2. Public Value in the Late Modern City

- Hiroyuki Mori, Professor of Economics, Ritsumeikan University (Japan)

- Ari-Veikko Anttiroiko, Adjunct Professor, Tampere University (Finland)

Introduction

Cities are dense urban settlements that serve as the loci of consumption, commerce, power, and security (see ). They are as such more than just a group of people who settle down and interact in a given area. Cities as urban dissipative structures facilitate processes that are both local and relational. This is evident in how wars, economic booms, disruptive innovations, depressions, and the rise and fall of trade routes have shaped cities throughout history. At the highest level of abstraction this implies that each city as an instance of local choice evolves in a dialectic relationship with its societal and ultimately global contexts.

It goes without saying that people living in the same area is a necessary condition for the existence of a city, as is its physical environment. However, the social nature of the city becomes comprehensible only when we identify local instances of collective action, structures of human interaction, and the spatial organization of the local society. Regarding late modern cities in the developed world and their evolution both from industrial to postindustrial conditions and from local orientations to global connectedness, such an essence is usually associated with logistics (), production (; ; ), technological development (), services (), and collective consumption (). A contextual perspective on such development has been articulated in the form of the world city hypothesis and global city theorizations (; ).

Regarding the recent developments that have reshaped these urban functions, dramatic changes took place in post-war decades, which witnessed economic expansion, Keynesian economic policy, the emergence of influential social movements, and the rise of the welfare state. Further changes took place in the 1990s due to the intertwining of globalization and an emergent information society, which appeared to be game changers in many respects. Keynesianism made way for neoliberal policies, the fall of the Berlin Wall epitomized the collapse of socialism, and the crisis of the welfare state prompted a search for alternative models for organizing the economy and society. For some time, it looked as if the Western liberal democracy and its underlying capitalist economic system had won the ideological war ().

A range of factors started to shake the global scene and increase tensions in the West during the 2000s. Namely, the triumph of neoliberal thinking seemed to have been accompanied by continuous economic crises, such as the dot-com bubble of 2000, the financial crisis of 2007, the late-2000s recession, and the EU sovereign debt crisis 2009, to name a few. Other features included the accelerated intensity of the impact of global economic forces, the financialization of the economy, and the emergence of the so-called “new economy.” This had both positive and negative implications. Globally, millions of people were lifted from extreme poverty, especially after the opening of the economies of China and India in the late 1980s, but due to the consequent shift in production and services from developed to developing countries, unemployment and uncertainty increased in the West. In the urban world, the 1980s witnessed the emergence of neoliberal urbanism, which was expected to be the answer to the challenges posed by global competition. This was the time of the rise of urban entrepreneurialism (), in which local politicians, public managers and urban developers started to align the urban growth machine with the requirements of the global age ().

The neoliberal city epitomizes this development (; ; ). It emerged in the wake of the conservative and libertarian thinking in politics and society associated with economic liberalization and the promotion of free-market capitalism. Neoliberalism favors such policy measures and practices as dismantling trade barriers, privatization, competitive tendering, reductions in government spending, tax cuts, and consumer choice. In the management of cities, this led to the widespread adoption of the New Public Management (NPM) doctrine with its emphasis on marketization, managerialism, and customer choice (; ), on the one hand, and a competition-oriented development policy or urban entrepreneurialism, on the other (). The many faces of neoliberal urban policy are epitomized by such cities and city-states as New York, Chicago, Toronto, London, Frankfurt, São Paulo, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Shanghai.

Neoliberal thinking obviously reflects its liberal foundation, with roots in individual freedom. In urban life it has increased cost-awareness and competitiveness and contributed significantly to economic growth. However, it also has a negative effect that will be taken as the starting point of this chapter, namely in terms of social consequences. There are societal mechanisms that are supposed to bring about collective benefits from the full-fledged economic freedom of individuals. These include the “trickle-down” effect, “voting with one’s feet,” consumer choice, and the like. Yet, due to a variety of reasons, the aggregate impact of neoliberal policy seems to produce unintended consequences and side effects that cannot be ignored, especially when considered from the point of view of collective welfare and the fundamental conditions of human relations and existence. One critical aspect of this development is the so-called “great decoupling” in which, despite productivity increases, a large segment of the population is excluded from the fruits of economic success (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014). This is related to the polarizing tendencies of the new economy (). A factor contributing to this is the gradual transition toward the greater role of value extraction in the economy (). Even if neoliberalism as such is not the only cause behind such problems in the economy, it appears to have contributed to increased inequality, urban poverty, economic exclusion, and deprivation. More importantly, neoliberal thinking provides insufficient tools for understanding the nature of the social consequences of global and national free-market policies, and is even less equipped to produce the means to tackle them. Taken to the level of urban governance, this implies that urban boosterism and streamlined competitiveness policies may not provide the answers to the fundamental problems faced by cities. It could be hypothesized that we need more balanced perspectives, reinterpretations, and refocusings in order to meet such daunting challenges.

In this chapter, we will address this issue by discussing alternative views of economic growth and their implications for urban policy and governance.

From GDP to Well-Being

The conventional idea of economic growth is based on the implicit premise of most of the classic theories of urban growth and development that population and economy are typical indicators of urban growth. Let us begin with population.

Population growth as a global phenomenon has become a threat to sustainability. It is unevenly spread across the globe and produces huge economic inequalities between individual countries and locations. Interestingly, many developed countries have actually reached a point where their population is shrinking which, accompanied by the problems of a shrinking economy, has shifted the agenda from growth to shrinkage. For a long time, industrialization helped strategically well-positioned, advantageously located, and resourceful cities grow. There were undoubtedly declining areas too, but they were seen as exceptional, unlucky, or strategically incapable rather than as symptoms of a structural asymmetry. In the current situation many developed countries are entering a new phase in which the population is both aging and shrinking when migration is not considered. The challenge is that many countries are entering an era of shrinkage in all urban areas, as seen prominently in the case of Japan and a few other locations in Asia. While most Asian countries still experience stable economic growth, rapid aging and population decline are looming just around the corner and will eventually have an enormous societal impact, especially in the case of highly urbanized countries.

The previously discussed demographic trend has an equivalent in the economic life cycle as well. This is most relevant in urban economies, which have been very concerned with creating the preconditions for economic growth while treating citizens' well-being as a secondary matter. Approaches have been slightly more sensitive to context in political science and public administration, not to mention sociology and anthropology. However, it seems that irrespective of discipline, synthesizing views on the generative interplay of the economy and society have been rare. In addition, in most contributions the primary reference is still to urbanization, even if there is an obvious need to redirect the discussion to multi-dimensionality and the qualitative aspects of urban life. This becomes evident when discussing the conceptualization of urban decline, growth, and development.

Let us consider the following. When visiting a city, we sense its character, or as we may put it, its spirit or soul, which cannot be reduced to its population or economic scale or expansion. Rather, cities evince an important qualitative factor that resonates with something essentially human. Such qualitative aspects of the perception of cities give hope for shrinking cities. No matter how small the city is, it can focus on qualitative development. More importantly, this shift is not limited to shrinking cities, but reflects a need for a deeper reassessment of our perspective on urban development. In addition to an increased focus on the qualitative aspects of development, there is a need to pay attention to the distribution of the benefits from these development efforts. Growth should be smart and inclusive in order to increase the well-being of all members of the community. A precondition for this is that local and national policies support such a holistic and inclusive view of urban development.

One indication of such a paradigm shift is increased interest in happiness as a core element of well-being. Especially since the early 2000s, academics have started to examine how economic indicators relate to people's sense of well-being (; ) and how governments could use such data in a variety of policy areas to improve their citizens' quality of life (). Important steps were taken in 2008 when Nicolas Sarkozy, former President of France, called on economists Joseph E. Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, and Jean-Paul Fitoussi to set up the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. In 2010, the committee published a report titled Mismeasuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn't Add Up, which proposed three approaches to measure quality of life: (a) subjective well-being, i.e., understanding the determinants of quality of life at the individual level, (b) a capability approach for understanding the factors that expand life opportunities and options (health, education, income, etc.), and (c) fair allocations that reflect people’s preferences regarding various aspects of the quality of life. Through these, the Commission advocated the importance of understanding the non-monetary aspects of quality of life, such as health, education, social ties, environment, and safety ().

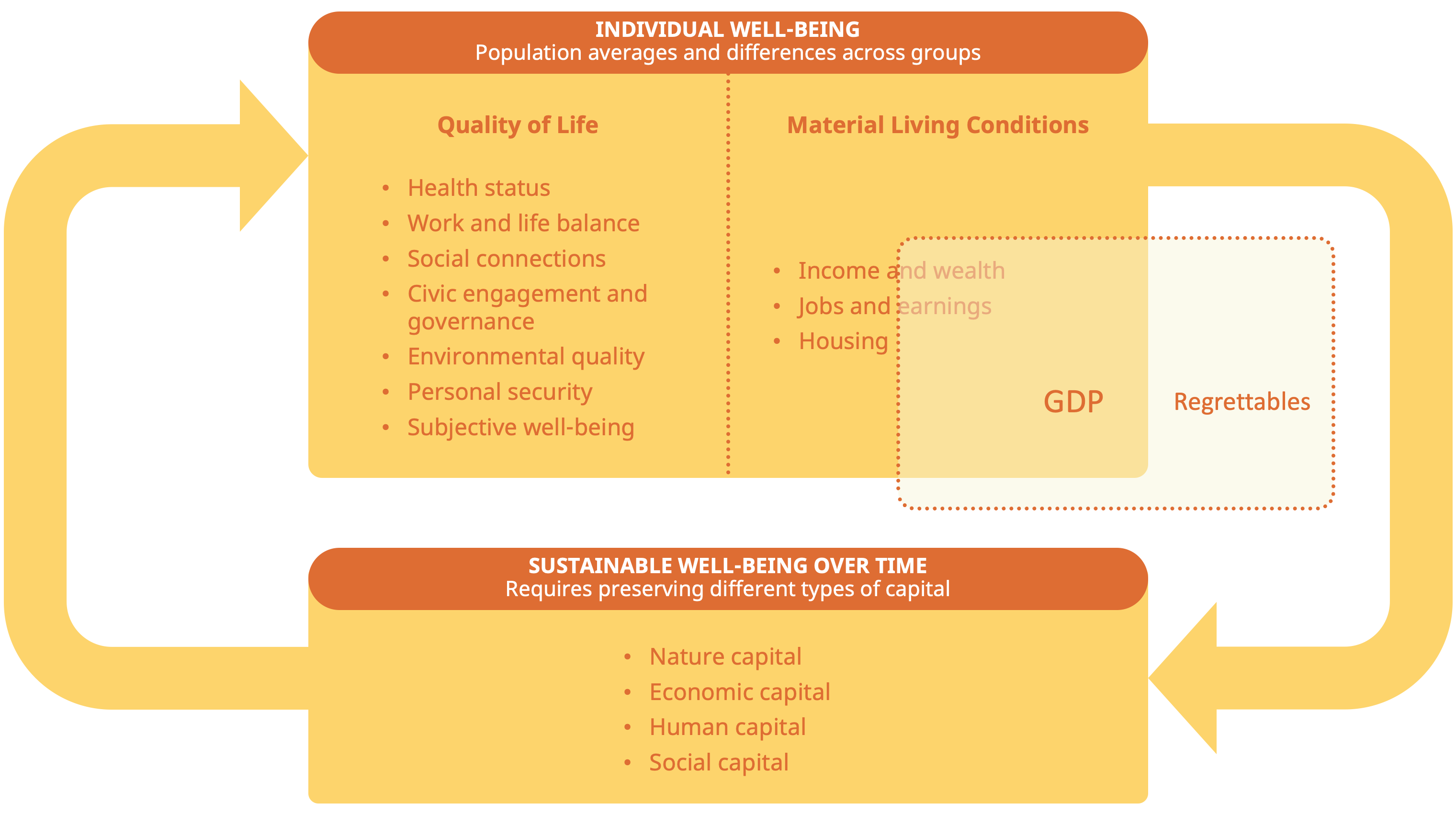

In response to this, the OECD developed the Better Life Index (see https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/), which lists 11 areas as indicators of personal well-being, grouped into two rather conventional main categories, “Quality of Life” and “Material Living Conditions” (see Fig. 2.1) ().

Although the indicators included in the “Quality of Life” category are not directly related to the economy, they are essential in determining and governing people's well-being. In addition, the OECD identified four categories of capital—natural, economic, human, and social—as the critical resources needed to sustain personal well-being. These are equivalent to such fundamental categories as nature, economy, individuals, and communities, which points to the contextual and holistic nature of human well-being.

The heightened interest in well-being and happiness provides a fresh view that challenges conventional conceptions of urban development. Most strikingly, it challenges the perception of economic growth as being the sole or the most important policy goal of city governments or as a privileged criterion for measuring success in urban development. Human and social factors thus have a vital role in the urban agenda, and social sciences and urban studies have an important task in shedding light on them and integrating them with other aspects into a holistically understood development agenda.

Policymaking for Urban Well-Being

A few decades after World War II, interest turned to the promotion of industrial development and amplified economic and population growth as a premise for such a policy. A crucial factor behind this development was the fact that major indicators on urban economic development had been primarily quantitative, which inherently directed attention to activities that were reflected in such indicators. Such a narrow approach tends to keep the urban development agenda instrumentalist and one-dimensional. This is noticeable in the case of the shrinking cities previously discussed, which have started to build their development agendas on novel premises as a reflection of changes in their internal and external environments. They have done so by understanding that shrinkage does not equal decline and recognizing that there are important qualitative aspects of development that should be taken into account. In this setting, the previously discussed role of well-being is critical, as it hints at what kinds of premises the new urban development paradigm can be built on, both as an element of endogenous growth and as a factor that has the potential to attract capital, expertise, creativity, and people to the city (cf. ).

examined in a multiple case study the push and pull factors that affect residents of shrinking cities in Portugal. According to them, the overall picture shows that, while economic conditions (job opportunities and good working conditions) are the most important factors (especially among the younger generation), social ties and place attachments significantly impact residents' decisions regarding migration. The study points out that stronger a sense of community and a city's identity increase the resilience of the city. It is worth mentioning that in some historical cities in Portugal, “beauty and heritage” was the most important pull factor affecting the decisions of residents. Furthermore, the influence of environmental factors such as “recreational and environmental amenities” was noticeable. Lastly, the study revealed that the factors that contributed significantly to the well-being of residents varied between cities.

has shown that people's evaluation of neighborhood quality is almost the same regardless of whether the city is growing or shrinking. In fact, from the point of view of smart growth, depopulation may occasionally be considered a strength. Along these lines, stated that, in shrinking cities, the neighborhood and social ties are strengthened and the relationships of trust between the residents are reinforced, leading to strengthened self-efficacy and collective efficacy. This hints that there is parallel between the strengthening of independence at the individual level and increasing social capital at the community level, which together serve as a positive force in shrinking cities.

Based on the evidence and insights discussed so far, we may conclude that it will be important for cities to design policies that consciously promote community capital, strengthen independence, and encourage place attachment. Such an approach combines different spheres of community life, including the physical environment, relational social capital, and urban symbolism ultimately geared around the well-being of urban dwellers.

Public Value Governance in Cities

Discussions about how to assess and value economic growth vs. well-being in public policy are deeply rooted in the ideological landscape. Focus on economic growth, especially in the Western context, is associated with neoliberalism, whereas an emphasis of holistic and inclusive well-being leans towards progressive and collectivist ideologies. Rather than taking sides in this debate, our task is to point to the relevance of discussing the values on which urban public policies can be based. In fact, if we look at urban issues from an ideological point of view along the lines of a conventional liberal vs. conservative dichotomy, it reveals the need to determine on a case-by-case basis what combination of values best suits each respective urban community. In any case, there is a growing need to clarify the values on which urban public policies should be anchored, which would benefit from broadening the perspective on urban development from a focus on mere monetary value (or economic growth) to a broader set of value categories, including well-being and happiness.

Capitalism is from the historical view a superior economic system in terms of organizing production and matching supply and demand. However, on the other side of the picture there are dysfunctional tendencies and socially polarizing outcomes that must be addressed in public policy. For example, has recognized that in modern capitalism, value-extraction is rewarded more generously than value-creation, even if the latter comprises the productive processes that essentially drive a healthy economy. She urges us to rethink capitalism, to redefine how to measure value in a society, and to rehabilitate the public sector as a key player in balancing such a development.

One of the most worrisome features of the global economy has been economic polarization. In advanced economies, top earners have experienced rapid income growth while the middle class shrinks and the lowest earners are left behind. This development is particularly striking in the United States (; ). These kinds of changes have made traditional economic indicators, such as GDP, look problematic, if not obsolete. Polarization implies that the economic benefits of the increase in GDP are reaped primarily by the wealthiest segment of society, or rather, the transnational capitalist class. This urges us to reconsider the relevance of traditional economic indicators as the measure of success ().

Measuring well-being, quality of life, or happiness has obvious challenges. Even if we use surrogate indicators and develop as many objective criteria as possible for determining such phenomena (e.g., aggregated holistic health data), the dilemma of subjective value and its methodological ramifications persists. A similar challenge to be faced is the multi-dimensionality of well-being, which makes this field conceptually fuzzy (see ). This should not prevent us from seeking measures of a good life beyond quantitative indicators. Many attempts have already been made. For example, proposed seven essentially irreplaceable values for living a good life, namely health, security, respect, personality, harmony with nature, friendship, and leisure.

Another strand of thought that offers conceptual tools to deal with the challenge at hand is public value theory, which emerged in the 1990s (). This discourse is of particular interest here because it shows how the concept of value is used in public administration, management, and policy. The original idea proposed by was based on public managers' ability to create value in a society by using the means available to the government, such as service machinery, regulations, laws, resource allocation, and others. This is based on an idea that legitimizes the existence of government: government should be able to create value in a society in collaboration with a wide range of stakeholders from different sectors.

A watershed moment in this discourse becomes apparent when we consider what “public” actually refers to in this context, and what is the factual role of government in creating public value or ensuring that public interest is taken into account in all relevant aspects of community life. The minimum criteria for anything to be “public” are (a) collective or democratic decision-making, (b) community involvement in policy making, governance or management, and (c) public funding. So, for any activity to be deemed “public” in the given context it should fulfil these three criteria. When government is involved in creating public value, it is expected to base its actions both on collective values—e.g., fairness, equality, and social cohesion—as explicated in policy or legislative documents, and on the principles of good governance, including participation, effectiveness, responsiveness, transparency, and accountability. It is generally held that the impact of private-sector management doctrines and the New Public Management in particular have in fact diminished the “publicness” of public administration (Rugge, 2019).

The discussion of public value is rather government-centric and, to some extent, public-management-oriented. It is important to keep in mind that all individuals, organizations, and institutions create or at least have the potential to create public value irrespective of the degree of their publicness. This gave rise to new public governance, new public service, network governance, and public value management approaches that brought values to the core of public governance and public-sector management. Especially, early developments surrounding public value management in the public sector became associated with networked governance methods that focus on the motivational side of stakeholder engagement, including loyalty, mutual respect, shared learning, and negotiated order (). This is seen as an approach built on values that go beyond efficiency, giving prominence to the application of democratic principles. Government serves as a collectively organized guarantor of the creation of public value, but it is worth emphasizing that the government does not have a monopoly on the agenda setting, public debate, and value-driven practices found in society because citizens, civic associations, and businesses have their stakes in such collective processes too ().

The public value perspective emphasizes the active role local civil society and the business community have in open discussions about the values and guiding principles applied both in the public sphere and in, partly, the private sphere in the community. This requires enabling community structures, such as open policy forums, deliberative mechanisms, and urban public spaces, as well as fostering a culture of openness and inclusion that encourages communicative action. It is important that, in addition to formal political institutions, there are informal arrangements, public spaces, cafeterias, parks, shopping districts, and other “third places” suitable for interaction and exchange of ideas (; ; ). We need to consider as well the use of digital technology, social media, and urban networks and platforms, many of which are locally embedded. A strategically critical mission is to integrate such civic discourses, forums, and platforms into the decision-making procedures of the city government in a dynamic and flexible manner. This integration requires a generative interplay between an unorganized discursive sphere and a democratically controlled decision sphere.

From Theory to Practice

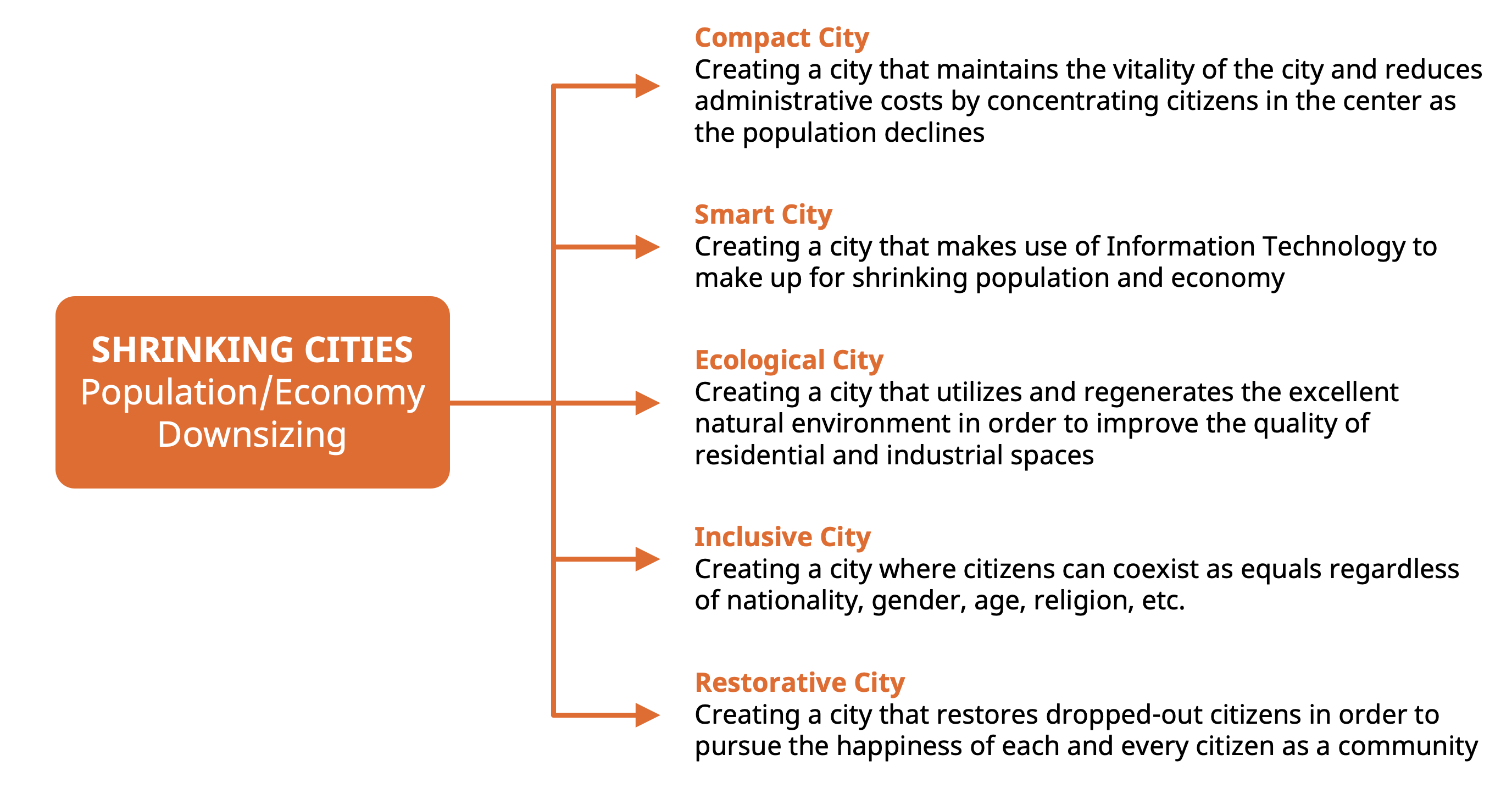

There are already many cities all over the world that reflect an alternative view on growth and pay special attention to the well-being of citizens. There are zero-carbon communities that aim for hands-on sustainability, wellness cities with a focus on holistic health, slow cities (like the Cittaslow Movement) designed to improve quality of life, shelter cities that pay special attention to human rights, and others. It is worth noting that there are many ways of promoting well-being and quality of life. For example, as in the case of the shrinking cities previously discussed, they can adopt various strategies for responding to their contextual challenges, as depicted in Fig. 2.2.

When discussing cities with progressive policies that broaden the view of urban development, this book will address such cases both theoretically and empirically. These include city-concepts such as smart, compact, shrinking, sustainable, restorative, and inclusive cities, each reflecting particular aspects of urban well-being. One of the main policy challenges faced by cities is to be able to take a holistic view of urban development and thus to be able to pinpoint the interrelatedness of the environment, people, technology, and economic development. The path towards urban futures should be sustainable, democratic, smart, and inclusive, as these qualities are conducive to a genuinely citizen-centric approach to urban development that is able to contribute to the holistic health, well-being, and happiness of the citizenry.

Bibliography

- Anttiroiko, 2018

- Anttiroiko, A.-V. (2018). Wellness City: Health and Well-Being in Urban Economic Development. Cham: Palgrave Pivot.

- Anttiroiko et al., 2020

- Anttiroiko, A.-V., Laine, M., & Lönnqvist, H. (2020). City as a Growth Platform: Responses of the Cities of Helsinki Metropolitan Area to Global Digital Economy. Urban Science, 4, article 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci4040067

- Bhatt et al., 2020

- Bhatt, A., Kolb, M., & Ward, O. (2020). How to Fix Economic Inequality? An Overview of Policies for the United States and Other High-Income Economies. Peterson Institute for International Economics. Retrieved September 14, 2021, from https://www.piie.com/microsites/how-fix-economic-inequality#group-Intro-dc0T90OR22

- Bok, 2010

- Bok, D. (2010). The Politics of Happiness: What Government Can Learn from the New Research on Well-Being. Princeton University Press.

- Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014

- Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014). The Second Machine age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. New York: WW Norton & Company.

- Bryson et al., 2014

- Bryson, J.M., Crosby, B.C., & Bloomberg, L. (2014). Public Value Governance: Moving beyond Traditional Public Administration and the New Public Management. Public Administration Review, 74(4), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12238

- Cardenas et al., 2017

- Cardenas, I., Borbon-Galvez, Y., Verlinden, T., Van de Voorde, E., Vanelslander, T., & Dewulf, W. (2017). City logistics, urban goods distribution and last mile delivery and collection. Competition and Regulation in Network Industries, 18(1-2), 22-43. https://doi.org/[10.1177/1783591717736505](https://doi.org/10.1177/1783591717736505)

- Castells, 1977

- Castells, M. (1977). The Urban Question: A Marxist Approach. From La question urbaine (1972, 1976) translated by Alan Sheridan. Edward Arnold.

- Castells & Hall, 1994

- Castells, M. & Hall, P. (1994). Technopoles of the World: The making of twenty-first-century industrial complexes. Routledge.

- Easterlin, 2001

- Easterlin, R. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. Economic Journal, 111, 465–484.

- Fox, 2012

- Fox, J. (2012). The economics of well-being. Harvard Business Review, 90(1-2), 78–83, 152.

- Frey & Stutzer, 2001

- Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (2001). Happiness and Economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Friedmann, 1986

- Friedmann, J. (1986). The World City Hypothesis. Development and Change, 17(1), 69-83.

- Fukuyama, 1989

- Fukuyama, F. (1989). The End of History? The National Interest, 16, 3–18.

- Guimarães et al. (2016)

- Guimarães, M.H., Catela Nunes, L., Barreira, A.P., & Panagopoulos, T. (2016). What makes people stay in or leave shrinking cities? An empirical study from Portugal. European Planning Studies, 24(9), 1634–1708.

- Habermas, 1991

- Habermas, J. (1991). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Polity.

- Hackworth, 2007

- Hackworth, J. (2007). The Neoliberal City: Governance, Ideology, and Development in American Urbanism. Cornell University Press.

- Harvey, 1989

- Harvey, D. (1989). From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism. Geografiska Annaler, B, 71(1), 3–17.

- Helper et al., 2012

- Helper, S., Krueger, T., & Wial, H. (2012) Locating American Manufacturing: Trends in the Geography of Production. Washington DC: The Brookings Institute. Retrieved September 16, 2021, from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/0509_locating_american_manufacturing_report.pdf

- Henderson et al., 1995

- Henderson, V., Kuncoro, A., & Turner, M. (1995). Industrial Development in Cities. Journal of Political Economy, 103(5), 1067–1090.

- Hollander (2011)

- Hollander, J.B. (2011). Can a City Successfully Shrink? Evidence from Survey Data on Neighborhood Quality. Urban Affairs Review, 47(1), 129–141.

- Hood, 1991

- Hood, C. (1991). A Public Management for All Seasons?. Public Administration, 69(Spring), 3-19

- Jones et al., 2014

- Jones, H., Cummings, C., & Nixon, H. (2014). Services in the city: Governance and political economy in urban service delivery. ODI Discussion Paper, December 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2021, from https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/9382.pdf

- Knafo, 2020

- Knafo, S. (2020). Neoliberalism and the origins of public management. Review of International Political Economy, 27(4), 780–801.

- Kotkin, 2005

- Kotkin, J. (2005). The City: A Global History. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Llena-Nozal et al., 2019

- Llena-Nozal, A., Martin, N., & Murtin, F. (2019). The economy of well-being: Creating opportunities for people’s well-being and economic growth. OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2019/02. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/498e9bc7-en.

- Lobo et al., 2013

- Lobo J., Bettencourt, L.M.A., Strumsky, D., & West, G.B. (2013). Urban Scaling and the Production Function for Cities. PLoS ONE, 8(3), e58407. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058407

- Mazzucato, 2018

- Mazzucato, M. (2018). The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy. Public Affairs.

- Moore, 1995

- Moore, M. (1995). Creating public value: strategic management in government. Harvard University Press.

- Oldenburg, 1989

- Oldenburg, R. (1989). The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You Through the Day. Paragon House.

- Pinson & Morel Journel, 2016

- Pinson, G., & Morel Journel, C. (2016). The Neoliberal City – Theory, Evidence, Debates. Territory, Politics, Governance, 4(2), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2016.1166982

- Sandel, 1996

- Sandel, M. (1996). Democracy's Discontent. Belknap Press.

- Sassen, 2001

- Sassen, S. (2001). The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1991)

- Skidelsky and Skidelsky (2013)

- Skidelsky, R.J.A., & Skidelsky, E. (2012). How Much Is Enough?: Money and The Good Life. Allen Lane.

- Stiglitz et al., 2010

- Stiglitz, J.E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2010). Mismeasuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn't Add Up. The New Press.

- Stoker, 2006

- Stoker, G. (2006). Public Value Management: A New Narrative for Networked Governance? The American Review of Public Administration, 36(1), 41–57.

- Storper, 2016

- Storper, M. (2016). The neoliberal city as idea and reality. Territory, Politics, Governance, 4(2), 241–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2016.1158662

- van der Land and Doff (2010)

- van der Land, M., & Doff, W. (2010). Voice, exit and efficacy: dealing with perceived neighbourhood decline without moving out. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25, 429–445.