risk” Individual: Housing and the Eradication of Poverty to Prevent Homelessness. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 71(1), 33-44.

- Pawson, 2020

- Pawson, H., Milligan, V. & Yates, J. (2020). Housing Policy in Australia: A Reform Agenda. Housing Policy in Australia. Palgrave Macmillan, 339-358.

- Pawson et al. (2021)

- Pawson, H., Randolph, B., Aminpour, F. & Maclennan, D. (2021). Housing and the Economy: Interrogating Australian Experts' Views, UNSW City Futures Research Centre.

- Pettit, Lieske, and Jamal (2017)

- Pettit, C., Lieske, S. N. & Jamal, M. (2017). CityDash: Visualising a changing city using open data. Planning Support Science for Smarter Urban Futures, Springer, 337-353.

- Pettit et. al., 2020

- Pettit, C., Shi, Y., Han, H., Rittenbruch, M., Foth, M., Lieske, S., van den Nouwelant, R., Mitchell, P., Leao, S., Christensen, B. & Jamal, M. (2020). A new toolkit for land value analysis and scenario planning. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 47(8), 1490-1507.

- Pettit et al., 2015

- Pettit, C.J., Klosterman, R. E., Delaney, P., Whitehead, A. L., Kujala, H., Bromage, A. & Nino-Ruiz, M. (2015). The Online What if? Planning Support System: A Land Suitability Application in Western Australia. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 8(2), 93-112.

- Phillips & Joseph, 2017

- Phillips, B. & Joseph, C. (2017). Regional housing supply and demand in Australia. Centre for Social Research & Methods Working Paper (Australian National University), 1/2017, 1-22.

- PIA, 2020

- PIA, Planning Institute of Australia,.(2020). PIA PlanTech Principles. Canberra, Australia.

- Pope, 2019

- Pope, R. (2019), Playbook: Government as a Platform, Ash Centre for Democratic Governance and Innovation (Harvard Kennedy School).

- Rahman & Harding, 2014

- Rahman, A. & Harding, A. (2014). Spatial analysis of housing stress estimation in Australia with statistical validation. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, 20(3), 452-486.

- Reponen, 2017

- Reponen, S. (2017). Government-as-a-platform: enabling participation in a government service innovation ecosystem. Master’s Thesis. Helsinki: School of Business, Aalto University.

- Schieferdecker, 2016

- Schieferdecker, I., Tcholtchev, N. & Lämmel, P., (2016). Urban data platforms: An overview. Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Open Collaboration Companion, 1-4.

- Wilkins & Lass, 2018

- Wilkins, R. K. & Lass, I. (2018). The Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 16: The 13th Annual Statistical Report of the HILDA Survey. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne.

- Wood et al., 2015

- Wood, G., Batterham, D., Cigdem, M. & Mallett, S. (2015). The structural drivers of homelessness in Australia 2001-11. AHURI Final Report, 238, 1-100.

- Yates & Bradburry, 2010

- Yates, J. & Bradbury, B. (2010). Home ownership as a (crumbling) fourth pillar of social insurance in Australia. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(2), 193-211.

- Yates and Wulff, 2005

- Yates, J. & Wulff, M. (2005). Market provision of affordable rental housing: lessons from recent trends in Australia. Urban Policy and Research, 23(1), 5-19.

- Yigitcanlar, 2020

- Yigitcanlar, T., Kankanamge, N., Regona, M., Ruiz Maldonado, A., Rowan, B., Ryu, A., Desouza, K. C., Corchado, J. M., Mehmood, R. & Li, R. Y. M. (2020). Artificial intelligence technologies and related urban planning and development concepts: How are they perceived and utilized in Australia?. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 187, 1-21.

- Young et al., 2021

- Young, G.W., Kitchin, R. & Naji, J. (2021). Building City Dashboards for Different Types of Users. Journal of Urban Technology, 28(1-2), 289-30.