4. Practices of Japanese Local Cities Coping with Population Decline

- Kiyonobu Kaido, Professor Emeritus, Meijo University (Japan)

- Keiro Hattori, Professor, Faculty of Policy Science, Ryukoku University (Japan)

- Yasuyuki Fujii, Professor, Faculty of Cultural Policy and Management, Shizuoka University of Art and Culture (Japan)

- Mihoko Matsuyuki, Professor, Institute of Urban Innovation, Yokohama National University (Japan)

- Tomohiko Yoshida, Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, Ritsumeikan University (Japan)

Introduction

The population of Japan reached its peak in 2008 and has declined continuously since then. According to the Basic Resident Register, the population of Japan declined by approximately 0.8% from 2014 to 2019. The main reason for this population decline is a natural decrease in population (hereafter referred to as “the natural decrease”). Even in the 1960s, some municipalities experienced population outflow. The main reason for this population outflow was migratory population loss (hereafter referred to as “net migration loss”). Therefore, population decline, which many municipalities in Japan have experienced in recent years, can be understood as a social phenomenon that differs from the decline seen in the past.

It is extremely difficult to prevent the natural decrease through urban and regional policies, as these policies can take more than 25 years to show their effects after being initiated. As the historical demographist Kitou () pointed out, “population change takes quite a long time, similar to the turnaround of a huge tanker.” However, certain policies can prevent net migration loss to some extent. These policies are directly effective for mitigating population decline. Although the overall population of Japan has decreased, the population of several big cities has continuously increased at the same time. Therefore, a population shift from these big cities to other areas where the population has decreased is considered to be in conformity with national strategy.

In the global context, Mallach et al. () organized the discussion on shrinking cities as a conceptual model organized around “conditions,” “scholarly discourses,” and “policy and action.” They concluded that it was important to identify the existence of conditions adequate to create the “political will” necessary to address the shrinking city’s problems. A key characteristic of the Mallach’s model is that it is oriented toward action. The authors recognized that the nature of the shrinking city problem needed to be redefined for purposes of action as a specific and narrow issue because policy is not always generic. Martinez-Fernandez () defines three areas that are commonly needed to tackle the worldwide decline of population in Europe, Australia, Japan, and the U.S. in terms of policy processes like community resilience, urban regeneration strategies, and tackling the social effects of urban shrinkage. As was the case in these previous studies, the present authors also pay attention to the social aspects of population decline.

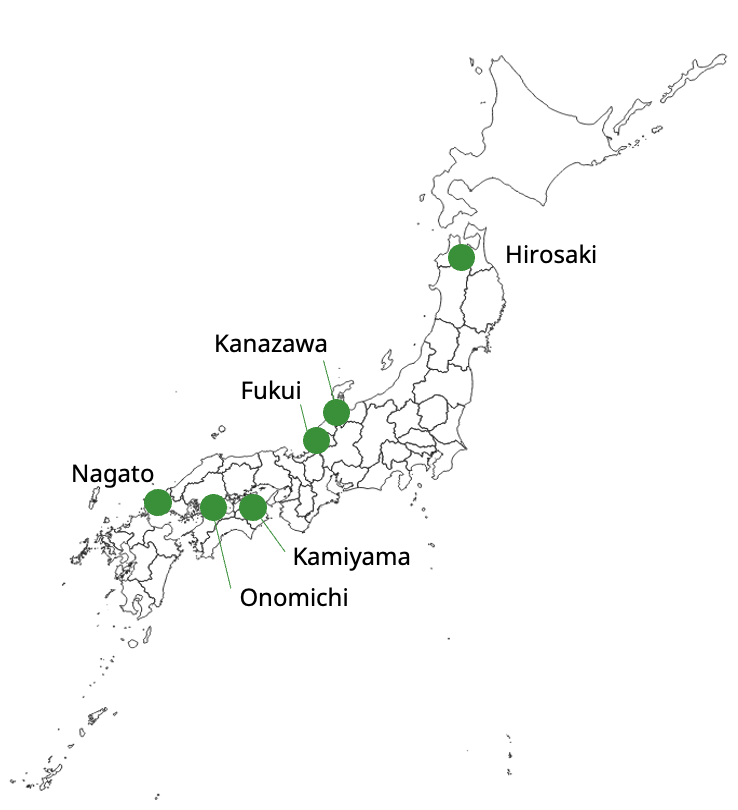

The present authors examined municipalities with a population below 500,000 that had enacted policies considered to be effective for preventing net migration loss (policies to decrease the number of people flowing out and increase the number of people flowing in), performed on-site investigations of specific policies and trends in the private sector, and summarized the investigation results. These cases address the six municipalities of Kanazawa (Ishikawa Prefecture), Hirosaki (Aomori Prefecture), Fukui (Fukui Prefecture), Onomichi (Hiroshima Prefecture), Nagato (Yamaguchi Prefecture), and Kamiyama (Tokushima Prefecture).

Table 4.1: Natural increase or decrease and net migration gain or loss of municipalities investigated from 2014 to 2019

| Prefecture name | Municipality name | Population (2019) | Population (2014) | Percent change | Natural increase or decrease | Net migration gain or loss | Contribution ratio of the net migration loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aomori Prefecture | Hirosaki City | 172,031 | 180,370 | -4.6% | -6,665 | -3,175 | 0.32 |

| Aomori Prefecture | Aomori City | 284,531 | 298,416 | -4.7% | -9,590 | -6,671 | 0.41 |

| Ishikawa Prefecture | Kanazawa City | 453,654 | 452,144 | 0.3% | -2,937 | 4,812 | 2.57 |

| Fukui Prefecture | Fukui City | 264,356 | 267,978 | -1.4% | -3,581 | -685 | 0.16 |

| Hiroshima Prefecture | Onomichi City | 137,643 | 144,935 | -5.0% | -7,011 | -1,972 | 0.22 |

| Yamaguchi Prefecture | Nagato City | 34,305 | 37,384 | -8.2% | -2,823 | -902 | 0.24 |

| Tokushima Prefecture | Kamiyama Town | 5,319 | 6,128 | -13.2% | -719 | -263 | 0.27 |

| Population between 200,000 and 500,000 | 0.1% | -243,723 | 269,898 | 10.31 | |||

| Same as above, excluding three metropolitan areas | -1.4% | -258,294 | 100,560 | -0.64 | |||

| Population between 80,000 and 200,000 | -1.0% | -397,693 | 26,731 | -0.09 | |||

| Same as above, excluding three metropolitan areas | -2.3% | -325,777 | -125,706 | 0.35 | |||

| Population between 10,000 and 50,000 | -4.9% | -684,438 | -333,994 | 0.37 | |||

| Population between below 10,000 | -7.8% | -169,468 | -88,811 | 0.42 |

Source: Created by the authors, etc. based on the Basic Resident Register

Study Background: Population Changes in Municipalities in Terms of “Net Migration Gain or Loss”

Table 4.1 shows the population changes, natural increases or decreases, and net migration gains or losses in municipalities investigated from 2014 to 2019, along with the averages of these figures according to the population category. The populations of municipalities with populations between 200,000 and 500,000 slightly increased (by 0.1%) from 2014 to 2019 because the net migration gain was slightly larger than the natural decrease. However, the total population of municipalities excluding three major metropolitan areas (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, and Saitama Prefectures in the Kanto area, Osaka, Hyogo, and Kyoto in the Kansai area, and Aichi Prefecture), decreased by 1.4%. This is because the natural decrease was approximately 2.5 times the net migration gain in these municipalities, although a natural increase was observed.

During the same period, the rate of population decline in municipalities with populations between 80,000 and 200,000 was 1%. The reason for this population decline is that the natural decrease was 14.9 times the net migration gain in these municipalities. The net migration loss was also observed in municipalities when the three metropolitan areas were excluded. However, the contribution ratio of the net migration loss to the population decline was approximately 35%. The rate of population decline among municipalities with populations between 10,000 and 50,000 was 4.9%, and the contribution ratio of the net migration loss to the population decline was 37%. The rate of population decline of municipalities with populations of <10,000 was 7.8%, and the contribution ratio of the net migration loss to the population decline was 42%. The population decline rate increased as the population decreased. Both the natural decrease as well as the net migration loss intensified as the population decreased. In what follows, the authors discuss the characteristics of core cities in local urban areas and peripheral small towns of the core cities. Kanazawa, Fukui, and Hirosaki are defined as the core cities (having populations between 200,000 and 500,000). Onomichi, Kamiyama, and Nagato are defined as peripheral small towns (having populations less than 200,000).

Core Cities in the Local Urban Areas

Kanazawa: Net Migration Gain as a Result of Gentrification

Compared to municipalities in the same population category (between 200,000 and 500,000 in Table 4.1), excluding the three metropolitan areas, the population growth rate of Kanazawa was higher. Furthermore, the net migration gain was larger than the natural decrease in Kanazawa.

Kanazawa is the capital of Ishikawa Prefecture, boasting a population slightly more than 450,000 in 2019. Kanazawa initially grew as a temple town around the Oyama-Gobo Temple and then flourished as the castle town of the Kaga Domain ruled by the Maeda family. As Kanazawa managed to escape strategic bombing during World War II and other great disasters, the streetscape of the Edo period (1603‒1868) remains in place even in the modern era. The population of Kanazawa already exceeded 100,000 in the Edo period. During the late Edo period, Kanazawa developed as a large city alongside the three capitals of Edo (Edo is an old name of Tokyo at the present), Osaka, Kyoto, and Nagoya. After the Meiji Restoration (1868), as cities facing the Pacific Ocean began to rapidly develop, Kanazawa lagged behind Kobe and Yokohama. After World War II, Toyama and Komatsu (which are located in the vicinity of Kanazawa) developed due to the growth of the manufacturing and chemical industries. Although manufacturing companies such as Tsudakoma Corp. and I-O Data Device, Inc., are located in Kanazawa, many people there are generally engaged in commerce and tourism. Thus, Kanazawa has developed as a consumption-centered city.

Although the population of Kanazawa decreased immediately after the Meiji Restoration, it has gradually increased since then. However, the population growth rate of Kanazawa was not very high compared with that of other local central cities. The population of Kanazawa exceeded 450,000 in 1995 and has remained largely stagnant since then. The population of Kanazawa in 2019 was 453,654. During nine recent years (2010–2019), the natural decrease was approximately 1% and the net migration gain was approximately 2%. Therefore, the net migration gain tended to compensate for the natural decrease. In Kanazawa before 1995, the natural increase tended to compensate for the net migration loss. After 2008, the net migration gain was larger than the natural decrease. After 2012, the natural decrease was larger than the net migration gain. Thus, the population dynamics of Kanazawa changed markedly after 2010.

The Hokuriku Shinkansen, a high-speed bullet train railway line, has facilitated the net migration gain. Kanazawa Station on the Hokuriku Shinkansen line opened in March 2015. According to a report by the Development Bank of Japan, the economic ripple effect of the Hokuriku Shinkansen on Ishikawa Prefecture was approximately 67.8 billion yen, which was markedly larger than what was predicted before the opening of the station (12.4 billion yen). Due to this economic impact, issues of gentrification have arisen in the urban district. Following the opening of Kanazawa Station on the Hokuriku Shinkansen line, increases in the home values in Kanazawa have been much larger than those of other cities in Japan, and the numbers of new offices and stores have increased. This marked increase in tourism demand has also prompted hotel-related investments.

These trends have led to the conservation of many traditional town houses (wooden buildings built before 1950) in Kanazawa through the establishment of new regulations. Although townhouses in Kanazawa are valuable urban resources, people in Kanazawa tend to avoid such houses because they are said to be “old, dark, and cold.” With the widespread demolition of these townhouses in Kanazawa, their numbers have decreased. As a policy to promote the use of townhouses in response to the needs of a new era while simultaneously conserving the structures, Kanazawa established the “regulations on promoting the conservation and utilization of Kanazawa town houses” in 2013 before the opening of Kanazawa Station on the Hokuriku Shinkansen line. Approximately 6,100 townhouses existed in Kanazawa when the regulations were established; however, 550 were lost within five years. Thus, the demolition of townhouses has continued in Kanazawa. Fortunately, there are several cases where the conservation and utilization of townhouses that can be considered model cases. Examples include Yaoyoroz Honpo, a multipurpose store opened in March 2015, HATCHI Kanazawa, a hotel opened in March 2016, and KUMU, a multipurpose hotel opened in August 2017. Following these pioneer cases, townhouses have been renovated into residences, restaurants, cafes, stores, galleries, studios, and guest houses. Thus, a new twist on old charm has been generated in the central urban area of Kanazawa.

Among the 35 prefectural capitals, excluding ordinance-designated cities, the population increased in only 11 from 2010 to 2019 (excluding Matsue, which merged cities, towns, and villages). Of these 11 cities, a natural increase was observed only in six. In contrast, a net migration gain was observed in 25 cities. In Kanazawa, the net migration gain has compensated for the natural decrease, and its population has been maintained. However, this compensation results in gentrification. Therefore, a policy to positively conserve urban resources, such as townhouses, is required. Although Kanazawa belongs to the group of cities exhibiting a net migration gain in the era of depopulation, Kanazawa highlights the need for an urban policy that generates subtle solutions to thorny problems.

Fukui: Repair of Old Buildings and Young Business Persons

The rate of population decline of Fukui is similar to that of municipalities in the same population category (between 200,000 and 500,000), excluding the three metropolitan areas. Although municipalities in this population category exhibit a net migration gain on average, Fukui has shown a net migration loss. However, the number of people counted in the net migration loss is small, being much smaller than the losses incurred by cities on the Sea of Japan side of the country, such as Aomori, Akita, and Nagaoka, although the number of people counted as part of the net migration loss of Fukui is larger than that of cities in three prefectures in the Hokuriku region (Fukui, Ishikawa, and Toyama Prefectures).

Fukui is the capital of Fukui Prefecture. The population of Fukui is slightly more than 260,000 in 2019. Fukui developed as the castle town of the Echizen Domain ruled by Katsuie Shibata, a military commander in the age of civil strife. In the Edo period, Fukui became the central city of the Echizen Province, which yielded 680,000 koku of rice (1 koku ≈ 140‒150 kg). From the Meiji period (1868‒1912), Fukui flourished as one of Japan’s foremost textile cities. However, it suffered from strategic bombing during World War II, and the Fukui Earthquake occurred in 1948. Thus, Fukui was severely damaged. Since then, Fukui has performed reconstruction projects and been renewed like a phoenix. From 1971 to 1974, Fukui merged with the surrounding towns and villages, causing the area of Fukui to increase from 33 km2 to 339 km2. The population of Fukui also increased from 77,000 to 230,000, reaching its peak in 1995 and then beginning to decrease. In 2006, Fukui merged with the surrounding towns and villages again, causing its area to increase further. The population of Fukui significantly increased but then tended to decrease again, although the decrease was insignificant. The population of Fukui decreased by approximately 1% over nine years (2010–2019), decreasing by 0.1%–0.3% every year except for 2013. Although the natural decrease in these nine years was approximately 2%, the net migration gain in the same period was approximately 1%. Because the net migration gain partially compensated for the natural decrease, the population decline of Fukui tended to be eased to some extent.

Due to the two above-mentioned events (strategic bombing during World War II and the Fukui Earthquake in 1948), Fukui was heavily reconstructed. However, the road toward reconstruction taken by Fukui differed from that taken by many other cities that were also recovering from war damage. Based on the firmly-held city planning ideas of Tasaburo Kumagai, the Mayor of Fukui at that time, Fukui placed emphasis on the construction of road networks. As a result, the urban structure of Fukui was able to keep up with the subsequent progress of motorization to a certain extent.

However, by executing the above-mentioned city planning, the automobile dependency of Fukui increased; the number of owner-driven cars per household in Fukui Prefecture came to be the largest in Japan, suburbanization progressed, and consequently, the central district of Fukui began to deteriorate. In the 2000 census, the move-in ratio of population from 1995 to 2000 of Matsuoka Town (Eiheiji Town at present), which was adjacent to Fukui City, was the highest (8.1%) in Fukui Prefecture. The move-in ratio of the town previously known as Shimizu Town, which was merged into Fukui City, was 4.7%. Thus, the move-in ratios of municipalities in the suburbs of Fukui were high, highlighting the remarkable population outflow to the suburbs of Fukui in the late 1990s. As a result, the central district of Fukui deteriorated, the number of residents decreased, and vacant stores and parcels of land began to appear in the central district of Fukui.

To address these issues, Fukui has adopted policies to both encourage people to live in the central district and to attract customers. The placement of Fukui Station on the Hokuriku Shinkansen line, which will open in 2023, has facilitated these policies, and areas surrounding Fukui Station have already been redeveloped. In 2016, Happiring, a 21-story compound building, opened at the east exit of Fukui Station. In this building, the lower floors are used for commercial complexes, including a multipurpose hall and a planetarium, while higher floors are reserved for residences. Happiring is the highest building in Fukui Prefecture. On the east side of Happiring, a 27-story building is under construction. This building will house a large number of residences as well as commercial facilities, including a hotel. The number of people living in the central district of Fukui is thus predicted to increase in the future.

In addition to the above-mentioned large-scale developments, attempts to improve the charm of the central district have been implemented, including the adoption of a town-planning-like approach that promotes the repair of old buildings. For example, the floor space of wooden buildings over 60 years old accounts for 77% of the total floor space of buildings in a 0.8 ha area adjacent to Shinsakae Shopping Mall near Fukui Station (Fukui City as of 2013). Because the condition of this area is excellent, the implementation of an urban redevelopment project through an exchange of property rights system similar to that used in nearby areas, has been considered many times. However, no large-scale redevelopment project has yet been put into place because the ownership of property rights is extremely complicated. In cooperation with Harada Laboratory at the University of Fukui, Fukui investigated the intentions of property owners in the area in 2013. Based on the investigation results, a social experiment was performed. Consequently, a square called Shinsakae Terrace, in which wooden decks were laid on an outdoor parking lot, was installed. This square has been used for various events, leading to the development of a space in which a variety of people and organizations gather and interact with each other. A survey of visitors performed in 2015 revealed that approximately 90% of visitors felt that “the impression of the central area has improved for the better” and the number of vacant stores in the area adjacent to Shinsakae Shopping Mall began to decrease in 2015 (). Despite the presence of many old buildings in this area, we could find several young businesspeople who rented old vacant stores when we visited the site. Although the net migration gain is extremely small according to statistical analyses at present, the number of people from Fukui moving to cities in other prefectures is expected to decrease thanks to the implementation of urban regeneration projects for the central district of Fukui in the form of structural measures such as constructing new buildings, as well as non-structural measures such as renting out old stores.

Hirosaki: As a Case of City Center Residence

Compared to municipalities in the same population category (between 80,000 and 200,000), excluding the three metropolitan areas, the rate of population decline in Hirosaki was higher. The contribution ratio of the net migration loss to the population decline was also higher than the average. Compared to municipalities in three prefectures in the northern part of the Tohoku region on the Sea of Japan side of the country (Aomori, Akita, and Yamagata Prefectures), the rate of population decline of Hirosaki was the lowest, and the contribution ratio of the net migration loss to the population decline was the second-lowest, barely surpassed by Sakata. It is worth noting that the rate of population decline in Aomori was higher than that in Hirosaki and the contribution ratio of net migration loss to the population decline of Aomori was higher than that of Hirosaki. Aomori is the prefectural capital of Aomori Prefecture, and the population of Aomori (more than 200,000) is much larger than that of Hirosaki. The reasons why the rate of population decline of Hirosaki was lower than that of Aomori are examined below.

As mentioned above, compared to municipalities in the same population category (between 80,000 and 200,000), the population decline rate and contribution ratio of net migration loss of Hirosaki were higher. For this reason, it may not be appropriate to include Hirosaki as a case to be evaluated in this study, yet the population decline rate and the contribution ratio of the net migration loss in Hirosaki were relatively good for a city in the northern part of the Tohoku region on the Sea of Japan side, where the population decline has generally been quite rapid. Notably, the population decline in Hirosaki was smaller than that in Aomori. The correlation coefficient between the total population of 99 municipalities in three prefectures in the northern part of the Tohoku region on the Sea of Japan side and the population growth rate from 2010 to 2019 was 0.44. This value suggests that the population decline rate increased as the population decreased. However, the population decline rates of Aomori and Hirosaki in the same period were 6.5% and 6.4%, respectively. Furthermore, the net migration losses of Aomori and Hirosaki were 2.9% and 1.8%, respectively. Therefore, Hirosaki showed a greater ability to maintain its population level than Aomori even though the population of Hirosaki is approximately 60% that of Aomori. The reasons for the above-mentioned differences were examined on the assumption that differences in the urban policies between the two cities were involved.

We searched newspaper databases using “Aomori” and “compact city” as keywords and we found the first mention of the “compact city concept” advocated by Seizo Sasaki, the Mayor of Aomori in 1997. According to the article, Mayor Sasaki proposed the compact city concept in his 21st Century Creation Plan (1995), which was the new long-term master plan. This plan states that urban functions should be concentrated in areas surrounding Aomori Station and that the utilization of areas in front of the station is to be set aside for private initiatives. The Auga Building, which is located in front of Aomori Station and was constructed in the First-Class Urban Redevelopment Project and opened in 2001, became a symbol of this plan. The number of visitors temporarily exceeded six million per year, so the Auga Building sprang into fame as a successful case of the compact city concept. However, as reported in a newspaper article on a major portal site by Shouji (), Namioka Town was merged into Aomori City, Sasaki was rejected in the mayoral election, and many tenants moved out of the Auga Building. Before January 2018, Aomori City Hall was already using four floors (first to fourth floors) of the Auga Building for its functions, a situation that continues in the present. Therefore, Aomori City Hall took responsibility for the worsening of the management of the Auga Building. Aomori City Hall and local shopping streets are now looking toward a better future while returning to the concept of “city planning to allow people to live comfortably while considering job creation” (). From the perspective of business administration, Aomori has sufficient experience in the plan-do-check-act cycle, also known as the Shewhart Cycle. Therefore, Aomori can be considered the “pioneer of the compact city.”

When we searched academic papers using “Aomori” and “compact city” as keywords in Japanese, we found a study by Kaido () in J-STAGE, the largest database of academic papers in Japan. This study performed a correlation analysis between population density and accessibility to local community facilities using 49 cities in Japan to investigate the “paradox of the compact city,” which arose in Europe and America. The “paradox” in this case refers to a phenomenon in which a negative effects occur in a compact city due to overcrowding and congestion when its population density increases, resulting in a city becoming more inconvenient to navigate and live in as the city becomes more compact. Kaido () concluded that although population density was correlated with market orientation indices such as traffic networks and convenience store availability, it was not correlated with parks and meeting places. Therefore, a location policy for these public facilities was considered important. Along with Kanazawa, Fukui, and Akita, Aomori is considered to be a city of the Hokuriku and Tohoku regions, where dwelling house sizes are large and accessibility to public transportation facilities is considered acceptable. From this viewpoint, Aomori can be understood to be on the way back to embracing a “location policy for public facilities” () following its painful experience with the private project surrounding the Auga Building as handled by Aomori.

Hirosaki was the castle town of the Hirosaki Domain, the popular name of which is the Tsugaru Domain. The urban structure of Hirosaki has accepted “historical constraints” as discussed by Yokoo (). In 1896, during the second half of the Meiji period, the garrison of an army division that had jurisdiction over the northern part of the Tohoku region was located in Hirosaki. Since then, urbanization has made considerable progress. After World War II, the urban district of Hirosaki expanded, centering on the castle town and garrison. Core urban facilities, such as schools and hospitals, were built in places that had previously been used for military sites. The city area expanded at this point due to boundary changes. The main population growth spurt had already occurred between 1930 and 1945. The location of military sites is known to have markedly affected the urbanization process at that time (). Along with old towns on the outskirts of the town located in the northwest part of Hirosaki, the educational, medical, and welfare facilities located in the southeast part of Hirosaki are considered to have played a key role in the promotion of urbanization after World War II.

Aomori was established as a port town of the Hirosaki Domain. However, Hirosaki conspicuously exhibits the characteristics of a castle town or political center due to the history described above. In the past, Hirosaki was called Naka Tsugaru (central Tsugaru), Aomori was called Higashi Tsugaru (east Tsugaru), and Kuroishi was called Minami Tsugaru (south Tsugaru). The history of Hirosaki shows that Hirosaki sits at the center of the Tsugaru region, which is why a national university and national medical institution are located in Hirosaki.

When we searched academic papers using “Hirosaki” and “compact city” as keywords, similar to our process for Aomori, the oldest paper found was a study entitled “City Center Residence” published by Kitahara in 2003. Since then, Kitahara has published many studies on city center residences, repeatedly asserting that “the compact city cannot be simply realized by a policy to encourage people to move from detached houses in suburban residential areas to apartment houses in the central district” (). Kitahara is the first person to assert that the so-called compact city cannot be simply achieved through redevelopment projects in the central district and the relocation of dwellings from suburban residential areas. The conclusion that “the sustainability of a suburban residential area can only be examined based on the existence of an idea that the area should be mainly managed by its residents, and this examination will result in the realization of a true compact city” is particularly suggestive ().

One of the characteristics of the Location Normalization Plan of Hirosaki established in 2017 is the placement of a “fresh food store,” the area of which is between 1,000 and 10,000 m2, in each central district of an urban function induction area. The idea of a “city center residence” is clearly reflected in this plan. Hirosaki has put forth the idea of a “compact city + public transportation network + smart city.” Therefore, the proposal of the compact city of Hirosaki is not stronger than that of Aomori. However, Hirosaki has developed several facilities that will play a key role in solving the issue of shrinking cities. The Hirosaki City Machinaka Information Center is a symbolic facility and its location at the midpoint between the previous Hirosaki Castle site and the previous garrison of the army division is important. In the urbanization process of Hirosaki, the location of this center has connected these two cores. Hirosaki Station opened in 1927, and Chuo Hirosaki Station opened in 1952 located between these two historical cores that function as the third and fourth urban cores, respectively. Thus, these four cores form a well-balanced urban infrastructure.

As mentioned above, marked differences exist in the urbanization processes of Aomori and Hirosaki, despite similarities in population declines and economic trends between the areas. Regarding countermeasures against shrinking cities and the effects of such measures, Aomori and Hirosaki show markedly different characteristics. These differences may be the reasons for the difference in the net migration loss between the two cities.

Peripheral Small Towns of the Core Cities

Onomichi: Migration by DIY Renovation

The rate of population decline in Onomichi was higher (-5.0%) than that of municipalities in the same population category (between 80,000 and 200,000), excluding the three metropolitan areas (-2.3%). However, the contribution ratio of the net migration loss was lower than that of the natural decrease. Therefore, Onomichi has successfully kept people in the city and encouraged new residents to move into the city to a certain extent, although the population has decreased overall.

Onomichi faces the Seto Inland Sea, and its population is slightly less than 140,000. In the Edo period, because goods-carrying merchant ships stopped at a port in Onomichi, it was the most prosperous city with a commercial port in the Seto Inland Sea. From the 1980s to the 1990s, many movies were set in Onomichi, and the city became associated with several famous writers. Onomichi attracted the attention of many tourists as a city with ties to movies and literature. Recently, Onomichi has become known as a city with many hills and sloping landscapes, and consequently many cyclists have visited the Setouchi Shimanami-Kaido Expressway. Onomichi has thus become a major tourist destination in Hiroshima Prefecture. However, the population of Onomichi has shown a decreasing trend, with the population of the previous Onomichi area before its merger continuously decreasing after its peak in 1975.

In the nine-year study period (2010–2019), although the natural decrease was approximately 7%, the net migration loss was only approximately 1%. In 2016, Onomichi experienced a net migration gain, although it only amounted to 39 people. The net migration loss has continued, but the contribution ratio of the net migration loss has remained low. According to the 2015 census, the number of intra-prefectural migrants into Onomichi was smaller than that out of Onomichi by 964 (a net migration loss). However, the number of inter-prefectural migrants from other prefectures was larger than that of other prefectures by 232 (a net migration gain). In Fukuyama, which is adjacent to Onomichi, with a population of 465,000, the number of intra-prefectural migrants into Fukuyama was larger than that out of Fukuyama by 1195 (a net migration gain). However, the number of inter-prefectural migrants from other prefectures was smaller than that of other prefectures by 904 (a net migration loss). Thus, Onomichi contrasts markedly with Fukuyama. In the micro-level inter-regional competition, the number of intra-prefectural migrants of Onomichi (-964) was much worse than those of Fukuyama (-623), Hiroshima (-295), Higashihiroshima (51), and Mihara (30). However, according to the macro-level inter-regional competition from the perspective of population change, Onomichi’s performance is acceptable. In particular, the difference between the number of inter-prefectural migrants from the three metropolitan areas and the number of inter-prefectural migrants to these areas was +109 in 2010 and +114 in 2015. Therefore, unique population movements can be observed in Onomichi. The difference between the number of inter-prefectural migrants from areas aside from the three metropolitan areas and the number of inter-prefectural migrants to these areas was +311 in 2010 and +118 in 2015.

Regarding the reason for Onomichi’s unique population movements, town planning that utilizes its unusual historical and geographical characteristics can be cited, in addition to its above-mentioned strong competitiveness as a tourist destination. Onomichi is located on the graded land of the Onomichi Three Mountains. At present, this graded land, known as Yamate, is a tourist spot where only temples and shrines existed in the past. From the late Meiji period to the early Showa period (1926‒1989), business tycoons began to build villas called saen (“tea garden” in English). Since then, various types of buildings of different ages, including Western-style buildings, Japanese-style inns, and tenement houses, have been built in this area. As a result, a unique landscape peculiar to the graded land has emerged. Because Onomichi avoided strategic bombing during World War II, many 40- to 100-year-old buildings still exist in Onomichi. However, because many old buildings do not satisfy the legal obligations of road abutment, these buildings cannot be rebuilt. Because of the graded land, vehicles cannot enter this area. As a result, the renovation cost in this area is approximately three times that of flat land. Therefore, many buildings have been abandoned and left vacant. Neither the owners of these buildings nor Onomichi City Hall can do anything about this.

Recently, a non-profit organization (NPO) called the Onomichi Akiya Saisei Project (the Onomichi Vacant House Renovation Project, known as Aki-P) has engaged in active operations centering on this Yamate area. Aki-P began to renovate vacant houses in the Yamate area and approximately 20 vacant houses have now been renovated. In 2009, Onomichi entrusted Aki-P with a vacant house bank. In the eight years that followed, the bank matched approximately 80 vacant houses with new users. Consequently, the number of migrants in the Yamate area has increased. Furthermore, bakeries, cafes, and pottery forges have been opened. As a result, the Yamate area has become more attractive than ever before not only for residents, but also for tourists. Many immigrants are married couples in their 20s and 30s. Young people have migrated into the Yamate area, where the aging of the population has progressed, vacant old buildings have been repaired, and consequently, a new community has been created.

The renovation costs for vacant houses in the Yamate area are extremely high if contractors renovate these houses, as these houses are located on graded land that hampers vehicle access. However, many people have migrated to the Yamate area because they can live in individualistic and historical houses at extremely low costs, and they can perform repairs on these houses while renting them. Therefore, the majority of these immigrants renovate vacant houses by themselves (through do it yourself [DIY] renovation). Aki-P also supports these migrants. People who have already migrated and young people working at local drinking spots voluntarily help carry out household goods and garbage left in vacant houses, carry in renovation materials, and invite new migrants to move into the Yamate area. Aki-P supports migrants in various ways. For example, it holds events, such as workshops, in which migrants can learn professional skills from craftsmen, and flea markets in which household goods left in vacant house are sold. Aki-P also provides grants for repairing old houses in Onomichi to migrants.

The vacant house bank became more convenient after Aki-P took over its operation because it is open even on weekends. However, to obtain information on registered vacant houses, people must physically visit Onomichi. In many vacant house banks in other municipalities, anyone can obtain information on registered vacant houses through the internet. However, through Aki-P, the vacant house bank only introduces registered vacant houses to people who can patiently search their favorite vacant houses by themselves. Such patience is indispensable for people intending to live in Onomichi, with its many slopes and alleys. The DIY method of renovating vacant houses takes a lot of time and effort as well. Living in a place with many slopes is inconvenient, necessitating quite a bit of patience and an ability to enjoy such challenges. Aki-P provides a framework in which people can patiently perform DIY renovations while enjoying the challenge of life in an otherwise inconvenient location with the support of neighbors.

The majority of areas in which the population is declining are inconvenient places to live. To revitalize an area with a population decline, people who can acclimatize their lives to the unique conditions of the area or who truly want to live in the area should be selected, instead of a policy which accepts all comers. Aki-P has created a framework to encourage and support the lives of people who can adapt their lives to the unique conditions of Onomichi to immigrate.

Nagato: Master Plan with Private Sectors

The rate of population decline of Nagato was slightly higher (-5.0%) than that of municipalities in the same population category (between 10,000 and 50,000) (-4.9%). However, the contribution ratio of the net migration loss was lower than that of the natural decrease. Therefore, Nagato has successfully kept people in the city and encouraged people to move into the city from outside to a certain extent even though the population has decreased overall.

Nagato is located in the northern part of Yamaguchi Prefecture facing the Sea of Japan, and its population was 32,700 as of January 2020. Because Nagato lies outside of basic national traffic networks, no manufacturing industry has developed in the area. Even now, the fishing, agricultural, and stock-raising industries, their associated food processing industry, and the tourist industry are the main industries in Nagato. The population of Nagato reached its peak in 1955 (66,112) and has since continuously decreased.

Amid this state of gradual decline, Kurao Ohnishi, the former Mayor of Nagato, took office as mayor in 2011. Once instated, Ohnishi enacted a policy to increase the number of visitors, which he hoped would create jobs and stem the outflow of young people. Since then, Nagato has pursued a concept of town development that makes use of Nagato’s advantages. In 2018, the road station “Senzakitchen” was opened (The words Senzaki Port and Kitchen are combined). This road station provides fresh fish and shellfish that have been harvested at Senzaki Port as well as barbecued chicken, a local specialty. This road station has successfully attracted tourists, the number of which has been larger than predicted. Furthermore, Nagato attempted to revitalize Nagato Yumoto Onsen, a hot springs resort in Yamaguchi Prefecture located in the southern part of Nagato. Nagato Yumoto Onsen is a time-honored hot springs resort that opened in the Muromachi period (1336‒1568). In 1983, 390,000 people visited the resort. However, the number of visitors decreased to 180,000 in 2014, less than half of that at its peak. In the same year, Shirokiya Grand Hotel became bankrupt despite boasting 150 years of history and being dubbed the “hot spring of the Lord of the Mori Domain.” The massive site of the abandoned hotel provided a powerful image of decline in the form of a deteriorated hot springs resort.

In an effort to improve this situation, Ohnishi decided to purchase the land and the hotel and to dismantle the building at public expense. Ohnishi then invited Hoshino Resort, Inc., to renovate the hotel facilities. In response to the invitation, Hoshino Resort proposed a master plan through which the future of the entire area, including the hotel site, could be shared by all parties concerned; this master plan was indispensable for future organization and investment. After the renovation process began, Nagato developed this master plan together with Hoshino, which proposed the plan while the administration carried out public investment based on the plan. This was an unprecedented project. Ohnishi, the Mayor of Nagato at that time, might have had a sense of crisis about the situation of Nagato Yumoto Onsen. His sense of crisis resulted in the subtitle of the master plan: “paying attention to existing resources, and local resources led Nagato Yumoto Onsen to be revitalized (renovation of the hot-spring resort by local treasures and powers)"(). All of the parties concerned commonly understood that “this tourism town must be revitalized without compromise (Matsuoka, H., interview, March 9, 2020).” Under these circumstances, Hoshino Resort decided to invest in the unused space generated by the bankruptcy of the hotel.

In addition to creating the master plan, Nagato formed a team to promote the master plan, composed of qualified local individuals like proprietors, experts, and administrative officers. Thus, the master plan was promoted in the form of a private initiative. The promotion team commonly understood that “in the age of population decline and financial difficulties, town activation led by administrative investment without the involvement of the private sector, as in the age of economic growth, will fail, and the next generation will inherit debts” (Matsuoka, H., interview, March 9, 2020). This means that rather than seeing the revitalization efforts for Nagato Yumoto Onsen led by the local government and uninvolved citizens, local well-wishers should participate in the project as a “private business entity with a strong will to bear risks.” Due to the promotion team’s enthusiastic appeal, the previously public-operated bath was privatized. Ohnishi’s approach produced a positive result. In 2018, the number of tourists visiting Nagato reached a record high. On March 12, 2020, KAI Nagato, a new hotel was opened by Hoshino Resort on the site of the previous Shirokiya Grand Hotel, and on March 18 of the same year, Onto—a public bath reconstructed by local young businesspeople—was opened. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, KAI Nagato and Onto failed to make brilliant debuts. However, because all the parties concerned carried out their responsibilities with conviction, the local hot springs resort industry has gotten back on a path toward revitalization even while the population has continuously decreased and many businesses have disappeared.

Regarding the population decline in Nagato over this nine year period (2010–2019), the natural decrease was 11%, and the net migration loss was 3%. However, the number of people counted in the net migration loss has tended to decrease over the past five years. At the time of graduating from junior and senior high schools, some students want to leave Nagato to receive a good education. Therefore, during the graduation season, the number of people moving out is larger than that of people moving in. However, the number of people 25–29 and 30–34 years old moving in was larger than that of people moving out. This tendency has continued in recent years. Therefore, although some students move out of Nagato for better education opportunities, there are still young people who want to live in Nagato. When the results of the above-mentioned policy in Nagato are fully realized, the net migration loss will be reduced further.

Kamiyama: Promotion of Satellite Offices

The rate of population decline in Kamiyama was much higher (-13.2%) than the average among municipalities in the same population category (below 10,000) (-7.8%). However, the contribution ratio of the net migration loss was lower than that of the natural decrease. The main reason for the population decline in Kamiyama was the natural decrease. Although the net migration loss is larger than the net migration gain, the difference has been kept small.

Kamiyama in Tokushima Prefecture is a small town with a population of slightly more than 5,100. It is surrounded by mountains and filled with lush greenery but is only 30-40 minutes away from Tokushima City and one hour away from Tokushima Airport by car. Thus, Kamiyama is located in a convenient place.

The population of Kamiyama exceeded 20,000 in 1955. However, the population has continuously decreased year over year, rendering Kamiyama a so-called “depopulated town.” Recently, Kamiyama has been receiving attention as a successful example of regional revitalization due to a minor influx of migrants. Although the number of people counted as part of the net migration gain was 27 in 2011, persistent net migration loss has been observed since 2010, except for in 2011. However, more than 100 people have moved into Kamiyama every year, and young people in their 20s and 30s have accounted for approximately 50% of these new residents (51% in five-year period from 2013 to 2017). Approximately 100 people have moved into Kamiyama, with a population of around 5,000, and roughly 50% of the migrants are in their 20s and 30s. In addition, some 15 information technology (IT), design, and film-related companies have satellite offices located in the town, so Kamiyama cannot be said to be a depopulated town anymore in spite of the significant decrease of population after 1955.

Kamiyama was an exemplary depopulated town in the past, but in 1991, an International Exchange Committee was founded in the town after an old American blue-eyed doll of the type given to Japan to symbolize Japan-U.S. Friendship before World War II was found in the town. This Committee resulted in the establishment of an NPO called Green Valley. Green Valley has mainly been engaged in actions called Kamiyama projects, which invite people and companies to Kamiyama from outside. Green Valley considers that Kamiyama should aim at “creative depopulation” to change the outcome of depopulation instead of seeking a population increase. In other words, they suggest that Kamiyama should invite young people and creative human resources from outside, restore population composition, and raise the value of Kamiyama as a business area where various ways of working are possible. Consequently, Kamiyama could become a well-balanced and sustainable area without relying only on agriculture and forestry.

An artist-in-residence program that started in 1999 was the first project in Kamiyama to invite migrants. By providing accommodations and ateliers as paid services for domestic and foreign artists, the town encouraged artists to live there. Subsequently, three projects in Kamiyama launched. In the work-in-residence program, bistros, cafes, bakeries, pizzerias, shoe shops, delicatessens, and guest houses have been opened in vacant houses on shopping streets in recent years. The difference in utilization between the above-mentioned vacant houses and those located in ordinary shopping districts is that the work-in-residence program does not simply provide vacant houses for those who want to buy houses, but appoints and invites workers and entrepreneurs necessary for the future of the town. Thus, this program helps design the town. A project related to satellite offices has emphasized the extension of invitations to IT, design, and film related companies, which do not need to be picky when selecting worksites. This project has facilitated the renovation of old private houses to provide an attractive workplace environment accompanied by an older appearance and a modern interior space for young people. As part of a project of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, the Kamiyama School was opened to provide supporting training for job seekers for six months. Approximately 50% of trainees who finished the program have since immigrated into the Kamiyama Town.

As mentioned above, when artists, entrepreneurs, creators working in satellite offices, and persons who manage shops in Kamiyama migrated into Kamiyama, a new influx of people was generated and new services were created. When restaurants use agricultural products from local farmers, the economic benefits circulate within a specific area. This is Kamiyama’s regional revitalization strategy. At present, Kamiyama is planning to open a technical college using the creative human resources in the town. Therefore, a further new influx of people is expected to be generated.

Kamiyama’s efforts to invite creative human resources into the town are considered to be based on a cultural tradition of accepting the arrival of new people from outside the town, excellent accessibility from Tokushima Airport and Tokushima City, and the execution of projects by an NPO instead of the local administration. It took 13 years from a doll being sent back to the United States in 1991 to the establishment of the NPO. The people engaged in this activity shared their successful experiences little by little and expanded their fields of activity during this period of 13 years. Administrative projects must typically achieve a certain result within a short period of time, so successful experiences cannot be accumulated. If a project is performed by a private organization, however, the project can be continued for a long time. This is the reason for Kamiyama’s success. Kamiyama established standards for human resources and for what stores would be invited to put down roots in the town, instead of accepting all comers, and designed the town based on these standards. As a result, Kamiyama has attracted creative human resources for a long period of time.

Conclusion

Given that policies for helping municipalities often aim to help cope with population decline, this study focused on attempts that successfully reduced the contribution ratio of the net migration loss instead of the natural decrease by presenting the results of on-site investigations of six large and small municipalities. The natural decrease is difficult to eliminate within a short period of time. The above-mentioned municipalities were considered to have succeeded in their attempts to mitigate the population decline. While there were some municipalities whose policy results could not be extracted from rough statistical data, by analyzing the statistical figures in detail, the results of the policies could be clearly demonstrated.

When Kanazawa’s trend changed from a natural increase to a natural decrease, its net migration trend changed from a loss to a gain. As a result, Kanazawa’s population successfully increased. While making full use of the opening of Kanazawa Station on the Hokuriku Shinkansen line, Kanazawa continues to cope with issues of gentrification and the conservation of traditional town houses, which require subtle solutions. By implementing urban regeneration projects through structural as well as non-structural measures and reducing the number of people counted as the net migration loss, Fukui has eased the damage of population decline caused by the natural decrease. Although the population of Aomori is larger than that of Hirosaki, the contribution ratio of the net migration loss of Aomori is larger than that of Hirosaki, probably because the idea of a “city center residence,” which is a bottom-up approach instead of a top-down approach, functions effectively. Regarding Onomichi, although the number of people constituting the net migration loss is not very small, the number of intra-prefectural migrants was negative and the number of inter-prefectural migrants was positive. Thus, unique population dynamics were observed. This is considered to be the result of the NPO Onomichi Akiya Saisei Project functioning effectively. Regarding Nagato, the number of people counted as part of the net migration loss has decreased in recent years while the number of people between 25 and 34 years old who moved into Nagato has been larger than that who moved out of Nagato. This is thought to be due to the success of the drastic regional revitalization policy. By establishing the artist-in-residence program and renting satellite offices, Kamiyama has successfully brought in more than 100 young people every year, more than half of whom are in their 20s and 30s.

By analyzing the demographics of the six above-mentioned municipalities in detail, it was revealed that a population decline, which damages the sustainability of a region, can be avoided or eased by adopting policies that make full use of regional characteristics and pay attention to the net migration loss. For example, see young migrants compensated for the net migration loss in Nagato and inter-prefectural in-flow compensated for intra-prefectural out-flow in Onomichi. In this context, this chapter can conclude that the private sectors' initiatives and bottom-up approaches are common values for avoiding rapid population decline in these shrinking cities. The process based on bottom-up and private initiatives may be a kind of prescription for providing public value.

Table 4.2: Summary

| Municipalities | Population (2019) | Policy characteristics | Comparison of cities in the same population category | Characteristics of the net migration gain or loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hirosaki City | 284,531 | The idea of a “city center residence,” which is a bottom-up approach instead of a top-down approach. Differences in the historical urban policy between Hirosaki and Aomori. | Although the population decline rate and the contribution ratio of the net migration loss were higher than the averages, Hirosaki has done relatively well for a city in the northern part of the Tohoku region on the Sea of Japan side. | Although the rate of population decline in Hirosaki was similar to that of Aomori, the contribution ratio of the net migration loss of Hirosaki was lower than that of Aomori. |

| Kanazawa City | 453,654 | Conservation of historical town houses and attempts to cope with gentrification following the opening of Kanazawa Station on the Hokuriku Shinkansen line. | The population of Kanazawa has increased. | In 2008, the net migration loss changed to a net migration gain and the net migration gain sufficiently compensated for the natural decrease, which tended to increase. |

| Fukui City | 264,356 | Urban regeneration projects in the form of structural as well as non-structural measures. | The rate of population decline in Fukui is similar to the national average but better than that in Aomori, Akita, and Nagaoka, which are located on the Sea of Japan side. | The net migration gain compensated for the gentle natural decrease, so the population decline was eased. |

| Onomichi City | 137,643 | Attractive town development through bottom-up-type countermeasures against vacant houses. | Although the population decline rate was higher than the national average, the net migration loss was small. | The number of intra-prefectural migrants was negative, but the number of inter-prefectural migrants was positive. |

| Nagato City | 34,305 | Drastic regional revitalization policy through public and private cooperation, such as the entrustment of a private company with the creation of a master plan. | Although the population decline rate was higher than the national average, the net migration loss was small. | Recently, although the contribution ratio of the net migration loss has tended to decrease, and the population has continuously decreased, Nagato has successfully kept people in the city and encouraged people to move into the city from outside to a certain extent. |

| Kamiyama Town | 5,319 | Adoption of a policy to proactively invite people from outside. | Although the population decline rate was higher than the national average, the net migration loss was small. | More than 100 people have moved into Kamiyama every year, and young people in their 20s and 30s account for approximately 50% of this. |

Reporting Partners

- Harada, Yoko. Associate Professor, Fukui University (May 2018)

- Izumi, Hideaki. Representative Director, Heart Beat Plan Inc. (March 2020)

- Kato, Hiroshi. Director, Shopping District Promotion Cooperatives in Shinmachi Shopping Street(February 2018)

- Kawakami, Mitsuhiko. Professor Emeritus, Kanazawa University (January 2017)

- Kimura, Yoshito. Area Manager, Nagato Yumoto Onsenmachi Inc. (March 2020)

- Kitahara, Keiji. Professor, Hirosaki University (February 2018)

- Matsuoka, Yuji. Nagato City (March 2020)

- Nojima, Shinji. Professor, Fukui University (May 2018)

- Ominami, Shinya. Founding Member, NPO Green Valley (September 2016)

- Tamura, Tomiaki. Director, Economy and Tourism Department, Nagato City (March 2020)

- Toyoda, Masako and Nitta, Goro. Onomichi Akiya Saisei Project (Aki-P; September 2016 and June 2017)

Note

This chapter is an excerpt from research conducted with a grant from the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Basic Research B): “the Comparative Study on Spatial Transformation and Planning Policies of Shrinking Cities in Japan, USA, and Europe, and Suggestions” (15H04105). This was originally published in Japanese as “Research Report on Municipalities that have Mitigated Population Decline by Keeping Migratory Population Loss to its Minimum.” Reports of the City Planning Institute of Japan, 20, 27-34. May 2021.

Bibliography

- Fukui City, 2018

- Fukui City. (2018). Increase of Regional Value by Tentative Use of Vacant Parking Lots. 31st National Meeting of Parking Lots Policy.

- Kaido, 2001

- Kaidou, K. (2001). The Study of evaluation of urban-life environment by using population density indicator. Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan, 36, 421-426. https://doi.org/10.11361/journalcpij.36.421

- Kitahara, 2012

- Kitahara, K. (2012). A Sustainability of Suburban Residence in the Compact City, Journal of the Housing Research Foundation, 38, 23-34. https://doi.org/10.20803/jusokenronbun.38.0_23

- Kitou 2011

- Kitou, H. (2011). On -third of Present Population in 2100. Tokyo: Media Factory. (Written in Japanese as Jinkou Sanbunn no ichi no Nihon.)

- Mallach et al. 2017

- Mallach, A., Hasse, A., and Hattori, K. (2017). The shrinking city in comparative perspective: Contrasting dynamics and responses to urban shrinkage. Cities, 69, 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.09.008

- Martinez-Fernandeza

- Martinez-Fernandeza, C., Weyman, T. Fol, S., Audirac, I., Cunningham-Sabot, E., Wiechmann, T., and Yahagi, H. (2016). Shrinking cities in Australia, Japan, Europe and the USA: From a global process to local policy responses, Progress in Planning, 105, 1-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2014.10.001

- Nagato City, 2016

- Nagato City. (2016). Nagato Yumoto Onsen Tourism Development Plan. (Written in Japanese as Nagato Yumoto Onsen Kankou Machidukuri Keikaku.)

- Shouji, 2016

- Shouji, R. (2016). Why are compact cities failing? Yahoo! News. https://news.yahoo.co.jp/feature/423/. (Written in Japanese as Naze Compact City ha Shippai Surunoka.)

- Yokoo, 1987

- Yokoo, M. (1987). The Historical Implications of the Land Use Pattern of Hirosaki, Annals of the Tohoku Geography, 39(4), 302-315. https://doi.org/10.5190/tga1948.39.302