6. Building an Inclusive City

- Ari-Veikko Anttiroiko, Adjunct Professor, Tampere University (Finland)

Introduction

Living in a society implies that we are conditioned by various kinds of situational, traditional, and institutional in/out or on/off “relays” that determine our social statuses and relations with other people, groups, and organizations. Such social relays serve both exclusionary and inclusionary purposes. The uses of these mechanisms have evolved over time, with the major transformation taking place in the transition from the customs and hierarchical rules of tribal, agrarian, and imperial societies to the complex institutional matrix of durable institutions in functionally differentiated late modern societies. In this latter context, practically all exclusionary practices have been exposed to ideology critique and moral evaluation. Many activities that used to be seen to reflect a legitimate group-based exclusion are today condemned as prejudicial practices or discrimination. In short, it is widely agreed that developed countries have become more open, inclusive, and democratic than what they were in pre-modern times (). Inclusiveness is, indeed, a critical element of social development, and, as concluded by Estivill (), the transition towards an inclusive society has become a prevailing trend throughout the world. That said, developed countries may not be as inclusive as commonly believed. This urges us to take a closer look at exclusion and consider possible opportunities to make improvements in terms of social, political, and economic inclusion.

This article discusses the localization of the inclusion agenda and asks: on what kind of framework should urban communities in the developed world build their inclusion policies? This chapter is based on a realist, domain-specific universalism, which is reflected in an emphasis on common humanity and harmony among people living in an urban community. In addition, this discussion is oriented toward improving people’s chances to participate in value creation to benefit themselves as well as the surrounding community, which is an under-researched topic in urban and community research (; ) as well as in other branches and subfields of social sciences (; ; ). This implies a shift in concern from social to economic inclusion or, in other words, from entitlement to value creation. Such an approach is expected to catalyze economic inclusion and lead to the improvement of quality of life among all segments and sectors of the community.

Remarks on Exclusion

Discussion about inclusion can begin with a discussion of exclusion because inclusion is supposed to intervene in a social setting in which some unnecessary, unjustified, or immoral exclusionary mechanisms are in place (). It is necessary to point out that exclusion, despite its negative connotation, has been and still is a natural and even necessary feature of social life. Exclusionary rules or actions define boundaries between “us” and “them” when governing social interaction, determining people’s positions in local decision making, controlling borders, proving ownership of a property, organizing family life, and keeping communities safe (). Let us consider such instances as identities based on kinship, marriage or citizenship, activities such as business transaction, military service, or a football game, or organizations such as hospital, school, or convenience store, which all exclude and include people in one way or another—based on assent, submission, birth, payment, special requirement, role-playing, and so forth—vis-à-vis the given social spaces, institutions, and activities even in open and democratic societies (e.g., ; ; ).

However, there are instances in which exclusion is not based on a legitimate function or tradition but appears to be unnecessary, unfair, harmful, unjustified, or immoral. This is the essence of exclusion that is referred to in the global inclusion agenda. For example, the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs states that “social exclusion describes a state in which individuals are unable to participate fully in economic, social, political and cultural life, as well as the process leading to and sustaining such a state” (). This statement refers to societal conditions in which some people are unjustly prevented from participating in mainstream society.

Even if both justified forms and subjective views of exclusion relativize the inclusion agenda, it is ultimately based on observations on the existence of the forms of exclusion that reflect sexism, racism, religious discrimination, classism, ageism, discrimination against obese people, or ableism in working life, the subtle acts of unjustified exclusion in everyday life, or complex processes relating to unemployment, attainment gaps, or problems with substance abuse, which eventually exclude people from mainstream society. Even if society per se is hardly the sole reason behind individual hardships in an open and democratic society, there is an ethically grounded obligation to develop inclusive structures and practices that are conducive to enhancing quality of life in the population at large.

The Emergence and Mainstreaming of the Global Inclusion Agenda

Social inclusion as it is commonly understood today evolved through small steps during the development of civilizations rooted in the European cultural heritage and the Enlightenment in particular (; ; ). While the eighteenth-century Enlightenment itself was rather Eurocentric in many respects and can be seen to reflect white supremacy to a degree (), it nevertheless enriched the ideas of individual freedom and equality and challenged the conventional justifications for colonialism (see ; ). Even if nation-building processes of the modern era contained some inherent exclusionary elements, radical shifts pushed development towards inclusion especially after the revolutions of 1848, as evidenced by demands for more citizen participation and greater freedom of the press, the lifting of restrictions on political assembly, the improvements in working conditions and the respect for labor rights, the introduction of national social insurance schemes, and the introduction of women’s universal suffrage and their right to stand for election ().

The first half of the 20th century witnessed a gradual weakening of colonialism, the rise of communism and fascism, and the eruption of two world wars. World War II was a watershed in the ideological landscape, marked by a considerable weakening of conservative ethnocentrism due to its war-related legitimation crises, while at the other side of the ideological spectrum the rise of Soviet-led Eastern Bloc, radical countercultures, social movements, left-wing politics, and the building of the welfare state increased the prominence of collectivist thinking. A left-leaning cultural semi-revolution in the late 1960s evoked a persuasive identity struggle reminiscent of the century-old Marxist idea of class struggle, which legitimized attacks against market economies, institutions, authorities, and belief systems that were the building blocks of modern societies (). Such fundamental ideological and structural elements of Western civilization were seen to represent the interests of the white supremacist capitalist elite, and thus to serve inherently exclusionary functions built for safeguarding its material interests. Radical movements directed attention to marginalized people’s ability to participate effectively in economic, social, political, and cultural life—this effectively stretched the scope of the concept of exclusion to cover practically any kind of subjective alienation and distance from mainstream society (). This view has been instrumental in the gradual mainstreaming of the progressive inclusion agenda.

Western democracies began to address social and economic exclusion on a larger scale during the 1980s and 1990s. One of the starting points for the institutional promotion of social integration and inclusivity was the World Summit for Social Development held in Copenhagen in 1995. This idea gained significant ideological and institutional support from international organizations, such as the OECD, the IMF, and the World Bank, and regional organizations, the most influential among them being the European Union (; ). They contributed to the creation of high-level inclusion agenda, which indirectly affected the integration of inclusion into national and local policy agendas (). Similar developments are evident in the mainstreaming of DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) in the corporate world and in the wide range of inclusion-oriented activities conducted by civil society organizations at different institutional levels.

From Particularism to Holistic Inclusion

As mentioned earlier, a critical historical turn took place after the World War II due to the retreat of ethnocentrism and nationalism as a reaction to their association with the absurd violence of the two world wars (cf. ). The subsequent moral confusion that emerged created a fertile breeding ground for radicalism and progressivism that in the 1960s boosted the wave of movements fighting against drastic injustices and demanding equal opportunity, especially for women, workers, racial minorities, and the poor (; ).

The turn from the demands for equality of opportunity in the 1960s to the entitlement thinking of the 1990s and the following decades depicts a dramatic change in identity politics. The radicalized identity politics started to essentialize identity, rendering its relationship with inclusion somewhat problematic (cf. ). Mainstream politics were challenged by two camps of essentialist identity politics in particular, those of right-wing populism, which represents ethnocentric, reactionary, localist, and revanchist responses to global solidarity, “uncontrolled” migration, and a democratic deficit, and left-wing identitarianism, which is associated with a heterogenous group of radical, anarchist, and progressive forces with particularistic agendas, while at the same time being united against their arch-enemy, portrayed as a white supremacist heteronormative capitalist patriarchy (on identity politics, see ; ).

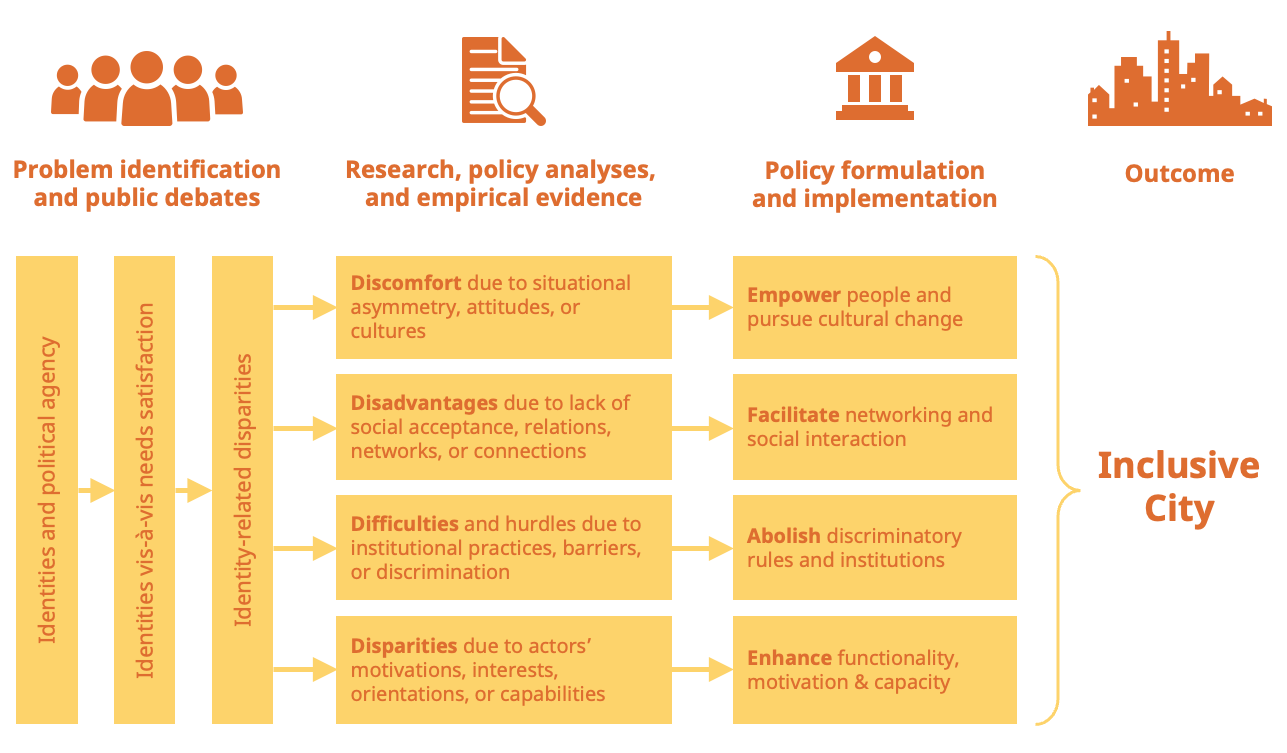

Various identity groups play a positive role in public policy by pinpointing the forms of exclusion in society based on their experiences and their views of historical, structural, and/or cultural aspects of exclusion (). However, problems arise when identity politics radicalizes and becomes openly divisive, antagonistic, essentialist, and particularistic. Such “common enemy politics” relies as a rule on misconstrued epistemology and social ontology (; ; ; ; ). It attributes a priori practically all barriers to need satisfaction as well as all observed socio-economic disparities to structural discrimination, which builds a shaky epistemic ground for inclusion (see, e.g., ; ). On top of this, the salience of identities in politics tend to increase their manipulation for political gains (). Therefore, understanding the role of identities in local policymaking calls for unbiased, empirically grounded policy research and analysis—and ultimately de-essentialization of identity categories—as the epistemic precondition for a sound policy (on empirical analysis of social exclusion, see e.g. ; ). This is particularly important because inclusion policy hardly ever addresses only disadvantaged groups but involves also other actors in the given asymmetric or discriminatory setting. This highlights the role of relationality, which entails, due to its implicit boundary conditions, situational ambiguities, and changing subject positions, that inclusion must be seen ultimately partial by necessity (cf. ). The articulation of this through three main categories—identities, disparities, and policies—and four schematic action categories is illustrated in Fig. 6.1.

It is noteworthy that inclusion programs and trainings tend to increase divisiveness and even inject toxicity in workplaces, as claimed by Chloé Valdary (), which may be the case with local communities as well. The message to city governments is that they should refrain from becoming handling centers for sectional interests and particularistic policy demands (). Another problem with essentialist identity positions among separate groups is their tendency to feed a victim mentality (), which in turn fuels antagonism and leads to the articulation of social problems in the way that makes them look unsolvable.

There is a risk that raw emotions overtake politics and, further, that victimhood anchors emotional guidance to resentment and hatred rather than to compassion and forgiveness (cf. ). Emotional dimensions play a role (especially at an individual level) in laying a moral foundation for an inclusive city—most notably in the context of a multicultural and racially divided society (see ; ). It has its pitfalls too, however, as pointed out above. Heightened emotion may exacerbate political polarization and even lead to a politics of demonization (see ).

A true policy challenge lies in understanding how the problems identified with exclusion should be articulated and addressed at the institutional level within the local policymaking process. At this level, local government should show place-based leadership as a balancing and unifying force that acknowledges equivocality, democratic dialogue, a search for common ground, the importance of a shared common vision, and strategic actions that reflect the compassionate “common humanity politics” (cf. ; ; ). Open and democratic local institutions contribute to the local political culture of inclusion, which is a critical piece of the puzzle, as variations in local political culture explain to some extent the differences in the patterns of relationships between identity variables and political outcomes ().

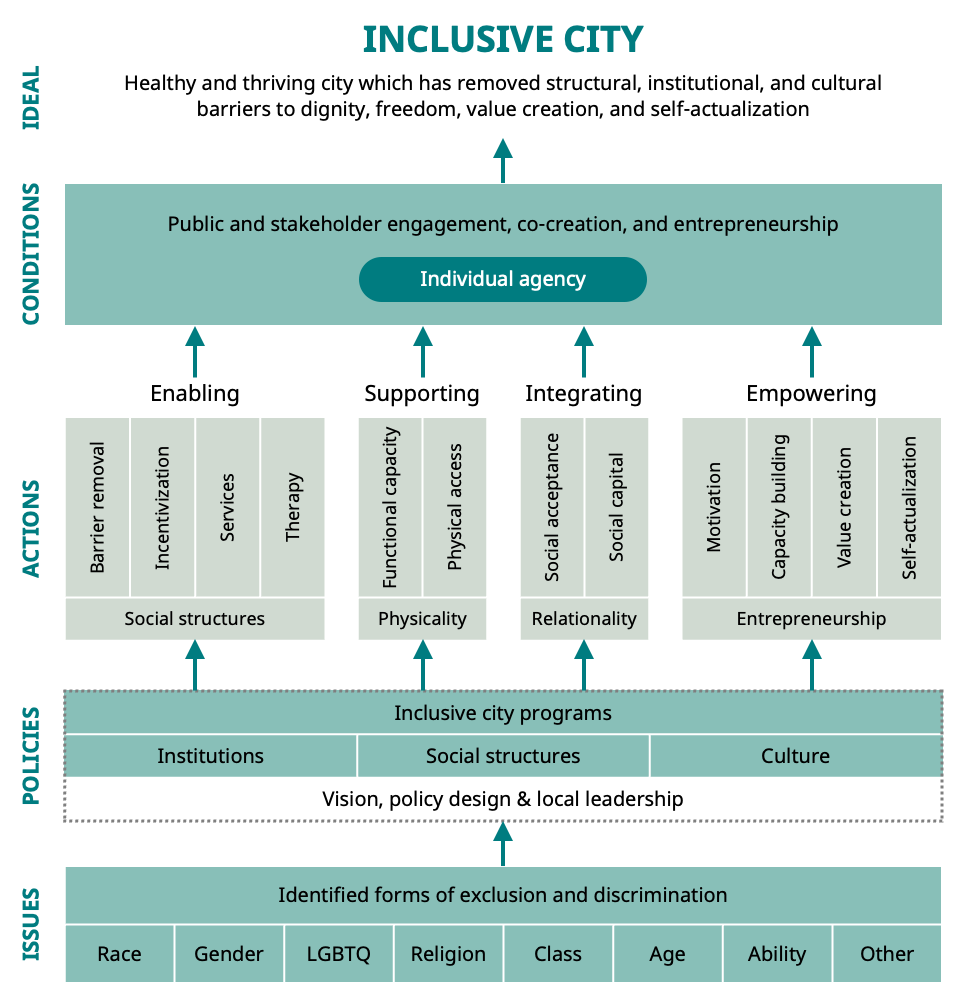

A Framework for Urban Inclusion

Pathological forms of exclusion have historical precedents in dynastic elitism, caste systems, apartheid systems, and legal discrimination against ethnic minorities. Such cases represent the systemic and institutional exclusion of certain groups from the mainstream society. Modern Western societies have abolished such systems altogether, even though some existing disparities can be assumed to persist as a reflection of the injustices and discriminatory practices of the past. Developed countries enacted laws during the post-war decades to make discrimination illegal, which is a significant step forward. Moreover, many public and private institutions have included inclusion in their operational principles, values, or brand attributes. Consequently, in advanced democratic societies the major problem is not large-scale discriminatory behavior as such but the culture that may underpin some subtle exclusionary elements or produce cognitive biases that lead to the underutilization of people’s capacities. The message to local governments is clear: they should put structures in place to support, enable, integrate, and empower those who are not able to participate fully in mainstream society.

Hilary Silver () emphasizes that social inclusion has two sides: inclusion in social interaction and inclusion in institutional environments that open access to participation in various spheres of social life. According to her, social inclusion is “a multi-dimensional, relational process of increasing opportunities for social participation, enhancing capabilities to fulfill normatively prescribed social roles, broadening social ties of respect and recognition, and at the collective level, enhancing social bonds, cohesion, integration, or solidarity.” The UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs emphasizes similar elements in its definition, even if its emphasis is explicitly on participation of disadvantaged groups: “social inclusion is defined as the process of improving the terms of participation in society for people who are disadvantaged on the basis of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, or economic or other status, through enhanced opportunities, access to resources, voice and respect for rights.” ().

Inclusion is in essence an intervention into an extremely complex societal setting comprised by interrelated factors. The building of an inclusive city is a holistic endeavor that cannot be managed by the city government alone. A move towards an inclusive city is possible only if the institutional stakeholders and community members in different roles internalize the idea of inclusion and practice it in their everyday lives. This means that actions should be taken to implement inclusivity in underlying cultures, social structures, and institutional practices. It is important to seek common denominators of inclusion, which are the building blocks of the vision of the city, inclusive policy design, and inclusion-oriented local leadership (e.g., ). If the political leaders and public managers adopt an inclusive, empowering, and democratic leadership style, it promotes inclusion throughout the municipal organization and extends an influence through numerous actors and various channels into the local community, eventually reshaping local culture.

A precondition for successful holistic interventions is to approach inclusion as a multi-layered phenomenon. Regarding physically disadvantaged groups, Schleien et al. () state that the concept of inclusion may be best viewed as a continuum that includes three levels of acceptance:

-

Physical integration. At this level an individual’s right to access is recognized.

-

Functional inclusion. This refers to an individual’s ability to function successfully within a given environment.

-

Social inclusion. This refers to person’s ability to gain social acceptance and/or participate in positive interactions with friends and peers during recreation, hobbies, and other leisure activities.

In the case of marginalized identity groups, measures designed for them may include the following categories of policy intervention: (a) anti-oppression psychotherapy and counselling; (b) improving motivation, awareness, self-esteem, and opportunity enhancement; (c) capacity-building and the provision of support services to create preconditions for functional capacity and individual or collective performance; (d) incentivization and nudging that fosters inclusive mindsets and behavior changes; (e) barrier removal and institutional finetuning to guarantee equal access, fairness, and equality of opportunity across the institutional landscape; (f) group-specific inclusion programs or affirmative actions designed under carefully scrutinized case-specific conditions; and (g) supporting participation in value-creation processes and entrepreneurship (cf. ).

The key elements of inclusive city policymaking are illustrated in Fig. 6.2.

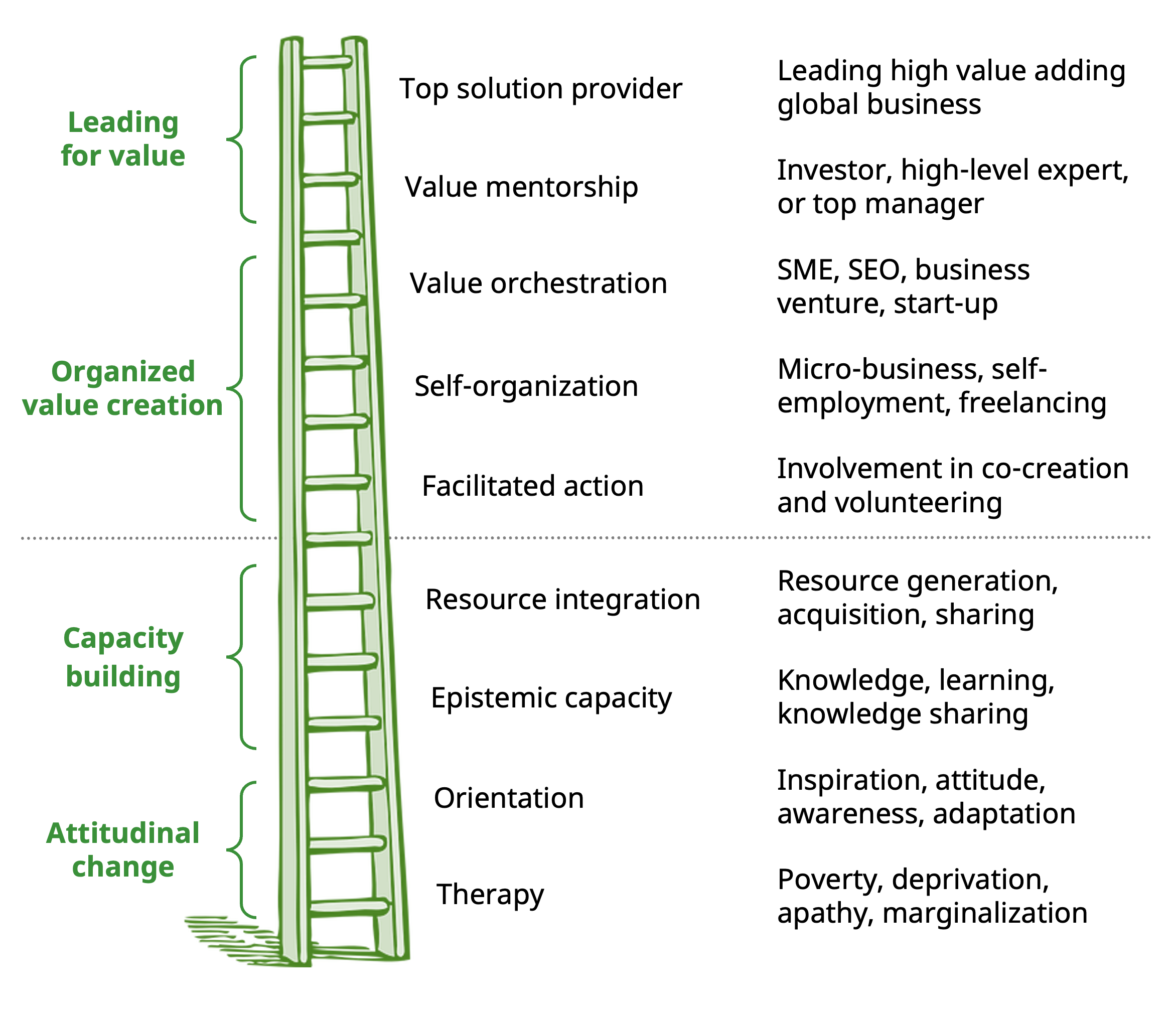

Promoting Value Creation through Inclusion

One of the aims of this chapter is to highlight the need to focus on economic integration, which may facilitate holistic inclusion in a more constructive way than what we might call the “victim-centered” and “rights-based” approaches. While a victim-centered approach is a must in traumatic and criminal processes, and rights-based approach has its place in addressing grave human rights violations, they are not conducive when coaching people in strengthening their human capacity, contributing to co-creation within a local association, becoming a member of local cooperative, or starting a small business. Such processes require a value creation approach, which in a democratic society urges us to redirect attention from human rights to people’s ability to use their competencies and resources to generate something of value that is sold to a customer base, offered as publicly subsidized service, or provided for free to those in need. It is an effective way of integrating people into society through a simultaneous promotion of awareness, identity-building, capacity-building, relational capital, empowerment, and material reward. Following this logic, the classic models and typologies of citizen participation can be changed into a model of value creation, as illustrated in Fig. 6.3.

Practically all holistic inclusion schemes attend to people’s stakes, contributions, and other aspects of value creation. For example, O’Brian’s () five accomplishments that support valued experience and build community competence include the following: growing in relationships, contributing, making choices, having the dignity of valued social roles, and sharing ordinary places and activities. This list is based on a thorough understanding of the needs of disabled people, and the consideration of how human service programs should be designed to contribute to this target group’s lives. “Contributing” points to the need to allocate resources to assist people with disabilities in discovering and expressing their gifts and capacities. Everyone has some capacity to contribute to their local community, and when society is able to utilize such a capacity it can integrate people in a meaningful way and eventually provide them with a source of greater self-control, happiness, and meaning (cf. ; ; ).

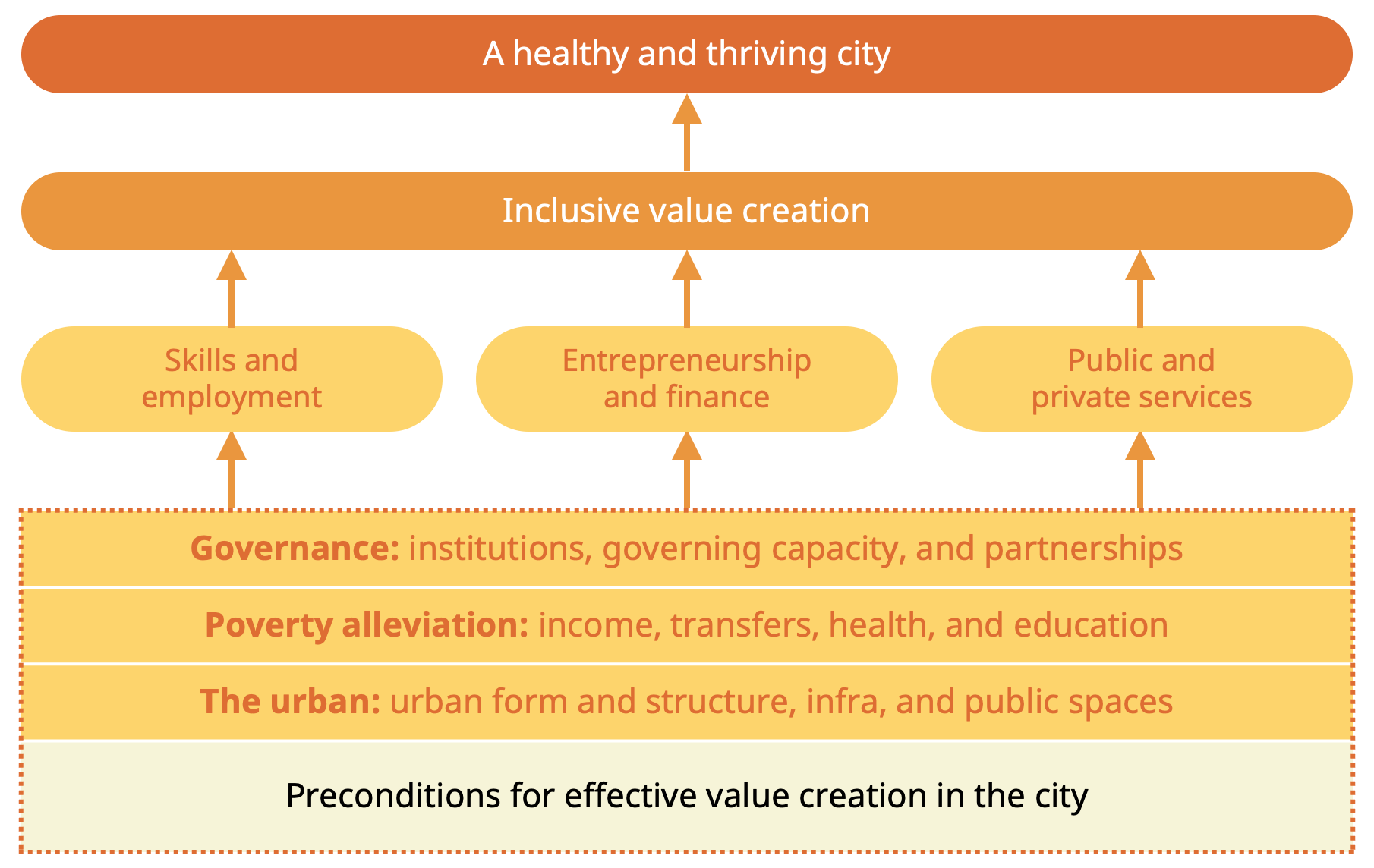

The construction of an inclusive city must have a foundation in the local institutional and cultural setting. Therefore, the precondition for building an inclusive city is poverty alleviation, inclusive infrastructures, and the provision of a supportive institutional framework. When targeted initiatives for supporting, enabling, integrating, and empowering people are introduced with the support of physical, institutional, and social infrastructures, they have better chances to bring about sustainable results. Finally, the strategic actions that support urban value creation can be grouped into three core areas: (a) access to skills and employment; (b) entrepreneurship and access to finance; and (c) access to services that enhance economic opportunities (EBRD, 2017). These three points form the operational core of the support for local value creation, and this core can be extended to a broader set of grassroots-level value enhancement practices that harness diverse capitals and potentials from people and communities for the purposes of value creation. Ultimately, inclusive policy should create an environment that is conducive to entrepreneurship () and to the creation of an inclusive capitalism ()—this is illustrated in Fig. 6.4.

The above model is a conceptual scheme that highlights the most vital elements of urban economic inclusion policy. Specific actions depend on the situation and features of each community, which may vary from cities operating within a welfare-society framework, to those affected by municipalism or progressive movements, to ones that are undergoing profound industrial restructuring (). Approaches that exemplify citizen-centric economic inclusion include self-employment and working-class entrepreneurialism (), microbusiness, family business, and home-based business (), popular economy (), social and solidarity economy (), and a range of special forms of entrepreneurship, such as senior, youth, academic, women, LGBTQ+, social, green, minority, ethnic, indigenous, immigrant, informal, prison, and disability entrepreneurship (; ). All of these incorporate entrepreneurship into various domains of community life in their own ways. Such approaches serve as bridges between social and economic spheres of urban life and form an important supplementary side of urban economic inclusion.

Conclusion

Building an inclusive city is a surprisingly complicated process, demanding thorough conceptualization of the theoretical premises of such an endeavor, the anticipation of trade-offs between different groups demanding inclusion, and a recognition of the challenges of creating unity and harmony at the local level. The above discussion points out that exclusion and inclusion are complex, multi-dimensional, and relational phenomena that call for smart policy responses. First, in such a sensitive and knotty area as exclusion/inclusion, epistemic accuracy and sophistication are a necessary precondition for sound policy. Second, as inclusion as a phenomenon is complex, so too must the policy be complex; as such, one useful simplifying scheme would be to divide actions into four categories—i.e., supporting, enabling, integrating, and empowering—each responding to a particular form of exclusion. Lastly, rather than antagonism and divisiveness, policies should reflect holism, unity, and compassion in order to create a genuinely constructive and inclusive atmosphere.

This chapter has argued for the critical role of economic inclusion, as it is supposed to serve as a catalyst for holistic integration due to its natural tendency to inspire, empower, and bring together city dwellers and other local stakeholders. The aim of this policy is the creation of an inclusive city that is not only open, democratic, and fair but also entrepreneurial and economically thriving. Such a city would aim to promote the idea of a shared prosperity, which by cultivating co-creation and other ensuing processes would contribute to the pursuit of meaningfulness and happiness in the lives of city dwellers.

Bibliography

- Acs & Stough, 2008

- Acs, Z.J., & Stough, R.R. (Eds.) (2008). Public Policy in an Entrepreneurial Economy: Creating the Conditions for Business Growth. Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-72663-2

- Allman, 2013

- Allman, D. (2013). The Sociology of Social Inclusion. SAGE Open, 3(1), 1-16. DOI: 10.1177/2158244012471957

- Anttiroiko, 2019

- Anttiroiko, A.-V. (2019). Paradoxes of Identity Politics and Gender Mainstreaming: The Case of Nordic Countries. The International Journal of Policy Studies, 10(1), 151-160.

- Anttiroiko & de Jong, 2020

- Anttiroiko, A.-V., & de Jong, M. (2020). The inclusive city: The theory and practice of creating shared urban prosperity. Palgrave Pivot.

- Bar-Tal et al., 2009

- Bar-Tal, D., Chernyak-Hai, L., Schori, N., & Gundar, A. (2009). A sense of self-perceived collective victimhood in intractable conflicts International Review of the Red Cross, 91(874), 229-258. DOI:10.1017/S1816383109990221

- Birelma, 2019

- Birelma, A. (2019). Working-class entrepreneurialism: Perceptions, aspirations, and experiences of petty entrepreneurship among male manual workers in Turkey. New Perspectives on Turkey, 61, 45-70. DOI:10.1017/npt.2019.18

- Bleich & Morgan, 2019

- Bleich, E., & Morgan, K.J. (2019). Leveraging identities: the strategic manipulation of social hierarchies for political gain. Theory and Society, 48, 511-534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-019-09355-3

- Carey & Festa, 2009

- Carey, D., & Festa, L. (Eds.) (2009). The Postcolonial Enlightenment: Eighteenth-Century Colonialism and Postcolonial Theory. Oxford University Press.

- Cederberg & Villares-Varela, 2019

- Cederberg, M., & Villares-Varela, M. (2019). Ethnic entrepreneurship and the question of agency: the role of different forms of capital, and the relevance of social class. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(1), 115-132. DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1459521

- Cheung et al., 2014

- Cheung, T.T.L., Gillebaart, M., Kroese, F., & De Ridder, D. (2014). Why are people with high self-control happier? The effect of trait self-control on happiness as mediated by regulatory focus. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, article 722. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00722

- Cooney, 2021

- Cooney, T.M. (2021). The Palgrave Handbook of Minority Entrepreneurship. Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66603-3

- de Jong, 2021

- de Jong, M. (2021). Inclusive capitalism. Global Public Policy and Governance, 1, 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43508-021-00020-z

- Deci & Ryan, 2000

- Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (2000). The "What" and "Why" of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268. DOI: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Deleon & Naff, 2004

- Deleon, R.E., & Naff, K.C. (2004). Identity Politics and Local Political Culture: Some Comparative Results from the Social Capital Benchmark Survey. Urban Affairs Review, 39(6), 689-719. DOI:10.1177/1078087404264215

- Dobusch, 2021

- Dobusch, L. (2021). The inclusivity of inclusion approaches: A relational perspective on inclusion and exclusion in organizations. Gender, Work and Organization, 28(1), 379-396. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12574

- Duffy, 1995

- Duffy, K. (1995). Social Exclusion and Human Dignity in Europe. Background Report for the Proposed Initiative by the Council of Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Espino, 2015

- Espino, N.A. (2015). Building the Inclusive City: Theory and Practice for confronting urban segregation. Routledge.

- Estivill, 2003

- Estivill, J. (2003). Concepts and strategies for combatting social exclusion: An overview. Geneva: International Labor Office – STEP/Portugal.

- Flanagan, 2021

- Flanagan, T. (2021). Progressive Identity Politics: The New Gnosticism. C2C Journal, July 9, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021, from https://c2cjournal.ca/2021/07/progressive-identity-politics-the-new-gnosticism/?fbclid=IwAR3tHtD1uu8vX2nCiOeHZnf67iZ60Mo_40GGC4b-Gijb7eCmy-jusVAd6Qk

- Freter, 2018

- Freter, B. (2018). White Supremacy in Eurowestern Epistemologies: On the West’s responsibility for its philosophical heritage. Synthesis Philosophica, 33(1), 237-249. DOI: 10.21464/sp33115

- Furedi, 2017

- Furedi, F. (2017). The hidden history of identity politics. Spiked, December 1, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2021, from https://www.spiked-online.com/2017/12/01/the-hidden-history-of-identity-politics/

- Furedi, 2019

- Furedi, F. (2019). A perpetual war of identities. Spiked, 1st March 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2020, from https://www.spiked-online.com/2019/03/01/a-perpetual-war-of-identities/

- Gago, 2018

- Gago, V. (2018). What are popular economies? Some reflections from Argentina. Radical Philosophy, 2(02), 31-38. Retrieved October 1, 2021, from https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/what-are-popular-economies

- Good Gingrich & Lightman, 2015

- Good Gingrich, L., & Lightman, N. (2015). The Empirical Measurement of a Theoretical Concept: Tracing Social Exclusion among Racial Minority and Migrant Groups in Canada. Social Inclusion, 3(4), 98-111. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v3i4.144

- Haidt, 2017

- Haidt, J. (2017). The Age of Outrage: What the current political climate is doing to our country and our universities. City Journal, December 17, 2017. Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. Retrieved July 11, 2020, from https://www.city-journal.org/html/age-outrage-15608.html

- Hambleton, 2015

- Hambleton, R. (2015). Leading the inclusive city: Place-based innovation for a bounded planet. Policy Press.

- Heyes, 2020

- Heyes, C. (2020). Identity Politics. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.), *The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy *(Fall 2020 Edition). Retrieved September 24, 2021, from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/identity-politics/

- Hornung et al., 2019

- Hornung, J., Bandelow, N.C., & Vogeler, C.S. (2019). Social identities in the policy process. Policy Sciences, 52, 211-231. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9340-6

- Houston & Reuschke, 2017

- Houston, D., & Reuschke, D. (2017). City economies and microbusiness growth. Urban studies, 54(14), 3199-3217. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016680520

- Kohn & Reddy, 2017

- Kohn, M., & Reddy, K. (2017). Colonialism. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 Edition). Retrieved May 11, 2022, from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/colonialism/

- Loktieva, 2016

- Loktieva, I. (2016). Approaches to Empirical Analysis of Social Exclusion: International Comparison. Economics and Sociology, 9(2), 148-157. DOI: 10.14254/2071-789X.2016/9-2/10

- Lukianoff & Haidt, 2018

- Lukianoff, G., & Haidt, J. (2018). The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. Penguin Press.

- Mascareño & Carvajal, 2015

- Mascareño, A., & Carvajal, F. (2015). The different faces of inclusion and exclusion. CEPAL Review, 116, 127-141. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18356/00b3dff6-en

- McCloskey, 2019

- McCloskey, D. (2019). Why liberalism works: How true liberal values produce a freer, more equal, prosperous world for all. Yale University Press.

- McWhorter, 2021

- McWhorter, J. (2021). Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America. New York: Portfolio/Penguin.

- Mendell, 2014

- Mendell, M. (2014). Improving Social Inclusion at the Local Level Through the Social Economy: Designing an Enabling Policy Framework. OECD. Retrieved September 25, 2021, from https://www.oecd.org/employment/leed/Improving-Social-Inclusion-Capacity.pdf

- Monroe et al., 2000

- Monroe, K.R., Hankin, J., & Bukovchik Van Vechtenm, R. (2000). The Psychological Foundations of Identity Politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 419-447.

- Moran, 2020

- Moran, M. (2020). (Un)troubling identity politics: A cultural materialist intervention. European Journal of Social Theory, 23(2), 258-277. DOI:10.1177/1368431018819722

- Murie & Musterd, 2004

- Murie, A., & Musterd, S. (2004). Social Exclusion and Opportunity Structures in European Cities and Neighbourhoods. Urban Studies, 41(8), 1441-1459. DOI: 10.1080/0042098042000226948

- O’Brian, 1989

- O’Brian, J. (1989). What’s Worth Working For? Leadership for Better Quality Human Services. Responsive Systems Associates. Retrieved September 18, 2021, from https://thechp.syr.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/whatsw.pdf

- Pinker, 2018

- Pinker, S. (2018). Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. Penguin Random House. Viking.

- Rawal, 2008

- Rawal, N. (2008). Social Inclusion and Exclusion: A Review. Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 2, 161-180. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/dsaj.v2i0.1362

- Schleien et al. 2003

- Schleien, S., Green, F., & Stone, C. (2003). Making Friends Within Inclusive Community Recreation Programs. American Journal of Recreation Therapy, 2(1), 7-16.

- Sen, 2000

- Sen, A. (2000). Social exclusion: Concept, application, and scrutiny. Social Development Papers No. 1. Manila: Asian Development Bank. Retrieved May 11, 2022, from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/29778/social-exclusion.pdf

- Short, 2021

- Short, J.R. (2021). Social Inclusion in Cities. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 3, article 684572. DOI: 10.3389/frsc.2021.684572.

- Silver, 2015

- Silver, H. (2015). The Contexts of Social Inclusion. DESA Working Paper No. 144. October 2015. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. United Nations.

- Sowell, 2019

- Sowell, T. (2019). Discrimination and Disparities. Revised and Enlarged Edition. Basic Books.

- Taylor, 2006

- Taylor, J. (2006). The Emotional Contradictions of Identity Politics: A Case Study of a Failed Human Relations Commission*. Sociological Perspectives*, *49*(2), 217-237. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2006.49.2.217

- UN DESA, 2016

- UN DESA (2016). Leaving no one behind: the imperative of inclusive development. Retrieved September 18, 2021, from https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/rwss/2016/full-report.pdf

- Valdary, 2019

- Valdary, C. (2019). Reconciliation, or Grievance? Modern diversity training too often violates Martin Luther King’s vision of racial healing. City Journal, June 6, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2021, from https://www.city-journal.org/diversity-training?wallit_nosession=1

- Valdary, 2021

- Valdary, C. (2021). Black People Are Far More Powerful Than Critical Race Theory Preaches. Newsweek, May 10, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021, from https://www.newsweek.com/black-people-are-far-more-powerful-critical-race-theory-preaches-opinion-1589671

- Ward & King, 2017

- Ward, S.J., & King, L.A. (2017). Work and the good life: How work contributes to meaning in life. Research in Organizational Behavior, 37, 59-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2017.10.001

- Zafirovski, 2011

- Zafirovski, M. (2011). The Enlightenment and Its Effects on Modern Society. Springer.