5. The Ecological City: With a Specific Focus on Participatory Biological Conservation

- Ryo Sakurai, Associate Professor, College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University (Japan)

The Meaning of Biodiversity Conservation in and around Cities

In order to ensure the continued well-being and longevity of human life on Earth, it is imperative and critical that the environmental issues that the world faces today be resolved. International societies have formulated and declared common goals for people to work toward to promote the creation of a sustainable society. A notable example of such goals is the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) announced by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015. The importance of conserving biodiversity is mentioned in several of the SDGs, such as Goal 14 (“Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”) and Goal 15 (“Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss”) ().

Researchers caution that planet Earth currently faces its sixth mass extinction period, as they estimate that an average of 40,000 species disappear every year (). The difference between the current phase of mass extinction and the previous ones (including the one that occurred 65 million years ago when dinosaurs went extinct), is that the current extinction is caused by one species, human beings. Wildlife habitats have been destroyed by environmental degradation, and their populations have declined due to overexploitation by humans. Biodiversity provides various indispensable services to humans, which can be categorized into those with direct value (e.g., the use of nature’s bounty for food, fuel, and medicines) and indirect value (e.g., recreational and educational). Biodiversity also plays an important role in providing ecosystem services such as climate control and nutrient cycling, and the loss of biodiversity directly threatens the sustainability of human beings' lifestyles ().

Biodiversity is not only found in remote forests or wildernesses far from cities, but also exists and flourishes in and around cities. In fact, numerous species live in and around cities and other human settlements worldwide (). For example, a study conducted in home gardens in England revealed that more than 8,000 insect species thrive within them, accounting for about a third of all insect species in the country (). Studies in Japan revealed that many wildlife species (except the endangered and threatened ones) have habitats in Satoyama (Sato means village and Yama means mountains in Japanese) and in areas in and around human settlements, including paddy and agricultural fields, streams, and village forests (). As recognized in international societies and conferences—such as the tenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP10)—cities play an important role in restoring and conserving nature and contribute to the conservation of global biodiversity (). It is for this reason that conserving biodiversity in and around cities and restoring natural expanses in residential areas have become an integral part of the process for mitigating the global biodiversity crisis confronting us today.

Ecological cities are broadly meant to promote the sustainable development of urban space (), which entails various approaches from monitoring soil and water quality, to building green roofs, to optimizing transport structures in cities (; ). In this chapter, biodiversity conservation is used as a case study to understand how the creation of ecological cities might be achieved through a participatory process.

Case Study for Conserving and Restoring Biodiversity in Residential Areas

Protecting nature in residential areas and restoring greenery in cities not only conserves biodiversity but also positively impacts people’s quality of life. Having greenery around their houses positively impacts the psychological health and well-being of residents (; ), and losing the cover of vegetation decreases their overall life satisfaction (). In addition, creating greenery or protecting nature can enhance the participatory skills and governance of the people involved if it is conducted through a bottom-up and participatory process (). Under these premises, there have been various participatory nature restoration or conservation programs implemented in and around cities worldwide.

One such project, in which the author was involved, was a participatory greening project implemented in Ushikubo Nishi District of Tsuzuki Ward in Yokohama City, Japan. Located about 30 km west of the Tokyo metropolitan area, Yokohama City is the second most populous city in the country with around 3.7 million residents (). Due to the rapid development of the city in the 1950s and an increase in population, the city lost large expanses of its natural areas (). To conserve and restore greenery, the city prepared and implemented a Green Community Development Project in which revenues from a “green tax” (taxes paid by city residents to conserve nature) were utilized. Through this project, the city facilitates community-based management and encourages residents to take the initiative to conserve and restore greenery in their neighborhoods by providing 90% of the necessary funding while the remaining 10% is paid by the districts. Ushikubo Nishi District, with 4,354 residents in 1,559 households, was used for this project and was designated one of 14 model districts in 2012; it received funding from Yokohama City for five years.

Restoring greenery and managing nature in and around residential areas cannot be done sustainably or effectively if the residents do not support or participate in such projects (). If the residents do not understand or appreciate the value of nature in their residential areas, they could be instrumental in its destruction in the process of the city’s further development; moreover, it is difficult for outsiders (e.g., other city residents, government officials, and researchers) to continually visit the area and manage such projects on behalf of the local residents. For these reasons, a community-based project is preferable to a top-down project. There are many examples of projects that fail to receive support and participation from the residents because project managers ignore the interests and motivations of the residents when trying to reach their goals ().

To understand residents' needs, concerns, and other general perceptions related to greening projects and utilize this information to improve the effectiveness of such programs, the author conducted social studies in Ushikubo Nishi District. The first step of the research was to interview members of the district committee, the “Association of Flowers and Greening.” Ushikubo Nishi District was chosen as the research site since the campus of Tokyo City University is located within the area. Furthermore, this was the only place among 14 model districts where the project was prepared and organized in collaboration with the residents and the university. Therefore, the Association of Flowers and Greening, whose primary role was to design and implement the greening project, consisted of committees comprised by residents and university faculty and graduate students.

Interviews were conducted with the seven resident committees (out of ten) and three university committees (out of six) who confirmed their ability to participate. The interviews aimed to reveal and evaluate the committees' perceptions and expectations from the project. While the details of the results of this interview are published in Sakurai et al. (), some key findings will be explained here. Regarding their expectations of the project, three resident committees mentioned that they hoped to see “more flowers and greenery” in the district, while two university committees mentioned that they expected residents would “increase their interest toward wildlife” through the project. When asked how to best achieve the goals of the greening project, two resident committees mentioned that “motivation by residents” and “interaction and communication among residents” were important, and one university and two resident committees mentioned that “outreach to residents regarding the project” would be important.

The results of a data mining analysis also revealed differences in the language used by the resident and university committees in the interviews (Table 5.1). Resident committees used words like “flower,” “kids,” and “beautiful” more often, while university committees used words like “wildlife” and “know” more frequently. The results of these interviews were later shared with committee members, which gave them the opportunity to realize the differences in perception between resident and university committees and address how to overcome such differences and collaborate more effectively ().

Table 5.1: Words frequently Mentioned by Members of “Association of Flowers and Greening” Committee in Ushikubo Nishi District (Source: revised from Sakurai et al., 2015a)

Resident Committee

| Ranking | Words | Jaccard | Frequencies | Words appeared per individual |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flower | 0.073 | 57 | 8.1 |

| 2 | Enter | 0.064 | 48 | 6.9 |

| 3 | District | 0.055 | 41 | 5.9 |

| 4 | Age | 0.046 | 36 | 5.1 |

| 5 | Make | 0.043 | 34 | 4.9 |

| 6 | Plant | 0.040 | 31 | 4.4 |

| 7 | Kids | 0.039 | 31 | 4.4 |

| 8 | Beautiful | 0.034 | 29 | 4.1 |

| 9 | Association | 0.030 | 23 | 3.3 |

| 10 | New | 0.028 | 21 | 3.0 |

University Committee

| Ranking | Words | Jaccard | Frequencies | Words appeared per individual |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wildlife | 0.139 | 31 | 10.3 |

| 2 | Greenery | 0.135 | 42 | 14.0 |

| 3 | Think | 0.134 | 46 | 6.6 |

| 4 | People | 0.128 | 39 | 13.0 |

| 5 | Plan | 0.112 | 25 | 8.3 |

| 6 | University | 0.109 | 26 | 8.7 |

| 7 | Know | 0.102 | 21 | 7.0 |

| 8 | Greening | 0.083 | 20 | 6.7 |

| 9 | Many | 0.081 | 16 | 5.3 |

| 10 | Have | 0.080 | 16 | 5.3 |

Therefore, in order to implement participatory greening projects, citizens' demands and perceptions need to be considered. A survey was conducted among the residents of Ushikubo Nishi District (a total of 810 households registered in the district’s residents' association) to understand what kind of activities were expected or desired by the residents. Two questionnaires were distributed to each household so that two family members could answer them: one who was interested in greening/planting and another who was not. After distribution of the survey in August 2013, 544 questionnaires from 274 households were returned. (The details of the results of this survey are published in and .)

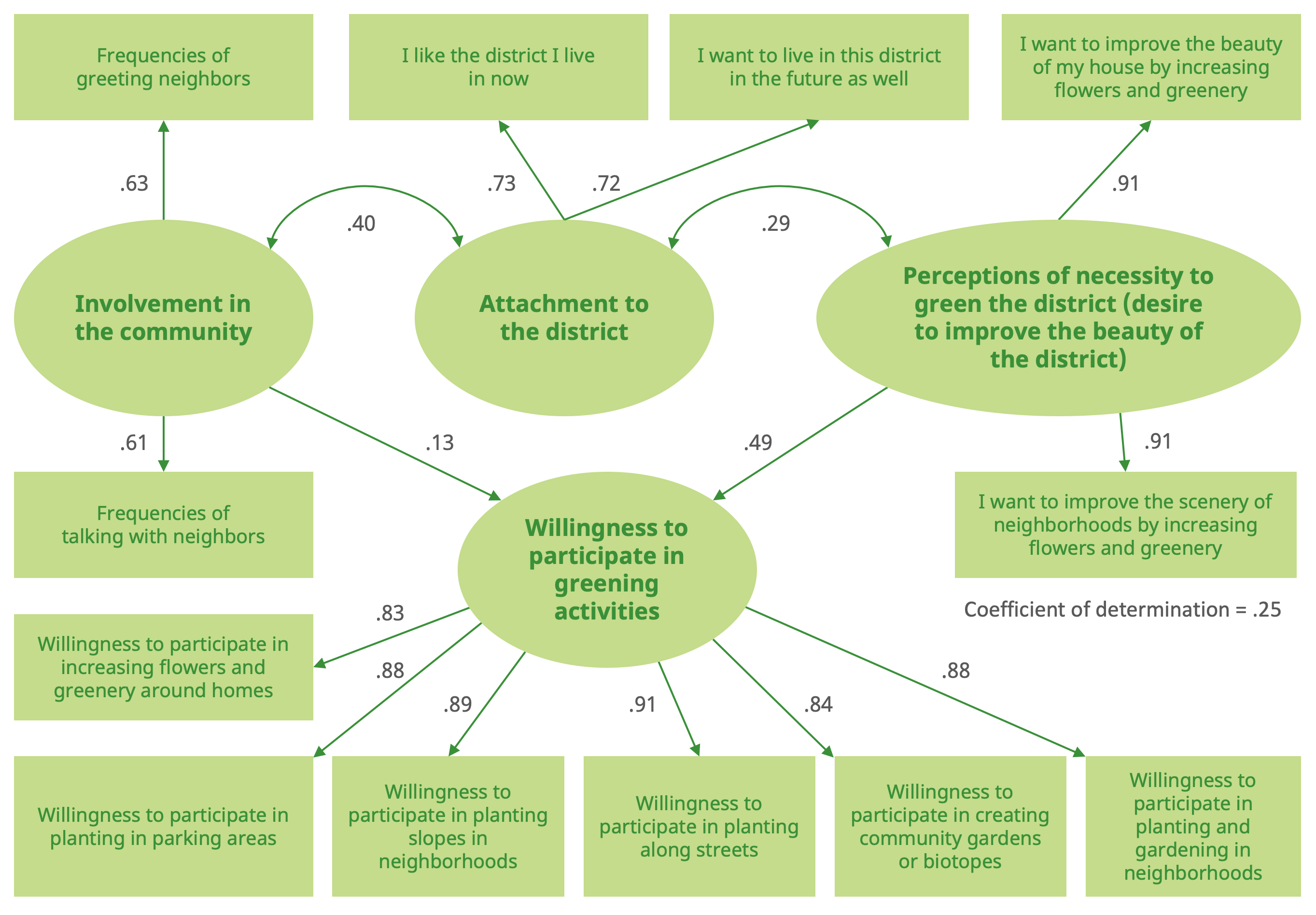

Based on a multiple regression analysis, the results revealed that the strongest factors affecting residents' willingness to participate in “creating community greenery or biotopes” and “planting along streets” were their perceptions of whether the “greening project will enhance social interaction among residents” (Table 5.2). This had a stronger effect on resident motivation than the question of whether residents enjoyed taking care of greenery. Similarly, structural equation modeling was conducted using the same data to determine the factors that affect residents' willingness to participate in greening activities. The results revealed that, in addition to residents' willingness to improve aesthetic beauty by planting flowers and greenery, their level of interaction with neighbors affected their willingness to join in the activities (Fig. 5.1).

Table 5.2: Multiple Regression Analysis with Greening Activities as Dependent Variables and Socio-Demographic and Cognitive Factors as Independent Variables. [B=standardized coefficient] (Source: )

| Creating community gardens or biotopes | B | p | VIF | R2 | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A greening project will enhance social interactions among residents | 0.245 | 0.001 | 1.351 | 0.256 | 0.241 |

| Residents should collaborate in maintaining the natural environment of the district | 0.223 | 0.003 | 1.527 | 0.256 | 0.241 |

| I take care of greenery in a garden and/or around my house | -0.202 | 0.006 | 1.434 | 0.256 | 0.241 |

| I enjoy taking care of greenery | 0.258 | 0.001 | 1.592 | 0.256 | 0.241 |

| Planting along streets | B | p | VIF | R2 | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A greening project will enhance social interactions among residents | 0.248 | <0.001 | 1.374 | 0.355 | 0.336 |

| I enjoy taking care of greenery | 0.206 | 0.004 | 1.553 | 0.355 | 0.336 |

| Taking care of greenery is troublesome | -0.166 | 0.009 | 1.226 | 0.355 | 0.336 |

| Residents should collaborate in maintaining the natural environment of the district | 0.219 | 0.002 | 1.534 | 0.355 | 0.336 |

| I know the Green Community Development Project | -0.163 | 0.007 | 1.115 | 0.355 | 0.336 |

| There are plenty of flowers in the district | -0.117 | 0.044 | 1.035 | 0.355 | 0.336 |

These analyses reveal that residents felt that the greening of residential areas was important from the perspective of enhancing community interaction. While increasing greenery and restoring nature in and around human settlements would increase the biodiversity level of the region, residents in Ushikubo Nishi District saw the project as a potentially critical opportunity to implement participatory community development. This implies that it is important for the government, researchers, and stakeholders to consider the social dimensions of creating ecological cities if they are to make such projects effective and sustainable. Since factors such as the relationship between government and researchers, government policies, and residents' perceptions of nature could be different in different countries and cultures, public interest and motivation to participate in such conservation or greening projects should be examined and understood clearly to effectively design outreach and recruit residents to participate in such activities not only in Japan but all over the world. The level of interaction and trust relationships among residents constitute “social capital,” which is defined as trusting relationships among members of a community and is comprised by social connections and shared social norms (). Understanding and improving the social capital of the community would be a key factor in enabling sustainable and effective nature conservation/restoration in urban areas.

Citizen Science and the City Nature Challenge

This section introduces an international citizen science project called the City Nature Challenge (CNC). Citizen science, defined as the engagement of the public in a scientific project (; ), has been recognized as an indispensable approach for fostering nature conservation. Citizen science advances research and science because, with the help of citizens, researchers can obtain international data within a short amount of time; data that are often impossible for most researchers to collect because of limitations in time and manpower. In addition, information on threatened species and their statuses—obtained by citizen science projects—could affect and improve policies and decision-making regarding conservation. Citizen science projects have educational effects as well, since citizens can gain a) skills to identify species and b) knowledge related to the natural environment and species by participating in various activities.

CNC is an international event in which residents observe wildlife species in and around their neighborhoods and submit photos and audio records via a mobile app. The event takes place annually from the end of April to the beginning of May. In the first half of this period, the “Observation Period,” participants submit their observations, and in the second half, the “Identification Period,” experts identify the species submitted by participants. CNC started in 2016 when the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco implemented an event where citizens in those cities came together to observe their surrounding natural environment. Year on year, the number of participants and observation sites increased, and in 2018, more than 17,000 people from 68 cities worldwide participated, observing 8,600 species in 441,000 observations (). In 2021, 53,000 participants from 419 cities in 44 countries observed 31,000 species (Fig. 5.2).

Collecting this data creates environmental education opportunities for city dwellers while providing valuable research data to identify the current biodiversity conditions in each city. It also provides the necessary data and incentives through which stakeholders are able to implement conservation and/or restoration projects. Some previous studies showed that participating in such activities not only enhanced participants' understanding and awareness of biodiversity, but also changed their behaviors (e.g., some citizens joined invasive plant removal projects and/or talked to others about invasive species after participating in citizen science activities; []). Furthermore, the spread of COVID-19 had limited effects on restraining people from observing nature because the number of participating people and cities increased even during the pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

CNCs provide opportunities for citizens to not only understand the natural environs of the city, but also to think about how nature can be conserved near human settlements. Such opportunities also provide citizens with the opportunity to connect with the nature that surrounds them (). The survey of participants in 2021 revealed that people tried to avoid crowds but still went outside to record species (), demonstrating that people remained eager to connect with nature.

While the significance of citizen science projects in terms of enhancing education, conservation, and science has been pointed out by many scholars (; ). If policy makers hope to implement effective and sustainable projects, it is important to understand what motivates residents to participate in such activities. However, few studies have been conducted to understand participants' perceptions and reactions to these international citizen science events. The author conducted a survey of CNC participants worldwide to reveal their cognitive responses to the activities in 2018. Details of the findings of this survey are published in Sakurai et al. (). Among the 361 responses that were received in this survey, 145 respondents had participated in events in the US, 113 in Japan, 34 in the UK, and 28 in Malaysia. Other respondents represented eight other countries, while some others did not specify the countries that they represented.

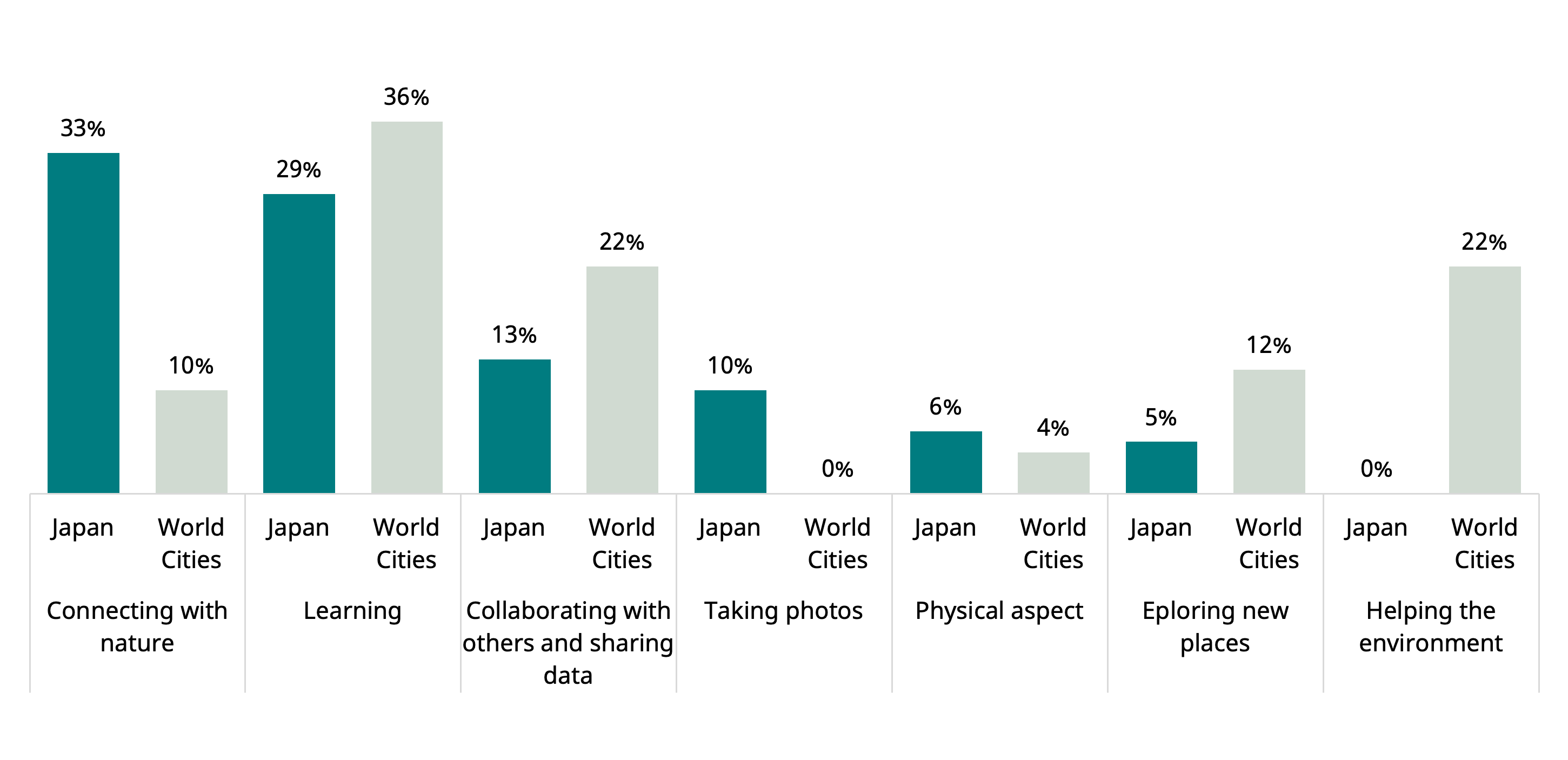

When asked about what they enjoyed the most, Japanese participants (mostly from Tokyo) mentioned connecting with nature (Fig. 5.3). While nobody in Japan mentioned saving the environment as an enjoyable factor, a fair number of global city participants raised it.

A stepwise regression analysis was conducted on American and Japanese responses to understand the factors that affect their intention to participate in similar citizen science activities in the future. The results revealed that in both countries, participants having the chance to learn about wildlife in their local areas affected their willingness to participate in future events (p<0.05) (). In other words, the more the participants learned about wildlife in their neighborhoods, the more likely they were to join future events in both the US and Japan.

Program managers could incorporate such information when tailoring their messages for participant recruitment and enhance participants' satisfaction during the activities. For example, explaining how such citizen science activities could contribute to conserving the natural environment (e.g., by providing important information on threatened species) before and during the events could raise the participants' satisfaction levels. Managers could also ensure that the participants have enough time to connect with nature (especially in countries like Japan where many people’s motivation for participation is to connect with nature) and that they learn about the wildlife in their areas, which could increase future and repeat participation. Citizen science projects would play an important role in creating ecological cities if both nature conservation authorities and the public are involved in such activities.

Sense of Place as a Potential Key Factor in Building Ecologically and Socially Vibrant Cities

This chapter shows how a participatory greening project and a worldwide citizen science project are potentially useful for creating ecological cities. While the goal of both projects is to create ecological cities by effectively conserving and restoring nature in and around cities, both cases reveal how residents value their connection to their surrounding social and natural environments. Such public attachment to a specific place or the way people confer meaning to a certain place is called “sense of place” (; ). This specific place includes both social and biological spaces, as well as both their social and cultural facets. The sense of a place is established through the actual experience of people being in that area (). The most important implication of a sense of place is that the more attachment people feel to the area, the more likely they are to take action to protect and conserve that specific area (; ).

The first example of participatory greening projects suggests how people’s sense of place, which is determined by how much time they spend in the place and interacting with their neighbors, enhances their willingness to join greening events. The CNC citizen science project increased participants' connections to their natural environment, and their learning about neighborhood wildlife encouraged them to participate in future events. By developing relationships with the natural environment existing around their neighborhoods, they became more aware of and cautious about such places. These factors seemed to enhance their attachment to places, including both biological and social environments. Studying people’s sense of place in more detail and providing more concrete data on this concept could reveal more about the indissoluble link between the social and the natural environments.

If planners only look at the ecological aspects and concentrate on restoring nature and increasing diversity while ignoring residents' perceptions and concerns, such projects will not be effective or sustainable. Similarly, we cannot create a sustainable city if we are only concerned about the social aspects, ignore the species that live around the city, and destroy nature. To create cities that are not only ecologically friendly but also socially vibrant with active interaction both among residents and between residents and their natural surroundings, it is important to understand residents' sense of place and how such place attachments can be nurtured in cities.

Acknowledgments

The second section of this chapter “A Case Study for Conserving and Restoring Biodiversity in Residential Areas” is written based on the results of three studies that were published in Sakurai et al. (; , and ), and I would like to thank the coauthors of those papers: Hiromi Kobori, Masako Nakamura, and Takahiro Kikuchi. The third section of this chapter “Citizen Science and the City Nature Challenge” is written based on the results of the study that was published in Sakurai et al. (), and I would like to thank the coauthors of this paper: Hiromi Kobori, Dai Togane, Lila Higgins, Alison Young, Keidai Kishimoto, Gaia Agnello, Simone Cutajar, and Young-sik Ham. In particular, I would like to thank Hiromi Kobori (Professor Emeritus at Tokyo City University) for inviting me to review the Ushikubo Nishi District and CNC projects, and for helping me conduct the research.

Bibliography

- Ardoin, 2014

- Ardoin, N. M. (2014). Exploring Sense of Place and Environmental Behavior at an Ecoregional Scale in Three Sites. Human Ecology, 42(3), 425–441.

- Bonney et al., 2015

- Bonney, R., Phillips, T. B., Ballard, H. L., & Enck, J. W. (2015). Can Citizen Science Enhance Public Understanding of Science? Public Understanding of Science, 25(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662515607406

- Campbell & Wiesen, 2009

- Campbell, L., & Wiesen, A. (Eds.). (2009). Restorative Commons: Creating Health and Well-being through Urban Landscapes. USDA Forest Service.

- Chen et al., 2020

- Chen, Y., Zhu, M., Lu, J., Zhou, Q., & Ma, W. (2020). Evaluation of Ecological City and Analysis of Obstacle Factors Under the Background of High-Quality Development: Taking Cities in the Yellow River Basin as Examples. Ecological Indicators, 118, 106771.

- CNC 2021

- City Nature Challenge (CNC). (2021). City Nature Challenge. Retrieved July 13, 2021, from https://citynaturechallenge.org/

- City of Yokohama, 2014

- City of Yokohama. (2014). Population News No. 1050 (February 1, 2014). Retrieved February 18, 2014, from <http://www.city.yokohama.lg.jp/ex/stat/jinko/news-e.html> (in Japanese).

- Dickinson & Bonney, 2012

- Dickinson, J. L, & Bonney, R. (Eds.). (2012). Citizen Science: Public participation in Environmental Research. Cornell University Press.

- Hill, 2008

- Hill, C.M. (2008). Working with Communities to Achieve Conservation Goals. In M. J. Manfredo, J. J. Vaske, P. J. Brown, D. J. Decker, E. A. Duke (Eds.), Wildlife and Society: The Science of Human Dimensions (pp. 117–1280). Island Press.

- Jordan et al., 2011

- Jordan, R. C., Gray, S. A., Howe, D. V., Brooks, W. R., & Ehrenfeld, J. G. (2011). Knowledge Gain and Behavioral Change in Citizen Science Programs. Conservation Biology, 25(6), 1148–1154.

- Jorgensen & Stedman, 2001

- Jorgensen, B. S., & Stedman, R. C. (2001). Sense of Place as an Attitude: Lakeshore Owners' Attitudes Toward their Properties. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21, 233–248.

- Kishimoto & Kobori, 2020

- Kishimoto, K., & Kobori, H. (2021). COVID-19 Pandemic Drives Changes in Participation in Citizen Science Project “City Nature Challenge” in Tokyo. Biological Conservation, 255, 109001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109001

- Kobori et al., 2016

- Kobori, H., Dickinson, J. L., Washitani, I., Sakurai, R., Amano, T., Komatsu, N., Kitamura, W., Takagawa, S., Koyama, K., Ogawara, T., & Miller-Rushing, A. J. (2016). Citizen Science: A New Approach to Advance Ecology, Education, and Conservation. Ecological Research, 31(1), 1–19.

- Krasny, 2020

- Krasny, M. E. (2020). Advancing Environmental Education Practice. Cornell University Press.

- Krasny et al., 2014

- Krasny, M.E., Russ, A., Tidball, K.G., & Elmqvist, T. (2014). Civic Ecology Practices: Participatory Approaches to Generating and Measuring Ecosystem Services in Cities. Ecosystem Services, 7, 177–186.

- Miller & Spoolman, 2016

- Miller, G. T., & Spoolman. S. E. (2015). Living in the Environment (18th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Ministry of the Environment, 2001

- Ministry of the Environment. (2001). Research and Analysis of Satochi Satoyama in Japan (mid-term report). (In Japanese). Retrieved September 7, 2021, from http://www.env.go.jp/nature/satoyama/satoyamachousa.html

- Oke et al., 2021

- Oke, C., Bekessy, S. A., Frantzeskaki, N., Bush, J., Fitzsimouns, J. A., Garrard, G. E., Grenfell, M., Harrison, L., Hartigan, M., Callow, D., Cotter, B., & Gawler, S. (2021). Cities Should Respond to the Biodiversity Extinction Crisis. Urban Sustainability 1(1),1–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-020-00010-w.

- Owen, 2010

- Owen, J. (2010). Wildlife of a Garden: A thirty-year Study. Royal Horticultural Society.

- Primack & Kobori, 2008

- Primack, R. B., & Kobori, H. (2008). Introduction to Conservation Biology. Interdisciplinary approach for biological conservation (2nd Ed.). Tokyo: Bun-ichi Sogo Shuppan. (in Japanese).

- Sakurai et al., 2015a

- Sakurai, R., Kobori, H., Kikuchi, T., & Nakamura, M. (2015a). Opinion gaps and Consensus Building Between Members of the Association for Community Development Embracing Flowers and Greenery Based on their Positions: From Qualitative and Quantitative Studies. People and Environment 41(1), 40–47.

- Sakurai et al., 2015b

- Sakurai, R., Kobori, H., Nakamura, M., & Kikuchi, T. (2015b). Factors Influencing Public Participation in Conservation Activities in Urban Areas: A Case Study in Yokohama, Japan. Biological Conservation, 184, 424–430.

- Sakurai et al., 2016

- Sakurai, R., Kobori, H., Nakamura, M., & Kikuchi, T. (2016). Influence of Residents' Social Interactions in and Affections Toward their Community on their Willingness to Participate in Greening Activities. Environmental Science, 29(3),137–146. (in Japanese with English abstract).

- Sakurai et al., 2022

- Sakurai, R., Kobori, H., Togane, D., Higgins, L., Young, A., Kishimoto, K., Agnello, G., Cutajar, S., & Ham, Y. (2022). A case study from the City Nature Challenge 2018: international comparison of participants' responses to citizen science in action. Biodiversity. Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2022.2054860

- Stedman, 2002

- Stedman, R. C. (2002). Toward a Social Psychology of Place: Predicting Behaviors from Place-based Cognition, Attitude, and Identity. Environment and Behavior, 34, 561–581.

- Tan et al., 2017

- Tan, G. C. I., Lee, J. C., Chang, T., & Kim, C. (2017). 3: Four Asian Tigers. In A. Russ, & M. E Krasny. (Eds.), Urban Environmental Education Review (pp. 31–38). Cornell University Press.

- United Nations, 2021

- United Nations. (2021). The 17 Goals. Retrieved October 4, 2021, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Van et al., 2019

- Van, S., Cheremisin, A., Glinushkiin, A., Krasnoshchekov, V., Davydov, R., & Yushkova, V. (2019). Application of new Architectural and Planning Solutions to Create an Ecological City (on the Example of Shanghai, China). In E3S Web of Conferences, 140, 09008. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/201914009008.

- Yokohama Environmental Planning Bureau, 2013

- Yokohama Environmental Planning Bureau (2013). Yokohama Green-Up Plan. City of Yokohama: Yokohama (in Japanese).

- Youngentob & Hostetler, 2005

- Youngentob, K., & Hostetler, M. (2005). Is a New Urban Development Model Building Greener Communities? Environmental Behavior, 37, 731–759.